Zlatko Paković, the director of Srebrenica. When we murdered rise, on his artistic process, Ibsen, Brecht, and the relationship between institutions and the imagination.

Darija Davidovic: What does theater mean to you and what function should theater have in society?

Zlatko Paković: The more courageously I got to know myself, the closer I came to theater. The more I deal with theater, the better I shape myself. The more I am interested in the well-being of society and its change, the more I am attached to theater.

Theater is a conceptual game that can – paradoxically in vitro in vivo – fundamentally change reality. This imaginary change in the specific conditions of the play, with living and active people on stage and in the audience, inevitably arouses the suspicion and retaliation of conservative opinion and those in power.

Therefore, it is a risky concept, a risky game to reshape oneself and the society. This is the point at which a profession becomes a life’s work. So, to stage Shakespeare’s Hamlet; is not only to show others the moral achievement of this brave man, but to empower oneself for the same experience.

DD: You were born and raised in socialist Yugoslavia, you went to school there, studied in Yugoslavia, participated in cultural life. How has Yugoslavian culture influenced your work as an artist (or does it still influence it)?

ZP: The Yugoslav culture – hence the Yugoslav socialist culture! – is the base of my self-governance, opinion and work. First of all, it is built on the concept of world literature and world conscience. And not on the grotesque substitute concept of national literature and national conscience! Yugoslav socialist culture participated in world processes, with the claim to shape the world history.

Secondly, the Yugoslav socialist culture with its idea and practice of self-government is the only one in Europe based on the ancient Greek concept of democracy as direct democracy and on atheism as the inviolable right of free thinking and uncompromising unveiling and criticism of any dogmatism. Yugoslav socialist culture represents anticlericalism, antinationalism and anti-capitalism in practice. This culture is demonstrably anti-fascist and anti-Stalinist. And thirdly, this culture has acquired in its native Serbo-Croatian language a unique experience, by European standards, of speaking the truth through works of art inspired by Orthodox, Catholic and Islamic theology. Therefore, I am a Yugoslav artist, both in Belgrade and in Zagreb, Tuzla and Subotica, Zenica and Zadar, Bitola and Pristina, Podgorica and Novi Pazar.

DD: During the 1990s, you worked as a theater director in Cyprus and Bulgaria. Was this the starting point of your work as a theater director? Why did you return to Serbia and how did the experience in Cyprus and Bulgaria influenced your work in Serbia?

ZP: After my directing studies, those were the first years of independent practical learning in theatrical institutions. I also managed to produce a controversial play, based on Georg Tabori’s farce Mein Kampf, which was performed for a short time in the Zad kanala(Off the Channel) theater in Sofia. But I also managed to create an undoubted hit, also in Sofia, in the Theater 199, namely Arthur Miller’s tragicomedy I can’t remember anything, which featured the most popular actors. This play packed the venues for a whole decade, until the death of the famous Georgi Rusev, who acted in both of the above-mentioned plays and who was my friend. My words are quoted on the cover of his memoir, published at the end of the last century.

In the theater of the Bulgarian city of Montana, where only one of the 25 actors remained during the capitalist transition, I staged the play The Second Wednesday; based on Margarit Minkova’s work. At that time, working on this play gave me a completely new experience. In this huge, empty theater, working on its large stage with one actor and three singers of folk songs, using an iron fire curtain and opening a large door to bring in the décor, to enclose the outside, a part of the city itself – this suddenly felt as if I were not in an institutional theater, but in my own institution, which I was allowed to use according to my own principles.

Within this and such a kind of freedom of exploring, without the compulsion to succeed, as in the laboratory, the elements of the method that I am still developing today, have emerged very strongly. This production, which few people saw, was the most beautiful desert rose. At that time, I managed to involve the audience into the happening, so that they not only witnessed the awakening of one of their fellow citizens after ten years in a coma, who now finds himself in completely changed social circumstances, but also the audience itself, on stage, could finally touch its own social life, finally see it clearly and see it as a monster.

It was then that I realized that directing means, above all, orchestrating the reception, directing spectators’ attention, composing their emotions, and guiding the audience through the process of their reasoning. It was then that I irrefutably understood that the institutions of theater restrain, restrict, and, of course, try to strictly discipline the imagination by rewarding you with success and creating the illusion that you have just expressed yourself as an author.

It took me a long time to find the conditions for working beyond the institutional setting, which is one of the main characteristics of my directing. Theater is a matter of radical imagination. Theatrical institutions and radical imagination are mutually exclusive. So, when I work in an institutional context, in one of the national theaters, first of all I work on building an environment that contradicts the principles of the institution. In other words, I don’t talk about the play until I form an ensemble through improvisations. Necessarily, their work becomes the basis of my work and my work becomes the necessary basis for their work. Thus, solidarity is established as the sine qua non of the theatrical process, of collective artistic creation. After all, what is theater but an invitation to the spectator to show solidarity with the dramatic hero and heroine who dare to act morally, despite the consequences they will suffer on account of it?

I returned to Belgrade from Bulgaria to work on the first independent television production VIN – Video Weekly on an enormous social task of overturning Slobodan Milošević and his clique. This work taught me cautious responsibility.

In editing, you can arrange any material to say what you want, even if it is completely at odds with the intentions of the interlocutors and the event itself. But it is up to you to take responsibility, to work in the interest of what is called objective truth. Your task is to give a mirror of social reality. This is the directing and acting task of which Hamlet speaks. Theater is a radical imagination, it means the right to radically change reality, but what is reality? We are obliged to represent it as if in a mirror. And what does that actually mean? The mirror of the play should also reflect what is hidden from the public in reality and what exactly determines reality.

Srebrenica. When we murdered rise

DD: Your plays are very political and socially critical. What are the central themes of your work?

ZP: Let’s start with Ibsen’s Enemy of the People; as with Brecht’;s Teaching Play! it is a play about the power of theater in relation to the violence of reality. But when we talk about the power of theater to expose the lies on which a regime is based, we must be aware of the corruption susceptibility of theater to work in the service of this lie on which a regime is based. Brecht himself condemned theatrical illusionism as an internalized violence of reality over imagination. Therefore, by exposing theatrical illusionism, we reveal the mechanism of social illusionism. But theater professionals are mostly opportunists. Genuine Promethean personalities are rare among them.

Let’s see what Ibsen tells us about that! His hero, Dr. Stockmann, a spa doctor, decided to tell the truth about the fact that the water in the spa is polluted and that he actually poisons his patients while treating them. The whole town has now conspired against him because, frankly, he is threatening spa tourism with losses instead of profits. Stockmann, however, insists on telling the truth. He will lose his job over this. His daughter will also lose her job because of it. His son will be kicked out of school for it. The fate that awaits Dr. Stockmann is actually the fate of truth. If he does not unite with other free personalities, if he is left alone, Dr. Stockmann will be destroyed. This is what Ibsen shows us.

Brecht speaks of this in his plays. However, what happens when there are no other free people in Stockmann’s city to ally with? We find the answer in Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound. It’s about the most beautiful happy ending in the history of drama. Happiness in tragedy! Prometheus accepts suffering and enjoys the freedom to defy Zeus and call him a good-for-nothing! Betrayal of truth is the greatest disease, says Prometheus. He is responsible for the truth, but not for the suffering it causes him. Today generations are educated in such a way that they are blamed for the suffering if they tell the truth. It is the education in obedience. Against this, there is much dramatic literature and theater as education of resistance.

From Aeschylus to the present day, the task of playwrights and directors in their Promethean vocation is to encourage themselves and others to live radical heroic lives that defy the arrogant gods.

DD: In Srebrenica. When we murdered rise you deal with the responsibility of the Serbian cultural and intellectual elite for the genocide. The necessity and priority to deal with this topic as an artist (especially in Serbia) is obvious. But why in 2020? Were there any particular reasons why you started to deal with the Genocide 25 years afterwards?

ZP: I tried to carry out this play a few years before its premiere in 2020. No theater institution wanted to deal with this issue. Moreover, they refused to show the already finished production. The fact that it was realized on the 25th anniversary of the genocide is due to the conditions at that time. The only organization in Serbia which was and still is willing to produce this play, although it has never produced a play before, is the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia.

DD: You and your ensemble were exposed to public threats and insults. How did this kind of violence affect your work?

ZP: The play was created in two phases. In 2019, I staged a lecture-performance in Kolarac (Endowment), in which I presented all the materials and motifs of the play. At that time, the audience had the opportunity to see all the preliminary work for the creation of a work of art, as in a studio. However, during this lecture, about thirty supporters of Ratko Mladić shouted in the hall. They tried to stop the lecture for half an hour, but they only managed to interrupt it, not to stop it. Thus, they themselves became an integral part of the lecture-performance. Reality simply entered the symbolic order of the performance. At the same time, both in reality and in imagination, it became an open conflict between those who support the perpetrators of genocide and those who speak for those who were murdered. Symbolically, the genocide was repeated that night.

A year later, I directed the play. Threats followed, a mass of horrible messages, anonymously and openly, two charges and numerous instigations of violence in the obscure media. However, worse, more dangerous and more tragic than these threats are the silence of the theater and other cultural institutions, the silence of prominent bourgeois intellectuals who raise their voices only when they do not get the expected leadership position or money from cultural funds. Silence means lying. Silence means complicity with murderers. My play supposes this.

DD: Srebrenica. When we murdered rise is a complex play. It contains quotes from historical figures, allusions to the current Serbian cultural elite, allusions to Serbian theater during the 1990s, songs with political content, references to other politically motivated crimes, the fictional Bećković family as another narrative layer, through which you create a kind of psychogram of the Serbian elite. You yourself appear as a narrator, but also as director. In addition, you criticize the political instrumentalization of the genocide commemoration in Bosnia and Herzegovina in some scenes. How did you combine all these motives and topics?

ZP: I only stage plays for which I have been preparing myself for many years and whose topics I consider to be part of my personal obligation to speak about them in public. Then it is my task to talk about it as accurately and comprehensively as possible and, above all, to understand the crux of the problem and to point its causes. For me, it is unworthy of a theater invitation to talk about the current state of affairs. I always point out the cause of the situation and possibility or at least the necessity of its change.

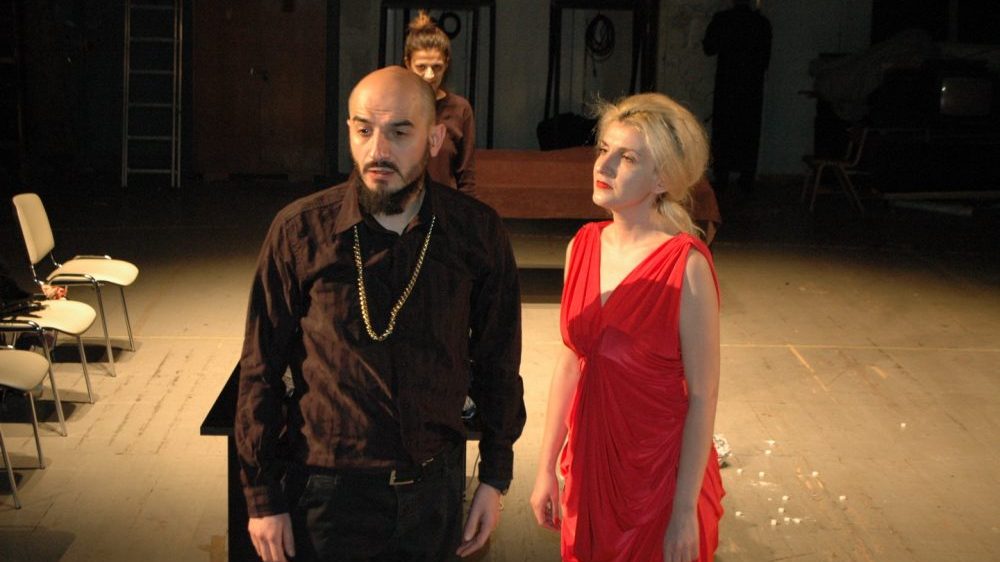

Zlatko Paković’s Srebrenica. When We, the Murdered, Rise Up

DD: Srebrenica. When we the murdered rise seems to be a play that works less through emotion, empathy and identification, but rather through intellectual stimuli. Why did you choose this approach to convey the subject of genocide on stage?

ZP: Unexpectedly, in this play about the genocide, there are no depictions of the crimes, which is also in line with the concept and idea of the play. Why should I show the crimes when the play does not talk about the perpetrators of the crime as the main perpetrators of the genocide, but it turns out that the intellectuals as the inspirers of the genocide are the main perpetrators. Everything in the play takes place, as in reality, in a bourgeois atmosphere, in offices and lavish mansions, in the midst of the so-called fine world, which, over coffee or tea, whiskey or schnapps, discusses the realization of nationalist dreams, the redrawing of state borders, ethnic cleansing, territorial exchanges and humanitarian resettlements. These intellectual dominions shoot with fiery words which turn into deadly ammunition on the field. Their hands remain clean, but their language is bloodier than the hands of murderers. Without them, there is no concept of genocide.

DD: Music seems to be an important element in Srebrenica. When we murdered rise, but also in many other of your plays, such as your last play Ako dugo gledaš u ponor, for which you received the Sterijino pozorje award. What is the function of music in your productions?

ZP: The passage of music or song enters the stage at that moment, when words, whether because of the tragic moment, must pass from horror to silence and to the ceremony of remembrance of the victims, or where, in excitement, the moment of epiphany is accentuated, a great erotic moment. At the end of last year, I directed Shakespeare’s Hamlet without music, but I achieved musical moments. How? I insisted on a tempo furioso of the acting, to make the audience think quickly, because Hamlet has to think quickly.

Facts of experience appear in front of him again and again, therefore he has to create the overall picture, without which he cannot act. Then I connected the scenes in such a way that the previous one did not end when the following one already began. This is how I achieved syncopation. This intrinsically musical form emerged from an understanding of the substance of the piece. Here I can practically confirm Hegel’s insight that form is substance, which means that a piece of art implies the identity of substance and form. I can also confirm John Cage’s experiment, because in my play Hamlet; every piece of music is determined by silence as well as by tension before the string is struck. In this example I show what music means in a play and to what extent it was composed by a composer.

Ako dugo gledaš u ponor

DD: Henrik Ibsen and Bertolt Brecht seem to be important for your work. Why them and how are they suited to each other? How do you use the work of these great playwrights for your own ones?

ZP: Besides the easily recognizable dramaturgical differences, there are significant similarities between Henrik Ibsen’s and Bertolt Brecht’s involvement with theater, namely in introspection and aspiration.

This is best seen by comparing the plays Rosmersholm by Ibsen and Mr Puntila and his Man Matti by Brecht. In Rosmersholm, a representative of the upper class falls in love with a woman of the lower class. This love fills him so much that it changes him fundamentally. He becomes a humanist and a socialist. This upsets his family and his social environment. As time goes by, under the influence of his environment, he reverts to his old ideas of private property, class divisions, even the superiority of the upper class, and becomes incapable of love. In Brecht, Mr. Puntila is a humanist, socialist, compassionate, sociable, generous, cheerful and full of love when he is drunk and out of his mind, and when he is sober, he becomes a stubborn landowner, a capitalist and cutthroat who wants to profit from every relationship and who subjugates everyone.

The transformation that Ibsen’s hero undergoes through love is in Brecht’s play realized through comedy and intoxication. In any case, the point is that human beings are derailed from the world of being into the world of existence in order to become a person of their own life. Both Brecht and Ibsen are aware that freedom begins where possession ends. Both of them tell us about the forgotten power of ideals. About the fact that humans consist primarily of their ideals, not of identities.

Identities are armaments. And every identity can be integrated. Ideals create this non- integrating part, which in reality is resistant. An integrative non-integrating part. That’s how you become a human being. That’s how catharsis is achieved. That’s what I’m going to discuss in the piece about Pasolini that I’m working on at the moment.

DD: What are you working on next?

ZP: These are the titles of four pieces I will be making in four cities over the coming year. Pedagogy of Resistance by Branko Ćopić, PierPaolo Pasolini directs the Last Judgement, The Tomb of Boris Davidović 2022 and Katalin Ladik suffers a nervous breakdown, quits her job as a bank employee and becomes a conceptual artist.

Dr. Darija Davidović is based in Bern, Switzerland and Vienna, Austria. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the research project “Aestheticisation of war violence in contemporary performing Arts” at the Institute of Practices and Theories in the Arts, Bern Academy of the Arts. She obtained her doctoral degree from the University of Vienna, Department of Theatre, Film and Media Studies with her theses “Contested Wartime Past(s): practicing politics of history in Serbian and Croatian Contemporary Theater”, which will be published in 2024. She has been involved as activist in many feminist and antifascist projects and campaigns in Germany and Austria.