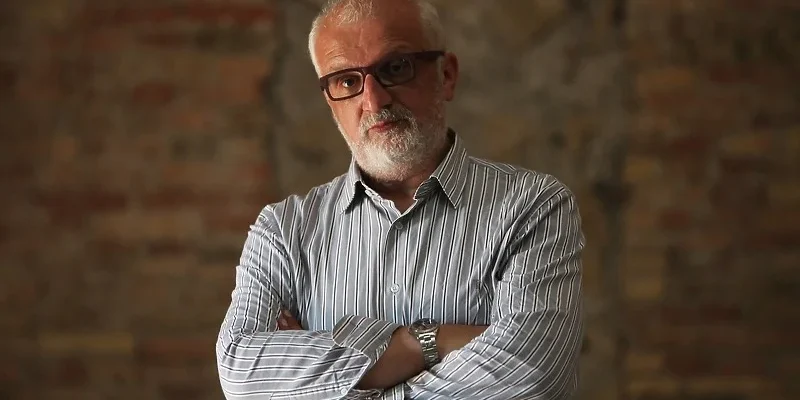

Haris Pašović’s new show World of Possibilities depicts the everyday lives of disabled people, their families and carers. The director talks to Nick Awde about his methodology and wider questions of inclusion, representation and artistic responsibility.

Bosnian director Haris Pašović has an ongoing mission to highlight social issues through the lens of theatre. His most recent show, World of Possibilities (Svet mogućnosti), a devised work that, through a series of vignettes, opens a window into the everyday lives of people with disabilities, focusing on the experience of people with autism and cerebral palsy.

Central to the Sarajevo-based director’s methodology is research, and a show typically arrives before the public only after months of R&D by the team and direct contact with people and communities. Since this is mainstage work that won’t get made on inspiration alone, in World of Possibilities’ case it was Creative Europe that opened up the possibility to do the groundwork for the Enabled Theatre project with support from four Balkan cultural organisations who also co-produced.

Pašović worked on the project with the cast and creative team for more than a year on and off. While the onstage musician Matija Molčanov has autism, the actors are all non-disabled and carefully enact the physical aspects of each character’s disabilities in a script where the dialogue is informed by their conversations with disabled people and their families, carers and therapists. Crucially these are based on local experiences based in Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia, reflecting three of the production partners: Budva’s JU Theatre City, Novi Sad’s Serbian National Theatre (where the play premiered in April 2024), Sarajevo’s East-West Centre and Zagreb’s Dance Centre Tala.

The partner institutions do not usually platform disabled creativity. So the obvious question is whether depiction of disabled people by non-disabled actors is ‘cripping up’ – a term used to describe the playing of disabled characters by non-disabled performers – or a necessary first step within the context of a region where there is scarce visibility or representation. Is World of Possibilities actively making disabled people more visible? Does it open the door for disabled creatives to follow and share their lived experiences in front of the same audiences? And to express their creativity with equity, not just their ‘stories/voices’ but as a Hamlet or a Hedda Gabler?

Part of the answer lies in the evident depth of the R&D that the show’s team has undertaken with disabled people and their families as well as occupational therapists and psychologists in Novi Sad, Budva and Sarajevo. Specialists in institutions are as relevant in some ways as individuals with lived experience because they are testament to the history of a region where disability did not form a part of everyday life but was considered a stigma and confined behind closed doors with no thought for inclusion – an attitude that hasn’t wholly disappeared.

World of Possibilities, Serbian National Theatre

“We learned all this slowly, step by step,” says Pasovic. “And in narrowing down our research to people with autism and cerebral palsy, we started to focus on people who cannot live independently. We had to learn how to ask questions like what are the barriers they face, what are their successes, and then we looked at the different levels of progress made or not made in the different countries they live in.

“We went to places like the Milan Petrović school and centre in Novi Sad, which were built up from zero to hero because when they started 40 years ago there was almost nothing to provide for disabled people and, thanks to specialists like the school’s director, psychologist Slavica Marković, they have changed political and social perceptions. But the work we did in direct contact with people with disabilities was obviously the most important element and also the most emotional. I think the show is worthy not only because of the resonance of disability for society but also because we didn’t want to present only a basic sketch of their experience. We wanted to understand this world as far as we could and to work out how to share with an audience the challenges that they face on a daily basis.”

With these bases covered, a script emerged and when rehearsals started in February 2024, the ensemble was clear about the scope and aim of the show. “We had explored all the possibilities with the people we were consulting to see whether we could play the disabled characters or not,” says Pašović. “We knew that there has been a lot of progress in recent years thanks to activism that is now pointing social attention towards the disabled world. It‘s very strong in our region and people are creating different forms of raising awareness and making work that includes people with disabilities – there have been good theatre shows, for example, with interesting results. But we’re in professional theatre and we eventually said, okay we’re not going to enter the activist field because we are not activists so let’s do the show as we would do any other show, let’s give our best artistic ability to the subject and work to transform the experience from our research to the performance itself.”

For historical, economic and society reasons, the reality is that for the industry to include disabled performers, the first step has to be physical access at all levels to the buildings. No access = no audience = no show. It’s the theatres and not the shows that have the agency to step in to remove barriers to building an audience that is representative – if not at the moment to see themselves on stage then at least to see their stories. And also to be free to see any other show like non-disabled theatre-goers, where the only barrier is the cost of the ticket or whether it’s a good show or not.

“All the theatre buildings we play in have good access. This is a precondition for any space for World of Possibilities to be played in,” say Pašović. “Obviously we want our primary audience of disabled people to come and to see the show, we want to set an example for physical accessibility. But the scale of what needs to be done in the region is huge and this show is where we ourselves have started. We have learned from World of Possibilities that we can’t set ourselves up to be representative for everybody. We don’t want to claim that we have covered everything because we haven’t. It’s a big world that one piece of theatre cannot possibly cover all its aspects, and so we can only encourage venues to improve their physical access.”

The partner theatres have spread the word to disabled audiences by reaching out to the institutions and organisations linked to disabilities in each country. Pašović also wants them to reach the general audience “because it is the general audience that needs to learn that the world we all live in is far more complex for disabled people”. The mere fact of playing these theatres also speaks volumes. “One of the ways to fight the lack of awareness in society is the show itself because it is produced to the high level you would expect of the big theatres. So the very fact that these established institutions are putting World of Possibilities on an equal basis with all the other repertory works contributes to fighting any stigma.”

On another level, the play highlights the reality of the barriers of daily life, from mobility to acceptance within society. ”Society is still struggling to answer these questions. There are all sorts of different solutions being discussed and sometimes implemented, but there is not yet a systematic solution for this. Again, it’s a huge spectrum so we had to focus on a section of this world in order to be able reach out in a single play. We would love the show to inspire other artists to carry on working this way.”

Haris Pašović with artists and specialists during workshops at the

Milan Petrović school and centre in Novi Sad”

The lack of inclusion of disabled people is just one of the many ongoing issues that the Balkan nations have inherited from Communist times and after. Addressing it is low on the list of political priorities, and if there is back-slapping over the introduction of inclusive legislation, especially by the EU member states, it does not follow that there are the resources or even the political will to turn this into reality. Sign language rights are now, however, a highly visible step for legislation all over the world, and the Balkans are in a good position because the national variants of Yugoslav Sign Language parallel the region’s spoken languages.

“We are working on adding signed performances and also how to incorporate subtitling, which is not just for foreign languages but also our own,” says Pašović. “As we do more performances, we will need to have conversations with the responsible institutions in each host city to establish what is possible based on their knowledge of the potential audience.”

So while it may not tick all the boxes, World of Possibilities is definitely helping to open up conversations around disability in the Balkan nations. “As theatremakers, it’s our artistic duty to consider the world in its totality and how disability is a part of that totality,” says Pašović. “We want to remind general audiences that humanity is much more than rushing after material things. We also want also to push the artistic world because it is so often pressurised by commercial demands, lack of funding, censorship or opportunism, so the easy option is usually to go for the fashionable subjects instead of diving into the hard realities.

“We’re pointing out that there are other, different groups in our society and when you work in a public institution you are obliged as an artist to address all of them. And this includes those who are with disabilities or ethnic minorities or sexual preference or people who are in need whether they are poor, whether they are migrants, whether they suffer injustice. If you work in theatre, you have to know that anyone who is excluded must be included.”

Nick Awde is a director of Seeking Talent, working with poets and artists with special educational needs and disabilities to perform in non-traditional spaces.

Main photo: Salvatore Esposito

For more information, visit: enabledtheatre.com

Further reading: review of World of Possibilities

Nick Awde is a journalist, playwright, editor, critic and producer. Based in the UK, he is co-director of Morecambe's Alhambra Theatre. Books include Equal Stages (diversity and inclusion in theatre), Mellotron, Women In Islam, and translations of plays by other writers. Much of his work focuses on ethnoconflict and language/cultural genocide.