Shakespeare’s late play Pericles is rarely staged in theatres in Southeast Europe. Borisav Matić talked to director Philip Parr about his recent production of the play for the Hungarian State Theatre “Csiky Gergely” in Timisoara, his international career and the difference between UK and continental approaches to Shakespeare.

Philip Parr’s production of Pericles provided audiences with a rare chance to witness the performative allure of a Shakespeare play that, while not one of his best, is still a potent play for an ensemble performance with many contemporary socio-political connotations. Parr has directed Shakespeare’s plays in countries across Europe and is s a founding council member of the European Shakespeare Festivals network and director of the York International Shakespeare Festival, which gives him how Shakespeare is performed both in the UK and on the continent. He has also worked in opera, as an actor, singer, musician and composer, all of which informs his new production of Pericles.

The interview was edited and condensed for brevity and clarity.

Borisav Matić: Pericles is one of Shakespeare’s less performed plays. What attracted you to direct it, now more than once?

Philip Parr: Interestingly, Pericles is getting more performed in Britain. The RSC [Royal Shakespeare Company] has made two or three productions in the last fifteen years or so, which is a lot for a play they’ve never done before. It’s a really nice ensemble piece, one of Shakespeare’s plays that isn’t about a central character in the world that radiates around them. I’m very fond of Shakespeare’s last four plays, so, Cymbeline, The Winter’s Tale, Pericles and The Tempest, which I think sit slightly separately from all his other work. They feel to me like mature plays, they’re not written with any particular agenda. The political and social sensibility is still there, but unlike Macbeth, for instance, or the history plays, he’s not writing to please someone else. They feel like the plays of a mature writer writing the plays he wants to write, and they share a common thread of a father-daughter reconciliation, and within all of them there’s a message of hope, a message of possibility. It’s not a sugary saccharine message of hope. In The Winter’s Tale, Leontes’ son is dead at the end. He losses, people loose. They experience life but gain humanity. That is at the heart of all of Shakespeare’s writing, but it’s most openly defined in those four plays. Pericles comes to a realization that there’s more to a rich and fulfilled life than a sense of entitlement

Borisav Matić: Shakespeare wrote Pericles after a series of tragedies and this is a play with a distinct optimistic ending. When choosing to stage the play, did you think about the need for optimism in today’s society?

Philip Parr: Yes, very much. If you’re going to stage Shakespeare’s plays now, and we talk about Shakespeare’s plays being timeless, then you can’t stage them as historical artefacts. The audience comes with their sensibilities of 2024, not with 15th or 16th-century consciousness. You need to think about where the resonances are.

Pericles is a character who suffers through his sea journeys. It just resonated so strongly with the number of stories that certainly in the UK we see every day. This obsession with small boats, migrants and people making dangerous journeys and needing to take a risk –such a position as Pericles is at the beginning, when he realizes that not only is his life under threat, but that if Antiochus wants to keep his secret, he’s just gonna come and kill anybody he thinks might know it. Therefore, Pericles’ only option is to go to sea. He loses everything, he gains everything, and he loses everything. It’s all to do with this risk-taking against the natural element.

What I felt really important, and one of the things Shakespeare is saying, is that we need to keep the power of our stories alive. Our stories, and arts and culture generally, are what make us human. We need to remind ourselves – that’s what creates individuals and us as human beings. That was the optimism we were looking for. A displaced community on a beach somewhere, they went away without material wealth, but in their hearts they’ve been reminded of the humanity through storytelling and, by extension, theater.

Borisav Matić: Many theatremakers who wrestled with directing Pericles said that it has a lot of qualities that make it very convenient for staging. But on the other hand, some even call the play a structural mess in terms of dramaturgy. There is even a theory that Shakespeare didn’t write the first two acts…

Philip Parr: He definitely didn’t write all of it. I don’t know that I’d call it a structural mess. It’s a long epic narrative. His collaborator [George] Wilkins publish it as a prose work. They thought of it in a kind of Victorian sense – they released this episode and made it exciting, and then see who wants to turn the page for the next one. It is a kind of page-turner. And they throw everything at it, pirates and incest. If you can have a bit of sensation, you get it in there. I’m not sure Shakespeare would have needed that much sensation. You can see where he might have come in and just put this good speech that’ll tidy that scene up.

I like it. What makes it good for an ensemble, you see a range of people. In a way there’s something mysterious even with Antiochus. You can abhor what he does. But as Gower [the narrator] says, his wife dies, giving birth to their daughter, his daughter grows up and looks like his wife and he can’t tear his memory. So he does a bad thing, it’s human. In every one of those characters there’s a little sliver of humanity.

Pericles at “Csiky Gergely” Hungarian State Theatre, Timișoara,

Borisav Matić: When adapting the play, how did you and the dramaturg Dálnoky Réka deal with these problems that exist in the text? You chose to be very faithful to the story?

Philip Parr: There’s been a bit of discussion recently about the difference between the UK text-based theatre-making and European experimentation. I wanted to find some common ground between the two. I do think that when we ask the writer to create something for us, our job is to interpret, take that forward and not second-guess the writer. You want to do that, you write your own piece, devise or find another way to creation. It is your duty as a director and a dramaturg to shape that piece in a way that will work for your process but not make a change just for the sake of making it.

I was asked by the [“Csiky Gergely”] theater to make a play: “You come and make Shakespeare with us. We want the kind of Shakespeare you make, for our company to experience, but we don’t want a period-costume firesteel-style piece. We wanted to have freshness and blend some of the areas of skill.” The choices we made are led by setting the piece within a group of displaced people. We don’t refer to them as refugees, because they’re a little bit timeless. They’re not localized in that way. There should be enough clues in there to give you a reference to all the possibilities of displacement. As we know, tomorrow we might be displaced. I don’t think that Ukrainians or the Gazans quite thought they’d be displaced. And constantly, people are on the move for all sorts of reasons. All of the actors have a backstory they’ve created that tells them who [their characters] are and why they’re there.

The other thing common to Shakespeare’s last four plays, he has a deus-ex-machina moment. We think that’s something to do with the fact that he’s playing them both on the outdoor stage of the Globe and the indoor stage at the Blackfriars. Blackfriars has control of light, so you can start to do new things. So we needed to find our way around that and look within some of the scenes, particularly the caravan scene, about how that fits into a contemporary world. From the outset, I had in my mind that I wanted the end of the play to sit within the real world, not the theatrical world, to hopefully have a different impact. So just lots of tweaks and changes and we end up with multiples of people. The idea of having Pericles as two actors to age in between came from a conversation with another director many years ago.

Borisav Matić: There’s this very delicate balance between an approach that’s faithful to the text and the need to be playful with it and make it more relevant to our society. The costumes and the set design are central in your approach of making the play more explicitly relevant to our society?

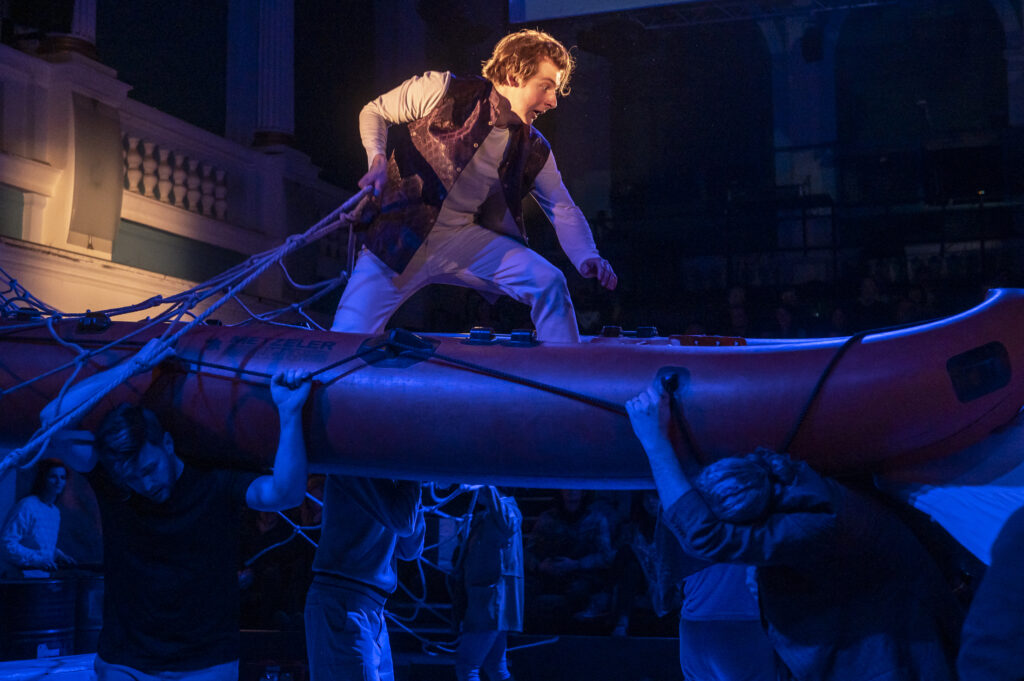

Philip Parr: Yes. We wanted a very simple set. Partly from being in this space but also from the nature of the product, we wanted to be in traverse, so the audience sees themselves as well. As soon as you do that, you’re telling the audience they’re part of the play in a different way. Brian [D. Hanlon] handled the design and came up with the idea of drawing on the net and the sale, and then we played with those in different ways. Then we came up with the idea of the floor [painting of the sea]. I already had the idea that the first image was of a man in a boat, you had to walk into the image of a man in a boat and you don’t know whether he’s alive or dead. And you don’t know his story. You should look at him and wonder what his story is. We’re very lucky we found an orange boat. It’s like another member of the cast, it’s been at every rehearsal. That, if you like, is the modern setting.

Borisav Matić: And what is the role of dance and music in this performance? How did you work with the choreographer and composer to create the show?

Philip Parr: There are certain things that seem to turn up in every show I make. Music has always been one of them. For me, you need to see the source of the music. 99 times out of 100 times that means the music is live and ideally played by the performers, which it is in this case. This is interesting because [Cári] Tibor – who’s the resident composer here, we know each other quite well – he’s never done that before. He writes fantastic, beautiful scores, takes some musicians and they record. It’s played or he brings in musicians to be part of the show. Whereas by coming from the other side, I say “what do you play?” “I played the flute when I was six.” Okay, take this flute and tell me what you can do. Okay, I just need that note, that will be enough. We’re very lucky that we have a fantastic guitarist Kiss Attila. He’s been also part of that creative process and a lot of that was “play that and we will fit it in”. You listen and play. It’s a holistic experience. Tibor has come up with some phenomenal music. And what this company does really well is sing. They sing difficult, complicated music very beautifully. I aksed him [Tibor] for three or four pieces of music which turned into about eight, because we keep adding another song. Shakespeare stupidly didn’t write us a song for the brothels [scene], so those are the words from Henry Purcell’s rude song which he set in a completely different way but it fits within.

It’s the same with the dance, with Anca Stoica. We haven’t worked together. I was asked if I’d liked to work with her. She sent me some choreography. She’s a very young and good contemporary dancer. I liked the way that she made bodies work and cared about them. It’s her first theatre choreography. We knew there was going to be a dance. I knew that at the end of the play, the eventual celebration, I wanted to draw on the concept of the jig. But there are also other things she’s been working with the actors on moments of gesture and movement and just the style of playing as well. Those human layers that we have to work with, music and dance particularly, become valuable elements in there. For me, I think there will probably always be music and dance somewhere in a show, particularly music.

Borisav Matić: I get the sense that this production is strongly influenced by your work in community theatre, not only in the topics, but because you use the skills of the actors like their music skills. And you already directed Pericles in 2010 as a community performance for the International Shakespeare Festival in Gdansk, Poland. How do you compare this 2010 production with Pericles at the Hungarian State Theatre?

Philip Parr: They turned out completely different as they should be. One of the things you learn from work with communities is that each community owns that play, you can’t really transfer it onto another group. The individual skills they bring color the moment. It’s the same thing with this group of actors in that they do have different skills. I want them to have ownership of the piece. It’s all so quite fluid, it shifts and changes. The actors mustn’t be automatons beautifully performing something. If they’re performing it, they’re not being it, not feeling it. That’s been quite an interesting challenge for the actors because that’s not always the permission they’re given. But they must bring themselves to the piece. My job is to invite them to play the roles that I think they will play well, but not to tell them how to do it. I invite them to argue when I cut a line if they feel that line is important. If you allow the actors the capacity to inhabit what they do, then they really stay in that role. And the actors here are particularly good at just owning and building that kind of character, and they’re living inside it for over two and a half hours.

Pericles at “Csiky Gergely” Hungarian State Theatre, Timișoara,

Borisav Matić: Do you see any particular difference in method and technique between actors in this region – for example, now in Timisoara – and British actors in performing in such plays?

Philip Parr: Yeah. I was fascinated here by how quickly the actors want to put their scripts down, but continue to be prompted. The prompter is in all the rehearsal process. Because they want to be free for the physicality of the piece, whereas a British actor will hold the script in their hand for as long as possible. They’ll get it out of the way, but they know they don’t detach from it. There’s a sense that the thinking process informs the pauses, not a physical process. A British actor is probably looking for a through line of thought. It’s been fascinating to draw those two together, and I think that’s been part of the reason for the invitation, to bring that challenge, and vice versa, for me to work within and understand that capacity and possibility. It’s certainly that both have influenced the production.

Borisav Matić: Do you think that the differences come from the position of Shakespeare’s text in Britain and that actors may have a mix of respect and even fearfulness towards it, while actors here are more freely engaged with the text?

Philip Parr: There is sometimes an obsessive respect for the text in Britain. It’s not just Shakespeare, it’s any play. Mirroring, think of Beckett, where if you change a word, move a full stop, and you’re in trouble… and Pinter. The writer often defines the piece. And it’s interesting to see when writers in English, Sarah Kane particularly, and David Greig are really starting to say – no, just put some words here, don’t know how many actors there are in this piece, you choose. That’s quite a difficult challenge for people. Not every director, every actor wants to come at it. The ability to be freer with text is so much better in translation. There are in fact two Hungarian language versions of Pericles. Then you get a choice. Do you want to play this or that cut? Once you’re at that point you say – well, we could change this, move that. It’s not, “Will anybody jump on us if we move this speech from here to here?” I like the freeing quality of that. That’s altered the way I go back to the UK and make Shakespeare. There’s so much Shakespeare that’s not in English. I wish more UK directors of Shakespeare took that opportunity to understand how freeing up that is, while still maintaining a reverence for the text. I suggest that everybody should rewrite Hamlet into modern English. It’s an interesting experiment which has been done. But we play those plays in [Early Modern] English for a reason. Some of those lines are beautiful, even if they’re difficult. They have a quality through which the writer deserves respect.

Borisav Matić: Directions of Shakespeare not only explains the text but also the culture of the director or the production house where the show comes from. As someone who is the Director of the York International Shakespeare Festival and a founding council member of the European Shakespeare Festivals network, what else have you learned about different national attitudes towards Shakespeare?

Philip Parr: I came to Shakespeare late. The majority of my early career was in opera and I came into theatre through community theatre and then to Shakespeare through festivals, through being a festival director, and onto directing Shakespeare in community plays and so on. The eye-opener to me was this level of freedom and then looking around the realization that more Shakespeare gets played not in English than in English. You think of the big Shakespeare festivals like Craiova and Gdansk, it’s the wealth of passion for Shakespeare in other places and you hear people talking about why Shakespeare’s important. Shakespeare’s lost that kind of currency in the UK. Shakespeare is historical – “It’s a bit difficult, should we be teaching it, is it relevant?” Absolutely, it’s relevant. Just open your eyes and look at why it’s relevant to other people. It’s beginning to shift in the UK. They’re starting to think, why this play at this time? But everywhere else in the world, it’s absolutely – “I need to make a point with this play.” And then if I need to make this play but leave the first act out because my point is here – fine, that’s what you do. It’s about keeping theatre-making fresh. Learning that gives one massive hope that Shakespeare is more than just a Shakespeare-tourism industry.

For more information, visit: tm-t.ro

Further reading: review of Pericles at Hungarian State Theatre “Csiky Gergely”

Borisav Matić is a critic and dramaturg from Serbia. He is the Regional Managing Editor at The Theatre Times. He regularly writes about theatre for a range of publications and media.

He’s a member of the feminist collective Rebel Readers with whom he co-edits Bookvica, their platform for literary criticism, and produces literary shows and podcasts. He occasionally works as a dramaturg or a scriptwriter for theatre, TV, radio and other media. He's the administrator of IDEA - the International Drama/Theatre and Education Association.