Goran Injac, artistic director of Mladinsko Theatre, talks to Nick Awde about making socio-politically engaged theatre, Slovenia’s post-Yugoslav cultural legacy and how he views the role of the artistic director.

Artistic directors come in many shapes and forms. There’s a broad spectrum to the role which involves the managing of a theatre’s programme, one that stretches from purely administrative to purely creative – and a theatre’s artistic output will reflect this.

The Mladinsko Theatre in Ljubljana started life in the 1950s as a communist state theatre for the young (Mladinsko = Youth) but turned in a more adult political direction in the 1980s, a path that it continues down in the 21st century under the guidance of artistic director Goran Injac, who has been in the role since 2014.

So, in this day and age of targets and outcomes, what ‘added value’ does an artistic director bring to theatre? Injac has some thoughts: “Most directors at a theatre are basically there to deal with the administrative staff while the programme takes care of itself,” he says. You bring in a string of directors or productions and that’s it. You mostly aim for people who have the profile which you decide that your audience is looking for. On the other hand if you want to have a programme that is artistically and politically relevant, you should ask yourself what is the theatre that you are making for, what role will your theatre have in your society?”

Every country or region seems to have its own priorities when appointing artistic directors. In some cases they are stage directors who direct their own shows; in other cases they are creative administrators who get the right people in the room, or perhaps they are seasoned actors.

The latter scenario is very much a feature of the post-Yugoslav space, observes Injac. “We inherited this from Yugoslavia, where it was common to have actors as artistic directors or directors of theatres. On the other hand, in somewhere like Germany an artistic director actor is impossible to find – nobody would even apply. So it shows the different ways theatre is seen, where the most visible figure in a theatre is connected to the commercial side. If you appoint a well-known actor as your artistic director, it has a corresponding commercial impact.”

Injac draws on his own perspective as a dramaturg/curator, a rare confluence that makes the Mladinsko one of the only theatres in the post-Yugoslav space that places dramaturgy in the creative driving seat. “I’m not interested so much in a theatre but more in the power that theatre has as a political and social event. Using targeted programming and creating a whole referential frame around productions, I’m always looking for ways to initiate a public debate that enters the wider social space, because all the critiques, reviews, political reactions, attacks, agreements, disagreements are an integral part of the performance. It’s not just what we’re performing on the stage, it’s also about the impact that we have afterwards. If you curate a wider public or political event beyond the production, then that is also a theatre event.”

Many theatres across Europe aspire to this line of socio-political effect – or claim they do – but it’s not as easy as it looks. You can push the politics into the programme but how you do it successfully is related to how the theatre is structured and the way it sits within its society. “Mladinsko is a public theatre and therefore an upbearer of official culture,” Injac points out. “It adds to the challenge because we are not expected to be politically provocative or politically relevant. As an institution that is part of the system, we are expected to support the system.”

Mladinsko is 100% public funded, and public money means public responsibility. Of course public money can be used for commercial purposes but Injac takes a different view: “It’s a gift that should prioritise other things. What people tend not to understand is that art is always political even if we are not directly carrying out political activism or acts. You are advocating for a certain system of values, the art exists in public space, it demands reactions and opinions and so on. But, to use a word that’s deeply unpopular today and is usually associated with communism and Marxism, what most of the traditional, especially national houses are actually doing is reactionary programming.”

To make theatre that makes a difference you need start by carving out your position within your own society – and the role of curator-as-artistic-director opens up all sorts of possibilities. They create strong profiles, a notable example being Berlin’s Maxim Gorki Theater, where Şermin Langhoff works alongside joint artistic director Oliver Frljić (a regular collaborator with injac, appointed in 2022) with marginalised groups including migrants from the Turkish, ex-Yugoslav and Roma communities.

“I share that background,” says Injac, who is originally from Serbia, “so I especially appreciate the political effect of the dramaturgy side, how the Gorki creates a place for topics to be discussed that could not be discussed in other places. You do not have another theatre in Germany that deals at such a high profile with migrant issues. Other theatres do projects from time to time, but at the Gorki the whole programme is built around it.”

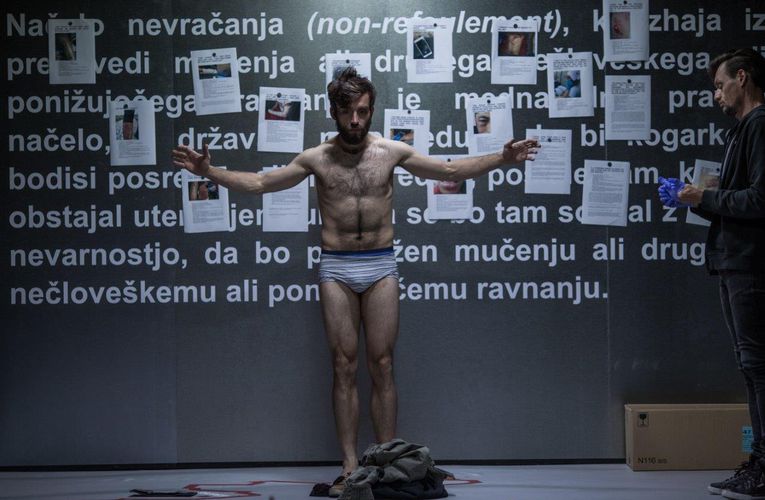

Gejm, Mladinsko Theatre. Photo: Matej Povse

Over in Belgium, NTGent has thrived on the stage director model. Milo Rau created a manifesto that tackles issues both in Belgium and beyond its borders. He has made connecting artistically with world events into a political choice, fusing these two sides in his shows and also allowing his personal style to react to and be moulded by the community. In NTGent’s case, it was the municipality that decided to reinvent their city’s approach to art and their invitation to Rau was to create a living consultation that asks what should a public theatre be and what should it do?

These different experiments in different places makes it challenging to compare their impact. “If you look at Poland, you’ll find a country where theatre is a big deal,” says Injac. “Working in theatre isn’t just a job, it is an important job. It is connected to the position that theatre has in society – is it a place where we discuss certain social issues or it is a place where we go to entertain? Here in Slovenia, it is a little bit different because we are still fighting all the time for more visibility and to show that theatre has a relevant voice.”

Think of Slovenia and the image that may pop up in your head is of heritage buildings, lakes, skiing and spas. Although not as wealthy as Germany, it’s evidently a country that supports its culture well – National Geographic hailed it in 2017 as the country with the world’s most sustainable tourism.

But Mladinsko’s theatre is not of that culture. “It is important for the state that culture provides a voice in public debate. You have culture for the elites and the tourists, but there’s also approach to the culture that the Yugoslav space has inherited from socialism, culture that is designed to give everybody access to it.”

Slovenia has preserved this infrastructure, largely because the country avoided the wars that the rest of the region suffered and the resulting internal collapse of their institutions. Slovenia has inherited not only a strong artistic system but also a physical one where every village has a cultural centre that is owned, run and funded by the state. “Mladinsko regularly tours this network as an inherited obligation and an inherited audience, and there is a normal expectation that we do it in these places, even with the cost cutting in the arts today. This notion of responsibility is important in how I make artistic choices and ask what is our aesthetic contribution to the wider theatre space beyond our own walls.”

Mladinsko’s focus is less on text-based projects and more on devised theatre, often mixing with visual arts, but whatever the genre, the shows are a platform for issues to be discussed. Devising is a particularly attractive tool for Injac because its collective process forces you “to examine your beliefs as an artist and a citizen because you need to discuss the issues that build the performance”.

Slovenia is a small nation which, while it has a different heritage, aspires to be Western European. “Slovenia is also a new nation so there is a positive discourse about state and society all the time because people are still happy to be in their own country and we do not have to be actually talking about others.”

Žiga Divjak is a young Slovenian director whose work at Mladinsko is known for its political engagement. His play 6 views the refugee crisis in the Balkans through the real-life experience of a group of six children accepted by Slovenia as a part of a quota that each country of European Union was supposed to adopt as an integration programme for refugees. The country took children from Afghanistan and Syria and placed them in a school in a small provincial town, a move that sparked protests from local parents. They didn’t want migrants to be in the same classroom as their children because they were “criminals” – just ten years old – who would corrupt their children.

It was a theatre first for Slovenia, which Divjak followed up with Gejm (The Game), about the pushbacks of migrants – the illegal but common practice where asylum is denied to migrants trying to enter the Schengen zone. Slovenian police catch migrants trying to cross the border, push them back to Croatia where the Croatian police beat and extort them before pushing them back to Bosnia, outside the European Union. As Injac recalls: “We did a lot of research and found their testimonies through the Border Violence Network, where we saw stories of people who have tried up to 40 times to make the crossing.”

A show that Injac is especially proud of is Republika Slovenija, staged by Mladinsko to coincide with the 25th anniversary of the country’s independence in 2016. “We made a partly verbatim piece set at the beginning of the conflicts in Yugoslavia in the 90s when the Slovenian government discussed selling weapons with Bosnia and Croatia who were at war. This was despite a ban by the United Nations on trading and selling arms to the warring sides, which means that Slovenia indirectly took part in all these wars by supplying one side or the other. TV crews from all over the region came for the premiere and there was even an after-show talk with Milan Kuča, Slovenia’s first president who was in power at the time.”

The Republic of Slovenia, Mladinsko Theatre

An artistic director under such circumstances also needs limitless reserves of diplomacy if they are to continue pushing the social envelope. Biting the hand that feeds you is one obvious risk for a state-funded theatre. Ultimately it’s your job on the line if you displease the powers that be and there are commercial consequences if the audiences don’t come.

There can be a level of personal risk too. “It’s a big question. When I did Klatwa (The Curse) with Oliver Frljić there were protests from groups like neo-nazis in Poland – it was an extremely dangerous situation for everyone. What we do in the Mladinsko is possible because there is a tradition of politically engaged art. Of course what was seen as politically engaged in the communist 70s and 80s is very different from today, but there is an unbroken tradition and it has opened up a side that is somewhat emancipated.”

Because Mladinsko is now expected to be provocative one way or another, there exists a higher political tolerance for its productions than is applied to other theatres. “If I did Republika Slovenija at the National Theatre I would have lost my job the next day and probably have to leave the country the day after.”

It doesn’t mean that Mladinsko is immune to attack. In fact it’s a regular occurrence and Injac’s position means that he is the first in line. “I’m seen as provocative because ‘he’s a non-Slovenian guy who is anti-Slovenian and he’s doing this intentionally because he does not know us but we’re not like that!’ The reality is that I am capable of living and working here because I believe theatre is important and that what we are doing and what we are supported to do has wider social and political importance.”

There exists a large section of the Slovenian art and political establishments who will step in to defend the theatre and support its artistic director, which helped Mladinsko to survive the two and a half years of right-wing populism that ruled the country during Covid and used the situation to undermine the theatre. “It was tricky what would happen with Mladinsko at that time because we came under pressure to conform,” observes Injac. “We succeeded in protecting ourselves because though we are funded by the ministry of culture, we are governed by the city – so the national government couldn’t change our theatre’s direction. It might seem as if we are on a battlefield all the time but the important thing will always be make it fun to create what happens on our stage.”

Main image: Borut Cvetko

For further information, visit: Mladinsko.com

Further reading: interview with Žiga Divjak: “We have to completely change our value system”

Nick Awde is a journalist, playwright, editor, critic and producer. Based in the UK, he is co-director of Morecambe's Alhambra Theatre. Books include Equal Stages (diversity and inclusion in theatre), Mellotron, Women In Islam, and translations of plays by other writers. Much of his work focuses on ethnoconflict and language/cultural genocide.