Director Selma Spahić talks to Darija Davidović about the legacy of the wars of the 1990s, post-Yugoslav artistic collaboration, the role documentary theatre has played in her work and the importance of communities.

Selma Spahić has directed at theatres in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia, Montenegro and Germany. She was the artistic director of the MESS festival from 2012-2017. In March 2020, she staged and co-wrote The Clickworkers with Dino Pešut as part of the Europa Ensemble at the Staatstheater Stuttgart. In November of this year, her play Moja Fabrika (My Factory), based on the book of the same name by Selvedin Avdić, will be presented at the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin as part of the LOST – YOU GO SLAVIA season curated by the director Oliver Frljić.

Darija Davidović: War is one of the main topics of your artistic work, which is not surprising considering your experiences of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Your recent production of Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot for the National Theatre Sarajevo contains criticism of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine. Was this a decisive part of your staging of The Idiot?

Selma Spahić: The war was not decisive. In a conversation with Dino Mustafić (theatre director and Director of the National Theatre Sarajevo) and Vedrana Božinović (actress and Director of Drama of the National Theatre Sarajevo), I had agreed that we would stage The Idiot before the war began.

The scene about the war was a continuation of Mishkin’s renowned monologue in the novel. The alarming messages in today’s context was something to which we had to respond. We carefully dramatized the novel, paying attention to everything and thinking about the society in which we are staging the novel today.

We dealt with money as the driving force of the young generation, the pressures of capitalism, individualism, social prestige and success, the violence and “neuroticism” of today’s world, the inconsistency of attitudes and opinions, the constant anxiety, the gap between generations, the fact that kindness can be manipulated very easily, and the question of personal responsibility….

We tried to preserve the omnipresent polyperspectivity of the novel, the dialectics of Dostoevsky’s ideas. The Idiot is a masterpiece of world literature, and our performance is based on it – it remains in constant dialogue with the themes of the novel from a 2023 perspective

The Idiot – National Theatre of Sarajevo. Photo: Velija Hasanbegović

.

Darija Davidović: How do you choose the texts on which you want to work? Which are the criteria?

Selma Spahić: It depends. Sometimes I read a text and I know right away I want to stage it so I wait for an opportunity; sometimes the theatre offers the text, sometimes I search for a long time, sometimes I decide very quickly. Over the years, I increasingly trust my first instinct as the process of staging a material always goes through different stages – ranging from resistance to romanticization; therefore, it is important for me to remember that first feeling. If I want to stage it on the first read, I am usually able to return to that initial motivation.

Darija Davidović: Your work deals with politically and socially relevant topics, not just war, but the role of religious institutions, the state, and the family. You often explore the younger generation and their view on the world and society. How do you see the relationship between your work as an artist and the society in which you live in? Do you feel in any way responsible to society as an artist?

Selma Spahić: I articulate my thoughts best through the theatre; there I find a way to open a dialogue about the topics I consider important. Theatre allows for the addressing of a subject from many angles, in a world where everything is over-simplified. It is difficult to predict how the piece will communicate with the audience, and there are so many factors at play– the choice of material, the form I choose, the policies of the producing theatre, the quality of the rehearsal process, the moment when the topic is introduced – too early or too late or at just the right moment… Over time, I have learned that there are many things you cannot control. I feel a responsibility to make sure that what the audience sees is well thought out and done with utmost dedication – to provide a basis for them to form their own opinion.

Darija Davidović: How did the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s affect your artistic work? Is the impact of the war omnipresent in your work, or were there moments when you felt you couldn’t or didn’t want to deal with it anymore?

Selma Spahić: They were very influential and still are because they seem to have continued, only in a different form. Our daily life is filled with threats of new wars, overt or covert censorship, nationalistic narratives, glorification of crimes.

I do not always deal with war, not even with its direct consequences; it seems to me that I always deal with patriarchy as a recurring topic, but since these are very intertwined in our region, I always touch on them in my theatre projects – either me or the authors of the texts I work with. I think that all of us who feel resistance to current political developments, not only in our region but all other places seeing the rise of the extreme right-wing, do not want to or cannot deal with it, but we do not have much choice. The result of the last 30 years of politics in our region is a new generation in which those who are completely indoctrinated with nationalism are much louder than those who are not, therefore, resistance in the arts is a necessity.

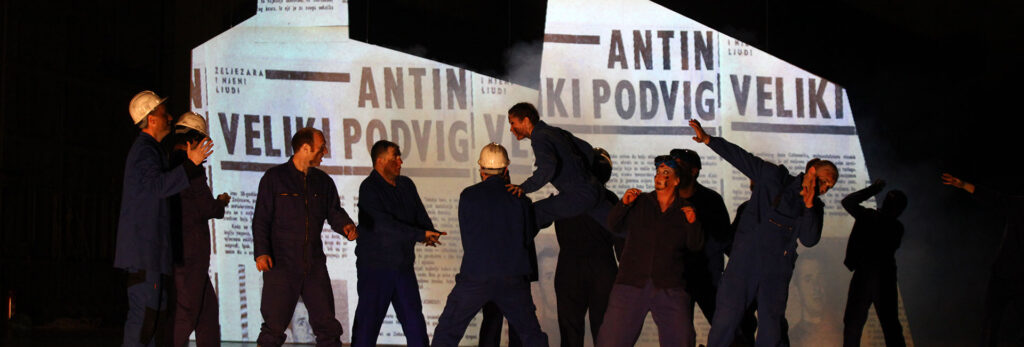

Moja Fabrika

Darija Davidović: You have a reputation as someone with an activist approach to your artistic work. Is this a description you identify with? How important are these attributes for your identity as an artist?

Selma Spahić: I often think about the impression I have that politically more explicit and courageous actions have been undertaken in the theatre in our region a decade or more ago.

I have always perceived myself as someone who deals with intimacy, intimate history and, naturally, the political aspects of intimate history. If we have reached a point in theatre-making where a reasonable reaction of resistance to injustice or crime, or the struggle for women’s freedom to decide about their bodies trespasses the threshold of tolerance for conservatives – and we have seen examples where they do not hesitate to physically stop performances – then we are in serious trouble.

This is what Zlatko Paković has been warning about for years. His every performance causes reactions that can be dangerous for him and his ensemble, because he articulates opinions that majority politics do not accept nor do they allow it to be heard. I may not have answered your question, but I needed to share my fear about the point we have reached.

Darija Davidović: Some of your work – including My Factory and The Hen – were created using historical documents and archive material. How do you deal artistically with historical material?

Selma Spahić: I love documentary theatre because the creative process is exciting in many ways, both in terms of theatrical approach and of research. Depending on the topic, we usually conduct parallel interviews with witnesses of the time we are researching, as well as with relevant experts. We go to city archives and libraries and other institutions and look for documents, read newspapers from that time and discover traces of intimate histories, photos, objects, places… It is an endless field of research.

For example, when we were working on Between the Walls with the GLLUGL Association from Varaždin, we dealt with the Second World War and the Independent State of Croatia, and in the attic of the actors’ family house we found a brochure for a pharmacy product from 1941 and inserted it into the dialogue. From small details, such as a film that is mentioned in the piece that ran on the very day the action takes place, to very important information such as the names of the Holocaust victims and their addresses; it is essential to me that everything is authentic. Especially with respect to historically important topics and people’s biographies.

Of course, I am aware that by choosing the information I shape the narrative, but on the other hand, I present it to the audience in a very open way, so that it becomes clear how we selected the material and what is our position as authors.

All Adventurous Women Do at Atelje 212

Darija Davidović: In many of your interviews you refer to “us” in relation to your work. You depart from the conventional hierarchical order in theatre, which sees the director as the sole producer of a piece of art. This “us” also emphasizes the social and collective character of theatre. How important are these collective and social dimensions to your creative process?

Selma Spahić: To me, they are the most important. This is not always easy to put into practice, because the institutional theatre where I often work is based on hierarchy, but in essence, if we can work without hierarchy ever being felt, these are ideal theatre circumstances for me. I strongly believe in social communities, temporary and long-term ones, I believe in a group of people, and the theatre is a very powerful community during the process. It has the potential to be destructive, of course, but if you live those few months with enough openness and care, it can be like a small utopia.

Darija Davidović: You have worked with theatre institutions in Serbia, Croatia, Montenegro, Slovenia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as with actors from Kosovo – how important is transnational artistic cooperation in the post-Yugoslav space for you? How does such collaboration come about? Do you actively force “post-Yugoslav” artistic collaboration?

Selma Spahić: Co-productions, exchanges and collaborations were much more frequent when I started working outside of Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially in the beginning of 2010s. With the radicalization of nationalist politics and the severe cuts in cultural budgets, especially targeting those that do not suit the authorities, cultural politics changed as well, and many theatres became more closed. Of course, there are still theatres that are open to collaborative work, but there are fewer of them, and they face more difficulties in getting funding. For me, the exchange is quite natural, because I consider the entire former Yugoslavia as a common cultural space. It is natural for me that art has no borders, and that diversity enriches it. Some of the most important ensembles in the history of theatre were formed by people from all over the world. How can one do artistically relevant things if one is closed to diversity? It is completely pointless. It has never proven wrong for me, it has always been enriching, humanly and theatre-wise.

Darija Davidović: What you are currently working on? What are your upcoming projects?

Selma Spahić: We were just working on The Regression” by the British author Dennis Kelly at the Schauspiel Stuttgart. It is a thought experiment about how we should go back in our development, imagine a world without technology and think about where and how we as humankind have gone too far. The drama is very interesting because the movement, which succeeds at first, reaches its peak and then, like many movements and revolutions becomes extreme and leads to its complete opposite, totalitarianism, due to the human greed for power. The piece ends with faith in reason, faith in curiosity, in the ability of the human brain to discover and learn. It ends with some form of hope that means a lot in a time where everyday life warns us of the end of the world.

Main image: Dragan Mujan

Selma Spahic’s production of Tanja Šljivar’s All Adventurous Women Do will be presented at the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin, and is also a part of the main program of this year’s BITEF festival. Her devised production of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew will premiere in Kerempuh Theatre in Zagreb, Croatia, on 1st December 2023.

Further reading: review of Tanja Šljivar’s All Adventurous Women

Dr. Darija Davidović is based in Bern, Switzerland and Vienna, Austria. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the research project “Aestheticisation of war violence in contemporary performing Arts” at the Institute of Practices and Theories in the Arts, Bern Academy of the Arts. She obtained her doctoral degree from the University of Vienna, Department of Theatre, Film and Media Studies with her theses “Contested Wartime Past(s): practicing politics of history in Serbian and Croatian Contemporary Theater”, which will be published in 2024. She has been involved as activist in many feminist and antifascist projects and campaigns in Germany and Austria.