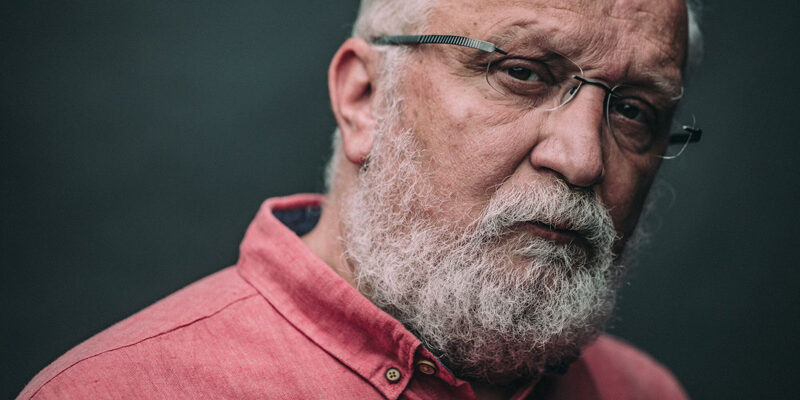

Photo: Primož Korošec

Before his production of Miss Julie opened in Belgrade last month, it had been 30 years since renowned director Haris Pašović last worked in the city. Borisav Matić speaks to him about his new production of Strindberg’s play and his long and eventful career.

The career of Haris Pašović, the theatre director and multidisciplinary artist from Bosnia and Herzegovina, has been so rich, long-lasting and socially aware that we could easily trace through his work the history of life in South-Eastern Europe during the last few decades.

During the 1980s, his performances have become landmarks of Yugoslav, culture like the Spring Awakening at Yugoslav Drama Theatre in 1987. Pašović, who was 26 at the time, directed Frank Wedekind’s classical play about young people whose vitality is killed by their conservative parents and repressive institutions. From today’s point of view, the performance could be interpreted as an ominous – although perhaps an unintentional – sign of the horrors young people would experience several years later during the war.

His production of Waiting for Godot at Belgrade Drama Theatre premiered on 25th June 1991. It wasn’t just the last performance Pašović directed in Belgrade before the catastrophe war, but also, as he puts it, it was the last performance in Yugoslavia. “During the break, after the first act, someone passed by and said that the tanks were heading to Slovenia. Thus, we played the first act in the SFRY, and the second practically in disintegrated Yugoslavia.”

Miss Julie at the Madlenianum Theatre. Photo: Zoran Škrbić

But the Yugoslav wars did not suppressed Pašović’s artistic works– on the contrary. During the three-and-a-half-year siege of Sarajevo, he managed the MESS International Theatre Festival which was one of the biggest Yugoslav festivals, and also continues to be an important factor of intercultural exchange in the region to this day. To fight isolation during the siege, he also founded the Sarajevo Film Festival which has grown to a very important European festival.

After the war, Pašović continued to fight for tolerance and unity in the region, directing Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet at MESS, a spectacle played in front of the Parliament with 25 actors, 60 crew members and heavy war machinery. But most importantly, the plot revolved around a Muslim Romeo and Christian Juliet. And in 2012 he made an installation “Sarajevo Red Line“, an 825-meter long artwork made of chairs that commemorated the 20th anniversary of the siege and its 11 541 victims – each red chair for each victim.

But now the times have changed and the war traumas of the region slowly begin to heal while new, economic inequalities are emerging visible in the divide between the European Union (Slovenia and Croatia) and the so-called Western Balkans. Thirty years after his last performance in Belgrade, Pašović finally directed again in the city, this time at the Madlenianum theatre.

I asked Pašović about his new production of August Strindberg’s Miss Julie which has a contemporary setting and deals with the inequality in the region. In this adaptation, Miss Julie is Slovenian from a rich family, while her servant Jean is a Serbian earning for life at her father’s estate.

The last performance you directed in Belgrade, Waiting for Godot at Belgrade Drama Theatre, coincided with the beginning of war in Yugoslavia. Does Miss Julie which thematizes Slovenian-Serbian and other ex-Yu relations witness that we are still in a whirlwind of regional inequality and intolerance 30 years later?

Our Miss Julie is about a completely different reality. The focus is on the individual and his or her inner world; consciousness and subconsciousness; ambition; survival in a cruel environment. In social, economic and political terms, this performance is also completely new. This is by no means an ex-Yugoslav performance, nor is it post-Yugoslav. This performance has nothing to do with Yugoslavia. “New reality” in South-Eastern Europe is no longer new. Actors who play in this performance are younger than thirty and were born in a completely different Europe than the one I was born in. I completely understand that young generations are tired of this Yugoslav story. I’m tired too. I don’t want to be a victim of the past, nor nostalgic. I’m completely in the present moment and looking to the future.

Europe today is a Europe of inequality, and that is especially expressed in relation to the so-called Western Balkans. Tens of thousands of young Balkans go to the EU for economic reasons and do the hardest physical work there. They are becoming a new social class, the lowest in the European social hierarchy. How to build a life in such a Europe? – that is the question of today.

Miss Julie at the Madlenianum Theatre. Photo: Zoran Škrbić

In your performance, the relationship between Miss Julie, a daughter of a Slovenian mogul, and her Serbian servant could be interpreted through the feeling of superiority that exists in one part of Slovenian society towards the rest of the Balkans and envy of Serbian society towards the economically more developed Slovenia. What made you to actualize Strindberg’s play in this way?

This element can also be felt occasionally in the performance, although that is not the topic. This is a consequence of certain stereotypes that exist on both the Slovenian and Western Balkan sides. I am not subject to stereotypes. I know Serbia and Slovenia well, I have many friends and acquaintances in both countries, I often stay and work in both countries. Real life is always much more complex and much more interesting than stereotypes. It’s enough to remind of the obvious – Slovenians love coming to Serbia, especially to Belgrade, to have a good time and eat well; Serbs value Slovenian diligence and care for the environment… At the same time, even today it can often be seen that Bosnians, Serbs and Macedonians are separated at the Slovenian border and subject to long checks, and are exposed to an unkind attitude of Slovenian border guards.

In addition to nationality, class plays a large role in your direction of Miss Julie, almost as much as in the play. Is this an expression of your position that the relationship between socioeconomic classes has not changed substantially from Strindberg’s period until today?

Along with the theme of the inner individual world, the class relationship is the main theme of the performance. Strindberg ingeniously linked the two themes even before Freud began to develop psychoanalysis. Miss Julie is as relevant today as it was 150 years ago because nothing has essentially changed, as you said. It is even more relevant with us, because we again live in a class society, and that doesn’t seem to be clear yet. Neither politics, nor art, nor science, nor the media talk about that here; that new class reality is completely kept silent. We are talking about rich people, but in the sense of “that obscure object of desire”, as the great director, Luis Bunuel would say, and not in sense of social relations. We don’t talk about poverty. It is present indirectly in the public. It is shyly indicated when it’s necessary to raise money for someone’s treatment or through some other, most often humanitarian, aspect. Class consciousness doesn’t exist.

Even the mention of class consciousness is associated with communism and is considered something outdated, almost shameful. This is a very interesting phenomenon; the total victory of neoliberal capitalism, which declared even the thought of class consciousness regressive, old-fashioned, in fact, stupid.

At the same time, the class gap is rapidly widening. Nouveau riche are getting richer every day and the middle class is getting dramatically impoverished. Insurmountable class differences are being created between the super-rich and the poor, and this affects young people the most. When the status of non-EU citizens (like some lower-class people) is added to those poor, we get a deep injustice.

You directed Spring Awakening at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre in the 1980s, a performance where young characters end tragically due to repression coming from institutions like school, church and family. And today in your Miss Julie, characters also suffer because of their family or environment. Are these similarities the product of classical plays you chose to direct, or, just like with the class issue, has the repressive attitude towards young people not changed?

That repressive attitude has not changed. Authoritarian structures – family, school, politics, religion – slowly change, and young people are still victims of that authoritarianism as they have been for the last 150 years. I remember being terribly struck by something I found during my research for directing Spring Awakening. It was the case of a fourteen-year-old girl who killed herself and tattooed a farewell message on her forearm and it read: “I can’t anymore!” Even today, young people are struggling with the repression of the environment. This sometimes results in resignation and a sense of nihilism, sometimes most tragically – with suicide, and some manage to win and break free. I know that it is necessary to fight. No one is allowed to take my life, my time, my energy. When I start to lose strength and will, I stand in front of the mirror, slap myself and say “You will not give up! Fight!”

Miss Julie at the Madlenianum Theatre. Photo: Zoran Škrbić

You worked on Miss Julie with actors from various parts of former Yugoslavia. Do they have different acting and artistic approaches to the theatre or can it be said that we belong to the same cultural field in that respect?

This multiculturalism of the project happened almost by accident. I made the acting cast and the collaborative team with Ana Zdravković Radivojević, the director of Drama at Madlenianum theatre. It was natural for actors from Belgrade to play. Strahinja Blažić was a perfect choice for the lead role of the servant Jean. Following my idea that the plot takes place at the property of a Slovenian mogul, we came to Sara Dirnbek, a Slovenian actress who plays the second leading role, Julie. Mina Pavlica is from Novi Sad, I have already worked on two performances with her and I knew her fascinating potential. The other actors are from Belgrade and Novi Sad. I also invited Irma Saje and Vanja Ciraj, my longtime extraordinary collaborators from Sarajevo, to make costumes, and the brilliant Marko Grubić (music), Aleksandar Denić (scenography), Jelena Sinkević Paligorić (dramaturgy) and Igor Pastor (choreography) are from Belgrade. We all belong to the same cultural field, that is evident. Mentality, culture, language, humor, everything is the same for us. Even our flaws are the same (laugh).

How much did working on a regional project like Miss Julie mean to you in times of uncertainty and reduced intercultural interactions because of the pandemic?

I’m working my whole life like this, this is natural to me. I traveled during the pandemic, everything can be overcome with a smart approach. Madlenianum had the courage to take the risk in that sense with Miss Julie, and it paid off. The result is that we worked well, got a good performance, encouraged both ourselves and the audience. Theatre is, indeed, a wonderful art!

Borisav Matić is a critic and dramaturg from Serbia. He is the Regional Managing Editor at The Theatre Times. He regularly writes about theatre for a range of publications and media.

He’s a member of the feminist collective Rebel Readers with whom he co-edits Bookvica, their platform for literary criticism, and produces literary shows and podcasts. He occasionally works as a dramaturg or a scriptwriter for theatre, TV, radio and other media. He's the administrator of IDEA - the International Drama/Theatre and Education Association.