Slovensko mladinsko gledališče, premiere 10th June, 2020 (part of Mladinsko showcase 2022)

‘Pushback’ is a term that refers to refugees and migrants being forced back over a border without allowing them to claim asylum and often counter to the state’s official position on migrants. It’s a way of offloading people and avoiding responsibility. These policies create a kind of snakes and ladders with refugees making multiple attempts to evade the authorities and the often brutal methods used to return them.

Premiering in 2020, Žiga Divjak’s Gejm is based on testimony from the Border Violence Monitoring Network database, an organisation which documents the abuses faced by migrants crossing Europe. The show breaks things down case by case, using the statements of the refugees about the their treatment at the hands of the Slovenian and Croatian police, to paint an unbearable picture of a system that treats them as less than human.

Five performers – Primzo Bezjak, Sara Dirnbek, Marusa Oblak, Matej Puc, Vito Weis – take it in turns to recite statements from different migrants, each one prefaced by their ages and the violence and abuse they have faced. These quickly take on a grim familiarity. The migrants are stuffed into the back of windowless vans and subjected to either extreme heat or extreme cold. They are forced to sign papers in a language they don’t understand. They are told they cannot claim asylum, not here. They are not wanted in Slovenia. They are driven back across the border. The Croatian police often beat them. They have their money taken from them and their phones smashed in front of them. A Muslim woman has her scarf torn from her (“there are no Muslims here,” she is told forcefully). Their pleas for water, for food, for a translator, for someone to listen to them, go ignored; they are treated as a pest, something to be kept out at all costs, rather than human beings fleeing conflict and persecution.

The repetition soon comes to feel relentless, the same phrases recurring like a chorus. We soon see this to be a concerted campaign to purge Slovenia. Over and over we hear the same words: they beat us, they smashed our phones, they took our money, and while they were doing this, they laughed. (The laughter is somehow even more upsetting than the violence).

The outline of borders are marked out on the floor in tape. After the actors have calmly recited their stories they add an object to a growing college on the ground: tins of food, shoes, a broken phone, a jacket soaked in a bowl of water until it’s sopping wet.

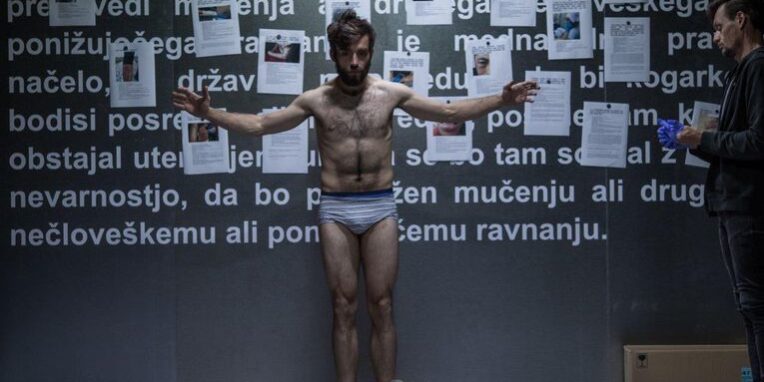

The relatively calm documentary style of the performance is punctuated with sudden bursts of violence and action. Rucksacks are emptied callously and carelessly, possessions splashing and smashing onto the floor. One actor attacks a chair with a baton, another bellows “go, go, go”, over and over. A phone is obliterated. The room is plunged into blackness and torch beams are shone in people’s faces. One of the performers takes off his clothes while another dons plastic gloves and roughly parts his buttocks.

Gejm, Mladinsko Theatre. Photo: Matej Povse

I’ve seen this piece before on video – it was live-streamed by Mladinsko during the pandemic – but the intimacy of the long narrow subterranean room adds considerably to the intensity. The space (set design by Igor Vasiljev) is bookended with a corrugated iron wall and a bunk bed; a cramped, make-shift space, not a place of comfort – above the bed there is a sign for the IOM (International Organization for Migration) with the EU flag prominent. On the other side of the narrow performance space, the actors staple up the witness statements, papering the wall with them. Divjak places his audience on the periphery, with the performers sitting among them when they are not speaking.

As a director, Divjak uses repetition and iteration to powerful effect. It is the similarity of the testimonies that gives them their cumulative power. In terms of form, this is documentary theatre concerned with the transmission of information, with lifting statistics of the page. The actors embody rather than enact the role of refugee. Western governments and certain western media outlets are adept at stripping refugees of their humanity. This show attempts to return it to them. Only at the end do we hear the voices of some of the people still stuck in this system, bounced around like pinballs. They talk about the lost time, the years spent stuck in the system, half-living.

In Ljubljana’s Museum of Modern Art Metalkova, there is currently an exhibition called If the Forests Could Talk, They Would Dry Up with Sadness which features a video of the barbed wire wall Slovenia erected at its southern border, the border to the Schengen zone, curl upon curl of silver, the barbs like vicious little leaves, nestled among the greenery. The contrast is quite breath-taking, it’s hard to imagine a more vivid symbol of the violence of borders.

Watching this piece now, in the light of the war in Ukraine and the level of welcome that has been extended to the millions of refugees by western Europe generates a queasy feeling at the double standards and the coded – and overt – racism.

The show ends with a list of those who did not survive, their bodies recovered from rivers or discovered dead from exhaustion and exposure. The ones unable to tell their stories. By the end of the feeling of sickness and fury is almost unbearable, at the plight of people reduced to playthings in a brutal, cruel game which we have enabled through indifference – and through silence.

Credits:

Director: Žiga Divjak

Research assistance: Maja Ava Žiberna

Drama collaborator: Katarina Morano

Set design: Igor Vasiljev

Costume design: Tina Pavlović

Music, sound and video design: Blaž Gracar

Lighting designer, technical director of the show and props: Igor Remeta

For tickets and further information, visit: Mladinsko.com

Further reading: review of Žiga Divjak’s Fever at Mladinsko Theatre

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0