Curator and critic Tamás Jászay provides an insider’s view on the 6th edition of dunaPart, the Hungarian independent performing arts showcase which took place in November 2023.

First held in 2008, dunaPart is the oldest continuously running showcase in the Hungarian performing arts scene. Organised by default every two years, but most recently after a four-year break due to the pandemic, the event’s primary, but not exclusive, focus is on presenting Hungarian independent theatre and contemporary dance to the performing arts community abroad, selected by a curatorial team that changes each time.

Programmers, directors of festivals and receptive venues, critics, journalists, cultural managers are invited to dunaPart. The aim is multifaceted. The most important is to promote Hungarian performing arts abroad, to nurture existing professional relationships and to establish new ones, in short, to internationalise Hungarian performing arts. Another important aim is to present the current tendencies of Hungarian independent theatre and contemporary dance, to provide a selected panorama for foreigners interested in the state of the scene. dunaPart also aims to answer the question of whether the theatre and dance of a small country can contribute to, challenge or even compete with European or global tendencies.

dunaPart is not a generously funded state initiative, but the heroic undertaking of a small team, constantly struggling with the insecurity of existence, which gains its real strength from the feedback of our foreign colleagues. It must be strange to read all this, as Hungary is a theatre powerhouse, certainly in statistical terms. We cannot name another country in the region where, before the pandemic, there were regularly more than 8 million (!) theatre tickets sold per nearly ten million inhabitants. Although the pandemic broke the momentum, the figures for 2022 are back close to 7 million tickets sold.

Before anyone misunderstands, this does not mean that the population of Hungary is sitting in the theatre day and night; declining state subsidies (mainly, but not exclusively, for independents) and rising overheads have disproportionately increased theatre ticket prices (too) in recent years, increasingly allowing a shrinking, well-off elite into the theatre auditorium – and the process is not over. However, my personal experience is that Hungarian theatre has a good reputation abroad: since the 2000s, we can name a number of Hungarian artists whose work has been watched with interest in many parts of Europe.

Helga Llazar – It Depends. Photo: Arpad Koles

But what does all this have to do with dunaPart? In the light of the above, it is difficult to understand why the cultural government does not strive to organise one, or rather several, well-funded showcases, i.e. to provide an opportunity for Hungarian theatre culture, which tends to be closed, to have a chance on the international stage. (Only rarely do directors from abroad direct in Hungarian theatres, and then only in the biggest venues – in this respect, Hungarian-language theatres in neighbouring countries, especially Romania and Serbia, where multilingualism and interculturalism are part of everyday life, are performing much better.) While the right-wing government in power in Hungary since 2010 has been preaching about national image, theatres, especially independent theatres, are at the bottom of the food chain in cultural policy.

The dunaPart is an event managed by Trafó – House of Contemporary Arts, which has been running since its inception in 2008 with minimal state support, a lot of volunteer work and minimal remuneration for the contributors. I welcome the fact that, in the interests of transparent communication, the organisers have published the income and expenditure figures for the 2023 showcase.

Numbers are impressive: thirty-five programmes took place in twelve venues over four days at the 2023 dunaPart, which – not counting the voluntary work of Trafó staff – was realised with a total budget of around 18 million HUF (46,000 EUR). Let me quote the classic: not great, not terrible. The Hungarian government proudly claims that Hungary is the country that spends the most on culture in Europe. If we add to this figure the guaranteed HUF 200 million (EUR 517,000) per year for MITEM, the international theatre festival organised by the National Theatre, which is also the institution’s own showcase, or the targeted state support for the Theatre Olympics (HUF 4 billion, or EUR 10.3 million!), also organised by the National Theatre in 2023, it becomes clear where dunaPart belongs next to the big, representative events. The message is clear: grassroots, low-budget initiatives like dunaPart do not stand a chance in the state-supported Hungarian performing arts ecosystem.

All this is absurd because many of the Hungarian directors who have appeared on the international scene, and practically all of the choreographers, have come from the independent scene. In the 2000s, the Hungarian and later international premieres and co-productions of three Hungarian directors in their thirties, Árpád Schilling, Viktor Bodó and Kornél Mundruczó, created and maintained a strong interest in Hungarian theatre abroad. Among the theatre artists who have had opportunities abroad in recent years are Béla Pintér (Béla Pintér and Company), Tamás Ördög (dollardaddy’s), Zoltán Balázs (Maladype Theatre) and Martin Boross (Stereo Akt), and from the field of contemporary dance Adrienn Hód (Hodworks), Máté Mészáros, Imre Vass and Zsuzsa Rózsavölgyi.

All these names have something in common: over the years, several of their works have been featured in previous editions of dunaPart. Of course, the link between a showcase and an invitation to a festival or co-production is not always obvious. Yet it is safe to say that dunaPart, with its extremely modest resources, has alone done more to promote and recognise Hungarian contemporary theatre culture abroad than any right-wing cultural government has ever done.

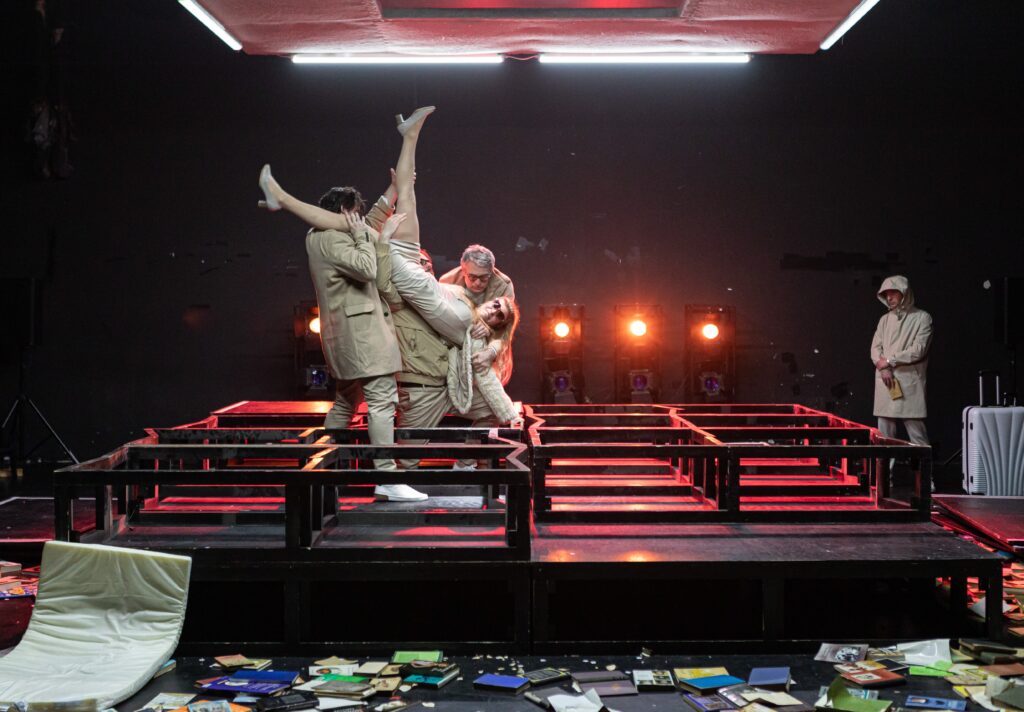

Orkeny Tteatre. Photo: Judit Horvath

It may be a coincidence, but the fact is that dunaPart was founded and the new Performing Arts Act was adopted in the same year, 2008. Perhaps the founders were naively hoping that the fixed amount of state subsidy guaranteed to independents in the law would usher in a new golden age, meaning that it was time to showcase the most exciting theatre and dance initiatives to the world in an organised way. Everyone was disappointed, as a process was about to begin that is now coming to an end: the bleeding of independents, i.e. the complete withdrawal of state subsidy, is still underway. ( For a description of the stages of this process up to 2013, see my article Finita la Commedia: The Debilitation of Hungarian Independent Theatre on Critical Stages. The reasons for the right-wing government’s aversion to critical culture are not covered here, but for those interested in the systematic dismantling of culture, education, science and the arts in Hungary in the 2010s and 2020s, I recommend the first and second editions of Hungary Turns its Back on Europe).

But now back to dunaPart: the 2023 edition, the sixth (actually the seventh including the 2013 Hungarian Showcase), was special in many ways. The showcase, originally scheduled for 2021, was cancelled by the pandemic, so the six curators invited by the organisers had to choose from four (!) years’ worth of performances instead of the usual two. The selection team was made up of practitioners and theoreticians, curators familiar with both Hungarian and international tendencies in contemporary theatre and dance. The challenge was a new but enjoyable one, to reconcile the very different curatorial perspectives, while the aim was to select around twenty productions, roughly half and half theatre and dance, that would be of interest to foreign audiences. The selection was based on around 200 (!) applications received in response to dunaPart’s public call for submissions. The methodology and rationale for the selection was described in the curatorial foreword published last summer.

It was our early realisation that after four years of hiatus and nearly a decade and a half of systematic government destruction of the Hungarian independent performing arts scene, the stakes of our selection are higher than ever. Many may have been surprised to see that the 2023 programme was filled almost exclusively with new names, rather than the usual suspects. This was not a decision: we realised during the selection process that a young and emerging generation with a strong voice has now appeared, and this is perhaps their first and last chance to step onto the international stage. At the same time, we considered that the aforementioned artists discovered in previous editions of dunaPart have now acquired the international networking capital necessary for their further development. The exception to this rule is mainly in the field of contemporary dance: Adrienn Hód or Máté Mészáros again submitted works that could not be refused.

What characterises this new generation? Due to the funding anomalies of the 2010s, the majority of independent theatre companies in Hungary have now disappeared. This does not mean that new productions are not being created: however, project-based operations are much more prevalent than before. There has been a marked increase in productions with a few performers and minimal scenery, usually literally inviting the audience into intimate proximity. My personal favourite of these is László Göndör’s one-man show, Living the Dream with Grandma, which makes us laugh and reflect on the past, private history and the coexistence of generations in the context of one of the greatest taboos, the Holocaust.

Narrative Collective. Photo: Daniel Domolky

There has been a proliferation of devised performances, which is worth noting because Hungarian theatre traditionally adds to the range of classical, drama-based theatre cultures. This is why we thought it important to give space to performances based on the dramatic canon rather than on original experience. A new performance of Henrik Ibsen’s Solness focuses on the impossibility of generational change and physical and psychological abuse, was staged in the studio of Örkény Theatre, one of Budapest’s leading theatres (director: Ildikó Gáspár). The Narrative Collective, which was formed a few years ago and is now on the verge of dissolution premiered Demerung after Chekhov’s Cherry Orchard: a group of young actors speak with verve about the problems that are pressing them (directed by Máté Hegymegi and Dániel D. Kovács). A co-production between the Jókai Theatre in Komárno (Slovakia) and the Szkéné Theatre in Budapest sweeps up the myths of Don Juan in a spectacular performance that mobilises great acting energy (director: Péter István Nagy).

In the theatre, it is striking to see productions that cross boundaries, be it genre, aesthetic or otherwise. Grotesque Gymnastics’ The Anatomy of Failure reflects on the notions of failure, struggle and success through the intense use of well-trained bodies. In more ways than one, Lili Horvát’s Dichterliebe – The 12 Giants is a transgressive project: the filmmaker’s first theatrical production mixes Schumann’s song cycle with film, live symphony orchestra and singing, creating a truly Gesamtkunstwerk. An installation based on the Örkény Theatre’s Winterreise, winterreise.box (concept: Botond Devich, Jakab Tarnóczi), which won a prize at the Prague Quadrennial, deconstructs Schubert’s music among the props of life in a dilapidated apartment. The intersection of puppet, theatre and dance featured several performances: Domokos Kovács’ reburn a cathedral drew attention to the importance of ecological thinking, while Helga Lázár’s It depends, a solo composed for her own body and a full-figure puppet, was a real experimental work.

Ever since the power ruthlessly seized the University of Theatre and Film Arts in Budapest under the pretext of the so-called model change, a parallel “partisan structure” called Freeszfe has emerged for the students and teachers who left the institution. Two of the performances of the virtual institution’s performance class have been included in the arts programme. In God, Home, Kitchen, Mikolt Tózsa reports through a personal filter on the life of a young woman during the Christian-conservative political course. Richárd Melykó presents an ironic and interactive lecture performance in Mass Orbit, enriching the series of conceptual performances.

I am primarily a theatre critic, and painful as it is to say, the real progression in Hungarian performing arts has clearly been in the field of contemporary dance for some time. I will mention just a few of the many possible reasons. Contemporary dance, as a primarily non-verbal field, has never been able to attract the attention of the politicians, although conservative decision makers should be aware that the politics of the body carries much more serious messages than the direct politicisation they dread. There are no companies in contemporary dance (the exception to this rule is Hodworks, led by Adrienn Hód), with only occasional collaborations that, given the right chemistry, are repeated. This is also linked to dance’s strong international embeddedness: it is as if the easily travelled productions of contemporary dance artists have the international safety net – in the form of residencies, workshops, festivals and platforms – that theatre companies can only dream of.

As an outsider who is curious about the world of contemporary dance, I have nevertheless identified a few characteristic trends. A recurring theme was burnout, fatigue, the depletion of creative energy, the most beautiful example of which was Viktor Szeri’s one-man performance fatigue. AHA Collective is an important fresh team in the non-hierarchical collaboration that is becoming increasingly common in dance: their debut performance Dense Piece creates moments of real tension with its minimalist, repetitive, disturbingly distinctive physicality. Jenna Jalonen and SUB.LAB.PRO’s Ring, a performance that enters into dialogue with tradition, is memorable for its clean beauty and its creative and ceaseless reinterpretation of the circular form. Tímea Kovács and Kinga Ötvös’s joint project in resonance, which also reflects on the possibilities of contemporary rhetoric, has a different hypnotic power. Pure dance is Réka Oberfrank’s Miracle, a performance that reflects on the relationship between the individual and the multitude, using the language of the body.

A particularly exciting group of dance performances were those that reflected on the concept of the body through darkness, light, non-normative approaches, or even through the chaos of contemporary reality. In in_form, Imre Vass conducts a fitness class in total darkness, sharpening the viewer’s vision and hearing in an unconventional way. Máté Mészáros’s communal coexistence entitled Through Light meditates on the mutually conditional relationship between light and darkness. In Deep fake, Gergő D. Farkas reflects on simulation, reality and the position of the human being in it, in the context of gamer culture. Júlia Vavra’s performance Artists like me is an irony on the institutional system and functioning mechanisms of the contemporary art world.

A divisive, provocative and taboo-breaking production, Idol is a co-production of Hodworks and ArtMenők. It is a challenge for choreographer Adrienn Hód and for the audience, used to normative bodies, to observe the cooperation of the multiply disabled and the healthy dancers: the structure is based on solid foundations and is vibrantly present throughout with chance and unpredictability. Game Changer, by the trio of Csaba Molnár, Imre Vass, Zsófia Tamara Vadas, is a very different provocation, but for the open-minded viewer a similarly liberating experience, closely linked to the aforementioned theme of artistic burnout. The three performers trace their activities back to the very foundations of the theatrical situation, questioning and scrutinising everything from where it is possible to build at all. They do so self-reflexively and self-deprecatingly, with plenty of humour and originality. As if to say: after everything around us has been destroyed, it is time to start building again.

For further information, visit: dunapart.net

Further reading: Singing Youth: “Political systems embedded in culture are here to stay”

Jászay Tamas is a theatre critic, editor, university lecturer, and curator. Since 2003 he's been working as a freelance theatre critic: in the last 20 years he published more than 1200 articles (mostly reviews) in more than 20 magazines all around the world. Since 2008 he is co-editor, since 2021 editor-in-chief of the critical portal, Revizor (www.revizoronline.com). Between 2009 and 2016 he was working as the co-president of the Hungarian Theatre Critics' Association. In 2013 he defended his PhD thesis on the history of Krétakör Theatre (Chalk Circle Theatre). He regularly works as a curator too: Hungarian Showcase (Budapest, 2013), Szene Ungarn (Vienna, 2013), THEALTER Festival (Szeged, since 2014), dunaPart (Budapest, 2015, 2017, 2019, 2023). Since 2015 he's been teaching at Szeged University, since 2019 as an assistant professor.