Darija Davidovic discusses the work of Roma theatre-maker Edis Galushi and the role theatre can play in addressing genocide, as a tool of remembrance and as an archive of social memory.

In his monodrama 02.08.1944, Edis Galushi tells the story of Roma victims during the Second World War II through the lens of one survivor. The title of his play refers to the day when 4300 children, sick and old people were murdered in the gas chambers at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp.

Only four victims survived the systematic extermination. Nowadays, the 2nd August marks the International Day of Remembrance of the Genocide of the Sinti and Roma, also known as Porajmos (the Devouring).

As a person interested in the history of the Second World War, I was aware of the crimes committed against Sinti and Roma, but until I watched Gashi’s monodrama, I was not aware of the fact that to this day there is no exact numbers of victims.

I was also not aware about the armed resistance against the oppressors at the Auschwitz-Birkenau Concentration Camp. On the 16th of May 1944, 600 Roma prisoners put up massive resistance against the SS guards, after they were warned that the Nazis were planning to execute them. Due to this massive resistance, no Roma prisoner was murdered in the gas chambers that day. The 16th May marks the Uprising of the Roma prisoners.

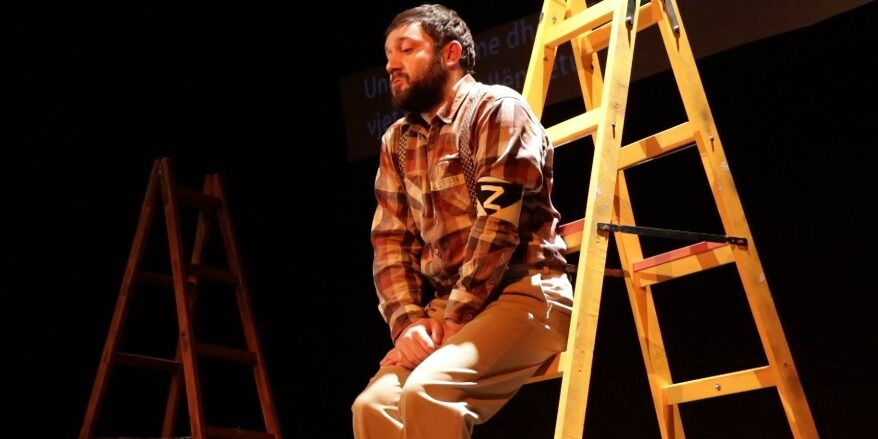

Edis Galushi in 02.08.1944

Edis Galushi is an artist, activist and professional translator of Romani language. He was born in 1989 and lives in Prizren, the second largest city in Kosovo, where he joined the Roma Theatre in Prizren at the age of 15. The monodrama 02.08.1944, in which Galushi plays the nameless survivor, is also performed in Romani and was premiered in January 2019 at the Bekim Fehmiu Theater in Prizren.

The monodrama tells the story of a former prisoner, the loss of his wife and son and the dehumanizing conditions in the camp. It interweaves fictional and documentary elements: Projected excerpts from a documentary film that chronologically reports on the persecution of the Sinti and Roma during World War II and Galushi’s artistic re-enactment together form the narrative framework of the monodrama. The performed memories of the main character not only take the audience back to 1944, but also provide insights into the intimate world of the protagonist’s thoughts and feelings.

Galushi first appears on a darkened stage with a suitcase in his hand, equipped only with a small wooden bench. In a kind of prologue, a visibly broken character enters the stage and states the reasons for the persecution of Roma at that time. These are the same prejudices that today still lead to discrimination and exclusion of Roma: “The reason they detained us here was that the word was spread all over the country that we are lazy, criminals and spies. In order to re-educate us, they decided to take us to the camp with ‘Arbeit macht frei’ written at its entrance”.

Watching Galushi’s play motivated me to take a look at the current German state of historical research about the Genocide of Roma. Critical voices in research emphasize that many important documents have not yet been evaluated, which would be important for processing the committed crimes.

These research gaps are attributed to an insufficient political reappraisal of the past in Germany. This leads to a lack of public recognition, which makes the official commemoration of Porajmos and the suffering of the Sinti and Roma as a central part of the German – or rather European – official culture of remembrance impossible. One consequence of this systematic forgetting is the lack of adequate reparations to the victims of the Holocaust, a critical approach to racism which is specifically directed against Sinti and Roma, and the long-lasting marginalization of Europe’s largest minority.

A comprehensive reappraisal would help to counteract exclusion and stigmatization by exposing historical continuities of this specific form of racism which Sinti and Roma have to face in their everyday life.

Plays like Galushi’s can have an enlightening function. They can provide an alternative to hegemonic interpretations of history. In playing a survivor and witness of the Genocide, the actor became a medium and the theatre becomes more than a space of artistic entertainment, it becomes an archive of forgotten memories and history from below.

This kind of theatre makes it possible for people to experience history in a creative and sensitive way. To make marginalized positions visible is the first step towards social and historical justice, the first step towards reclaiming the status of a social and historical subject. This first step of visibility can be achieved by means of art. In the context of marginalized history, theatre can make the past tangible:

Plays like 02.08.1944, which deal with the personal stories of survivors can give insight into hidden stories and historical crimes. In this sense, theatre functions as a memory machine, for memories which have been replaced in the collective memory or in the official culture of remembrance.

Galushi’s play is a good example of how theatre can be used as an archive of social memory and as a tool for mapping untold history. But also, as a way of conveying justice and raising awareness of historical events which affect current socio-political conditions.

This mechanism of social memory is present in oral poetry, storytelling and literature. But, in my opinion, theatre is particularly well-suited to this due to its multi-layered forms of communication and its different artistic approaches.

Could theatre be used as a kind of memory activism? The culture of remembrance functions as an important political tool, which in many cases preserves power and promotes political agendas. The institutional memorialization of the suffering of Sinti and Roma during the Second World reveals a significant lack of global memory dynamics. It even took Germany (the so-called “world champion of memorialization”) until 2012 to open the first memorial for Sinti and Roma. But this monument was recently in danger of being destroyed by construction work of the Deutsche Bahn. Finally, a compromise was reached in 2021 with the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma and Deutsche Bahn assured to protect the monument.

Berlin Sinta and Roma memorial. Photo: Mike Peel

Whether people participating in state commemoration events, visiting memorial centers, museums or participate in other forms of memorialization are aware of it or not, they are confronted with a specific image of the past, worldview and social value system. This is certainly the case in the countries of the former Yugoslavia – where history was often contested and revisionist interpretations of the past were used for propaganda and the basis of wars. The social values and views of the past conveyed during official state commemorative events often do not accelerate reconciliation and recognition of all war victims, which would be essential for a stable coexistence of different ethnic groups in the region of former Yugoslavia. State commemorative events often convey only one-sided perspectives of the wars, creating an image of the past in which the suffering of other ethnic groups does not exist – as if there were only one category of victims. The glorification of war crimes and war criminals in the region of former Yugoslavia influences the view of the past and the current discourse on the wars.

With the state commemoration of the NATO bombing, the Serbian government fulfils its duty to remember and honour the victims. However, if the historical context remains unmentioned and the only responsibility for the bombing is laid at the “great powers who attacked a small country”, the Serbian state does not fulfil its duty – especially towards the young generation – to educate about the senselessness of war and about the danger posed by racism and xenophobia. The state also does not fulfil its duty to remember and honuor victims of other ethnic groups.

On the 4th August in Bosnia and Herzegovina “the victory in the heroic battle to defend the Serb villages Vojkovići, Krupac and Grlica against the attacks of the Muslim units'” is celebrated while on the same day the defence of the city of Sarajevo is commemorated.

When in Croatia, in the context of the commemoration of the military operation Oluja, they celebrate the military victory rather than the end of the war, a fatal message is conveyed: the meaningfulness of war. It is important not to forget, that during this military operation 150,000-200,000 Serbian civilians were displaced and several hundred were murdered. The consequences of this kind of remembrance of the “Croatian Victory” are ongoing political tensions and public hostility: Belgrade accuses Zagreb of “celebrating over the graves” of Serbs and Croatia emphasizes the celebratory character of this military operation.

When contested memories and competing victim narratives are manipulated for political gain, reconciliation or stabilization can seem out of reach. However the work of numerous activists from this region gives us hope. They who are specifically engaged in memory activism in order to stand up for social as well as historical justice, but also against nationalism and the political instrumentalization of war victims.

The practices of memorialization as well as the practices of counter-hegemonic storytelling need to be reclaimed by the people as social and political tool of resistance.

The culture of remembrance can be considered a social and political arena of action in which everyone can participate by creating an alternative civic culture of remembrance. Activists in this field include the Women in Black Belgrade, members of the Antifascist League of the Republic of Croatia, who commemorate Croatian Serbs who lost their lives during the war in Croatia, Documenta Zagreb and the Reconciliation Network RECOM, which both as shed light on forgotten war crimes as does the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights Serbia.

This last group produced Zlatko Pakovic’s play Srebrenica. Kad mi ubijeni ustanemo/ When we murdered rise. In this play, Paković explores the ideological assumptions surrounding the genocide in Srebrenica. The focus of the play is the Serbian elite and their responsibility for the Genocide. In addition, the play creates arcs between the past war and the present sociopolitical conditions by drawing attention to the continuity of racism and hate. It also addresses the Greater Serbian ideology and how it contributed to the genocide in Srebrenica- a topic which has been neglected in local as well as international debates about the war crime.

Zlatko Paković’s Srebrenica. When We, the Murdered, Rise Up

Paković’s play suggests new ways of approaching the Genocide apart from the never-ending repetition and false assumption of collective guilt, used by Serbian politicians as the main argument against an official recognition of the war crime as Genocide.

Staged in 2015, Oliver Frljić’s play Aleksandra Zec deals with the murder of the Serbian Zec family, which took place in Zagreb in December 1991 a few months after the beginning of the Croatian war. Frljić constructs his own version of the historical crime, based on the court records and testimonies of the perpetrators. The testimonies of perpetrators are problematic documents, which can be obstructive in terms of establishing the truth. Frljić uses them as evidence of the impact of Tudjman’s xenophobic politics and provides insights into patterns of the perpetrators’ thoughts shaped by the ethnonationalist ideology.

Dah Theater from Serbia – a group which has produced many performances about the wars in Yugoslavia over its 30 year history –staged the play Crossing the line in 2009, a performance based on war testimonies of women from Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia. These theatrical testimonies of marginalized war experiences give us an insight into the brutal and patriarchal character of war. But they also enable us to recognize female solidarity during the war: In one scene, a woman in Vukovar is mourning the loss of a Serbian woman. In another scene a Serbian woman defends a Kosovo Albanian woman from the brutal treatment of a Serbian policeman during the war in Kosovo in 1999. All this is based on the testimonies of survivors.

There are many examples of this kind of performance in Kosovo. Examination, which was first performed in 2013 by the group HaveIt in order to support women who suffered sexual violence during the war. The 2012 play Valley of her Suffering directed by Zana Hoxha Krasniqi is also based on the testimonies of female survivors of the war in Kosovo.

There are currently around 12 million Sinti and Roma living in Europe, in most countries under precarious living conditions. During the Second World War, prejudices against them, which are still prevalent today, led to their expulsion and extermination. Understanding their history as part of European history and integrating their memories into the collective memory can be, at least symbolically, a first step in advocating for change of their living conditions and Galushi’s play achieves this in a creative, artistic way.

Theatre – especially theatre dealing with the topic of war – is never just an aesthetic object, but also a performative process. It makes the spectators witnesses both of the performance and of the staged history from below. When actors perform testimonies of wars, they become mediators of history – a kind of vicarious witness. They lend their bodies and voices to the survivors. They communicate with the audience and, we, the audience become a community. We became aware of the hidden history, of the historical crimes and of destructive human activities motivated by inhuman ideologies.

Theatre can be an archive of social memory, a tool for mapping history from below and forgotten memories. It can be a tool for reconciliation, a way in which we can come to understand others’ suffering – and each other in our everyday lives.

Dr. Darija Davidović is based in Bern, Switzerland and Vienna, Austria. She is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the research project “Aestheticisation of war violence in contemporary performing Arts” at the Institute of Practices and Theories in the Arts, Bern Academy of the Arts. She obtained her doctoral degree from the University of Vienna, Department of Theatre, Film and Media Studies with her theses “Contested Wartime Past(s): practicing politics of history in Serbian and Croatian Contemporary Theater”, which will be published in 2024. She has been involved as activist in many feminist and antifascist projects and campaigns in Germany and Austria.