Choreographer Igor Koruga talks to Borisav Matić about his new dance piece Unstable Comrades, his research in the history of queer culture in socialist countries, and performing queerness through dance.

Borisav Matić: Your new performance Unstable Comrades deals, among other things, with queer culture in socialist countries, a topic that is often neglected in research and artistic practice. How does the performance approach this theme?

Igor Koruga: When I started to work with that question of queer culture and socialism, I needed to question queer heritage that’s not only the creation of Western, liberal and “emancipated” societies, but rather has other histories and legacies such as cultures and societies which, throughout history, had a form of communism or socialism.

Before I started working on the performance, I had a very long research process in which I tried to understand these phenomena in countries like Yugoslavia, Romania, Eastern Germany, and Russia, and how they differed from Britain and North America.

I searched for performative and choreographic approaches and procedures in those socialist and communist environments which were either in touch with queer or feminist practices or didn’t declare themselves necessarily as queer but had such characteristics. I focused on the conceptual art which developed in Yugoslavia in Zagreb, Ljubljana and Belgrade. There was, for example, punk culture which was the platform where queer practices arose in Ljubljana during the ending moments of socialist Yugoslavia – for example, in ’84 in Ljubljana, there was the first gay pride Magnus Festival… or the Partisan dance practices during the Second World War and constitutional moments of socialist Yugoslavia.

In all those approaches and ideas, I was searching for artistic proposals that I tried to carry out in the work with the dancers. I was much more focused on the procedures which artists in those periods were using and how they opposed dogmatization and authoritarianism.

There are, of course, different socialisms and communisms. The situation is not always the same. The same type of dogmatization wasn’t present in Yugoslavia as it was in Romania. But what is interesting to me is the ways in which queerness questioned the dogmatization of socialism under strong patriarchal governance.

What I think is crucial is that socialism as ideology or practice, in a sense even Marxism, has values rooted in queer culture. They are somehow merged, at least in our socio-political circumstances. Queer carried a kind of resistance and confrontation in socialist countries. Through the performance, I tried to show different aspects of that queer punk confrontation and questioning.

Borisav Matić: This performance arose from the SEEDS project – South-East European Dance Stations – so the experiences of Romania and Bulgaria are included. You are also dealing with former socialist countries like Russia and East Germany. Have you gained insight through working on this performance into how much queer culture differed in those countries with their different socialisms?

Igor Koruga: It was a matter of how much queer and feminist practices enjoyed greater or lesser tolerance or intolerance in different socialist or communist contexts. If we’re talking about punk culture at the end of the 70s and the beginning of the 80s in Yugoslavia, it was a cultural and artistic movement in which many other movements occurred, like feminism, queer practices, anti-imperialist movements, ecological movements.

Yugoslavia was restrictive towards queer culture, but there were rifts through which queerness could survive. In my previous performance Desire to Make a Solid History Will End Up in Failure, when Milica Ivić and I talked with artists and performers, we asked them “Do you remember the first queer and feminist occurrences in the 70s and 80s?” They were always telling us that was all normal then, that was somehow around us, there was no big drama, someone coming out, etc. – it was more a part of everyday society. For example, when you compare [the situation] until ’77 when homosexuality was decriminalized in Yugoslavia, there was a much smaller number of court processes for homosexuality in Yugoslavia than in Germany and other Western countries.

Borisav Matić: In Western Germany?

Igor Koruga: That’s right – actually, both in Western and Eastern Germany. A much bigger number of court processes was present there. It’s a really big ratio. Socialist Yugoslavia did not stifle queer culture repressively, like some other countries, but it was accepted that queer culture must stay within four walls. However, when punk occurred as a need to question socialist dogma and socialist bourgeoisie society through queer-feminist practices, even then in ’81, ’82 the authorities created the so-called Nazi affair, accusing every punk that they are a Nazi. They would be taking them to the police, questioned them, follow them, placing them under surveillance. So, nothing can be seen as black and white.

In contrast, if we look at Romania, the writer and literacy critic Ion Negoițescu came out to his parents and publicly when he was 16. He critiqued the communist regime all the time. He advocated for some much more pro-Western ideals, but he openly criticized and constantly suffered various kinds of mistreatment. He was taken to prison, expelled from Romania and then returned. Some societies were more repressive. While Yugoslavia had greater tolerance, socialist dogmatism was very present in Yugoslavia and in some ways repressive, because everything different was essentially not tolerated, but it’s not like they persecuted and harassed members of queer culture.

Those are all the findings and discoveries that I made in the course of preparation for this creative process and work. Unstable Comrades doesn’t have the archival framework of my previous work, Desire to Make a Solid History will End in Failure. but I think that for me all this research is only the beginning of analysing this topic. I found it very exciting working with young people on the performance who may have a different relationship towards queerness or the heritage of queer culture. It was remarkable for me to see how they connected with all these things and, on the level of physical movement, how we can represent all those things and how they correspond with the contemporary moment.

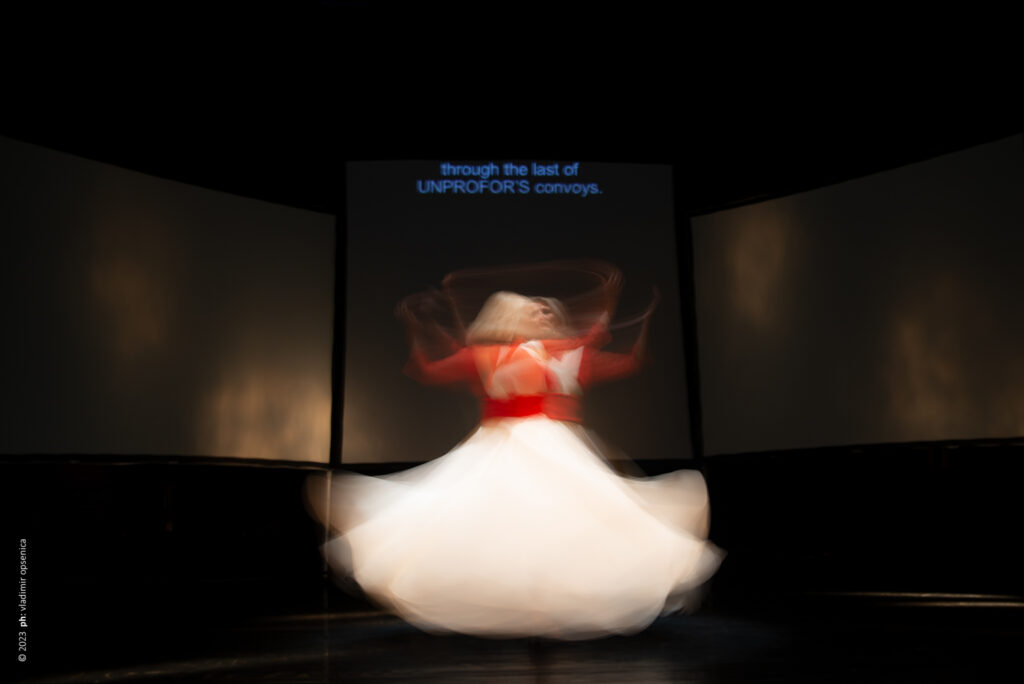

Unstable Comrades, Atelje 212/STANICA Photo: Vladimir Opsenica

Borisav Matić: The performance compares queer culture in socialist and Western countries. On which examples do you focus in the performance when it comes to Western societies? What did you learn during the process about the relationship of queer cultures in both these contexts?

Igor Koruga: I focused on those queer punk movements which occurred in the second half of the 20th century, for example, the queercore movement in Britain, Canada and the USA. It also questioned the middle-class society and opposed that bourgeois normalising approach. But it also critiqued the Christian, religious aspect and the idea of family and normal life.

Film directors like Bruce LaBruce or John Waters, or artists like Vaginal Davis, the Popstituets, dealt a lot with the idea of merging queer and punk, until punk became too masculine, misogynistic, homophobic – so they questioned that as well. Furthermore, they turned self-critically towards questioning the dogmatization of the LGBTQ+ political movement: commercialization of pride (No Labels, No Apology, No Assimilation) pink-washing, the idea that gay individuals go to war to drop bombs in Afghanistan, homo-normativity, political correctness, identity politics (sexual identity is not the centre of sexual orientation) etc.

In the American context, in the second half of the 20th century there were two streams of approaches among the LGBTQ+ community. On one hand, there was soft stream in 1950-60s (Mattachine, Daughters of Bilitis) advocating for the idea that – as long as queer can be present in public and the rights to marriage, adopt children and serve in the military can be exercised – that was already considered a big step forward. On the other hand, some very short-term practices existed – I specifically mean Stonewall and the Gay Liberation Front – which advocated for radical approaches and protests and the rejection of the idea that a family must consist of two individuals of the same sex and gender, and in a way they advocated for the idea that sexual identity and gender identity have many different categories and sub-practices within them.

They advocated that the emancipation of gay culture or queer culture will not happen by submitting to the heteronormative, they would rather continue to question it very radically and oppose it. They fought for a world where women would have the same power as men, be equally strong, and play the same role in public life, while men would be equally gentle and emotional as women, play an equal role at home, and be equally caring towards children. They used transvestism and “genderfuck” to cross and confuse gender boundaries.

In liberated culture, everyone would in principle be open to erotic relationships with men or women, and any inclination that might exist would lose its social significance. Besides leftist gay men who admired macho revolutionaries, there were anti-macho groups like the Effeminists, Flaming Faggots, Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) – founded in 1970 by trans activists Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson, also active in the GLF – and Queens’ Liberation Front. Radical feminism permeated other ‘second-wave’ trans groups like the Transsexual Counseling Service, Transsexual Action Organization, and others.

For me, it’s interesting that in the historical context of the USA, all those more radical practices came from the circles of communist, socialist and feminist environments. All that directly questioned the heteronormative, gender normatives and capitalist ways of production – including class differences – that stand behind the definition of heteronormative. Those were all more radical practices that were actually some kind of a model to socialist countries like Yugoslavia. It’s just that the same models could not be applied in different contexts. I have a great need to say – it’s certainly a political stance – that the liberalization or emancipation of queer culture is not just a Western creation. In our context, it’s not only a Western European, but it is also an Eastern European, socialist and communist creation. Perhaps there was not an equal balance of power, but that was again a consequence of class differences and privileges between the West and the East.

Unstable Comrades, Atelje 212/STANICA Photo: Vladimir Opsenica

Borisav Matić: Dance and queer culture have often been inextricably linked. How much was dance a convenient remedy to explore queer culture in Unstable Comrades?

Igor Koruga: It’s a very inconvenient remedy. In the historical or archival research of dance, it is very difficult to get information about how dance behaved, through which concrete examples it appeared and how it manifested itself. My research approach was to understand those first queer appearances which occurred in public. I was especially interested in the ’70s in Belgrade and at the Student Cultural Center where we first have the emergence of new conceptual art, where artists like Marina Abramović, Raša Teodosijević, Neša Paripović, Zoran Todorović, Katalin Ladik emerged. In addition, my focus included conceptual performance artists in Zagreb (Vlasta Delimar, Sanja Iveković) or Ljubljana (Marina Gržinić, Aina Smidt, Aldo Ivančić.

But I also found it interesting that through that New Wave of rock, the stream of the so-called Belgrade pop art appeared which featured artists like Kosta Bunuševac, Robert Hirschl, Vladimir Jovanović, and even Nebojša Pajkić, who created or were behind New-Wave bands like Idoli or pop singers like Oliver Mandić. Bunuševac created the TV show Belgrade at Nigh with Mandić in the ’81, the first time that a man appeared in drag or women’s clothes on national television. Bunuševac and Mandić, teamed with choreographer Petar Slaj who at that point worked a lot with modern dancers, created different kinds of dance both in theatre and commercially. Paradoxically, some of these pop-art practitioners took some very contradictory and problematic political stances 15 or 20 years later, especially when wars appeared.

All these artists did different kinds of performance art and body practices in which dance was certainly present. I don’t claim that Abramović or Teodosijević were doing dance, they were very clearly doing performance art. Related to the performance and the physical work, it was interesting to me to explore methodologically some concrete artistic procedures. For example, in punk culture in Ljubljana, Marina Gržinić had very clear, direct sexual and feminist works in which she first of all questioned women’s sexuality and sexual desire. Likewise, in her work with the punk band Borghesia, she questioned queer and gay relationships.

What came to my focus was how she was handling the procedures of looking, of the gaze in her video works. Through that kind of gaze, she acknowledged the way socialist society looked at and judged those who were different, who rebel, who are advocating for some sort of emancipation and pluralism. The same goes for Delimar, Iveković, Ladik, and others. Bunuševac would drag up, put on women’s leggings, earrings, make-up and he would have some kind of a performance where he would sing and dance. Or he would have concerts with Koja from Disciplina kičme and have some kind of a public dance performances.

Archivally and historically speaking, we can’t say that there are clear examples of queer dance, as it can be found in East Germany among modern dancers. But that doesn’t mean that it didn’t exist, it is rather a matter of searching and unearthing archival gems. I went back to the inter-war period of Yugoslavia when dance was very much engaged in the communist and antifascist struggle for freedom. During the Second World War, there were artists like Marta Paulina Brina, Žorž Skrigin and Mira Sanjina who performed during the war on improvised stages in front of the Partisan army, the National Liberation Army, motivating them to continue to fight and not surrender. Sanjina danced in ’43 at the second session of AVNOJ (Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia) when Yugoslavia was constituted. No one of them was queer. Perhaps we can emphasize the feminist aspect of dance there. On the other hand, we can’t neglect the fact there were certainly queer members in the Partisan army. Somehow in all that, I found it interesting to search for physical expressions that questioned the norms of society, even if they were not always connected to queerness.

Borisav Matić: Unstable Comrades draws on the abundance of material from queer histories. How do those historical examples communicate with our current moment?

Igor Koruga: The artistic questioning of heteronormatives was very important and inspiring to me because it is challenging to artistically question queer culture and the problems it faces today in neoliberal-capitalist society – gender conformism, marketization of identity, gender binary, overidentification of sexuality – without falling into the problems of stage illustration, above all of the different stereotypes about the queer. For example, how can gender non-binary be performed on stage without involving the already-known practice of cross-dressing? That’s why I put a methodological focus on the procedures of watching, understanding, showing, experiencing the behaviour, body movement and dance on stage, exploring the domains of intimacy and tenderness. authenticity, eroticism, negative feelings, as a feature of queerness, both on an individual and collective bodily level.

For me, the body and physicality are domains that do not have the same logic as when the language is declaratively spoken on stage: I am queer. The body also has different ways of communicating, and the procedurality of that within the practice of contemporary dance sometimes tries to go beyond the representation of a theme, more toward the experiential experience of that theme. Therefore, for me, this performance should not be seen so much as a performance about queerness – presenting its development, existence, equality rights – but perhaps more as a performance that does queer both on the level of the behaviour of dancer’s bodies on stage (through various physical, affective and attention choreographies) and the level of perceiving those bodies (from spectators), feeling their affective manifestations etc. I don’t know to what extent I succeeded in that, but it certainly inspires me to continue to explore it in my artistic practice.

Desire to Make a Solid History will End in Failure. Photo: Vladimir Opsenica

Borisav Matić: In your previous performance Desire to Make a Solid History Will End Up in Failure, the relationship between history and the independent dance scene may seem so incompatible because of the ephemerality of dance and the marginalization of the independent scene. Even in the title, you put that a solid history cannot be made.

In Unstable Comrades which deals with the relation of queer culture and history, you completely give up on representing the archival material. Is it even more difficult to deal with the relationship between queer culture and history than between the independent scene and history?

Igor Koruga: Essentially, I was still involved in archiving, and the preparation of this performance is very much a continuation of the archival work of previous years, it’s only that queerness is explored more. But what is the continuation is the issue of failure, because I rely very much on the idea of an unhappy queer who constantly point out problems within society and dogmatization.

I see a connection between the two performances in this idea of failure, or impossibility, which is not necessarily bad, but a consequence of much wider social, political and economic circumstances that are simply the way they are. It’s difficult to get to the archival materials but, on the other hand, I reject to believe that they didn’t exist only because currently we don’t have them. There are certainly some, it’s just a question of where they are and how to get to them. When we talk about all that, I think that actually, the situation is the same.

When we were working on Desire, whenever we came to some small piece of information, we were very happy. But in the wider context, that’s only a needle in a haystack. It’s the same here. But that failure drives me to further questioning.

For more information, visit: dancestation.org

Further reading: review of Desire to Make a Solid History Will End Up in Failure

Borisav Matić is a critic and dramaturg from Serbia. He is the Regional Managing Editor at The Theatre Times. He regularly writes about theatre for a range of publications and media.

He’s a member of the feminist collective Rebel Readers with whom he co-edits Bookvica, their platform for literary criticism, and produces literary shows and podcasts. He occasionally works as a dramaturg or a scriptwriter for theatre, TV, radio and other media. He's the administrator of IDEA - the International Drama/Theatre and Education Association.