Mladinsko Theatre and Maska Ljubljana, premiered 20th August 2021 (part of Mladinsko showcase 2022)

A man dressed in a Pink Panther costume is beckoning us. He curls his finger.

Come in, come in.

This is how it begins.

Nina Rajić Kranjac’s Solo is something more than a performance. It’s an experience. It’s a ride. It’s a feast. It’s a four-hour fuck-you to theatrical tidiness.

Some context: Nina Rajić Kranjac is a Slovenian theatre director. A successful and acclaimed one. She’s won a lot of prizes. She directed Lars von Trier’s The Idiots for the Mladinsko theatre, where we are now. Her CV is impressive. She’s relatively young – born in 1991, the year Slovenia became independent – so she’s achieved a lot in a short time. She’s also the performer of this piece, making what she claims to be her last show before she leaves theatre behind and moves on to new things.

In Solo, she puts herself on stage, in a show that is sort of about her as artist, but also about the pressure that everyone feels to hit milestones, to achieve, achieve, achieve. It’s about her, about Nina. But it’s also a show about theatre and the role of the director. It’s about being deemed a ‘success’ and what that feels like. It’s full of in-jokes about other notable Slovenian theatre makers – Žiga Divjak gets namechecked, they kvetch about some of choices made by the director of the current production of The Fig Tree at the National Theatre. It is self-exploratory and self-critiquing and self-indulgent yet, at the same time, it is also an intensely collaborative, intensely live experience, chaotic and ridiculous and beautiful and moving.

Over the space of four hours – it is listed as three and a half, but to end on time would have been out of keeping with the nature of the performance – Nina and her co-stars take the audience on a rambling, semi-improvised journey. It feels as if, structurally, there are some key lines and scenes they need to perform, beats they need to hit, cues they need to react to, but there’s also plenty of room for digression and mess. It’s as if these moments are pegs on a washing line with space in between for play.

Nina Rajić Kranjac’s Solo

This does not convey the sheer energy and sprawl of the piece. The actors sit on people’s laps, they dangle from the lighting rig. They wail and stamp like toddlers throwing a tantrum. They announce Nina’s many awards and achievements in the manner of WWF presenters. They make a playground of the space. Water gets chucked around – at one point Nina gets a glassful in the face – and then the actors skid backwards and forwards on the wet floor, slamming into the walls (with enough force that a bit of the radiator falls off). They do numerous things that do not look wholly safe. They are purposefully un-careful. A smoke machine is deployed. At one point the double doors get thrown open and a car screeches to a halt outside and a woman in a bright red wig jumps out and screams insults.

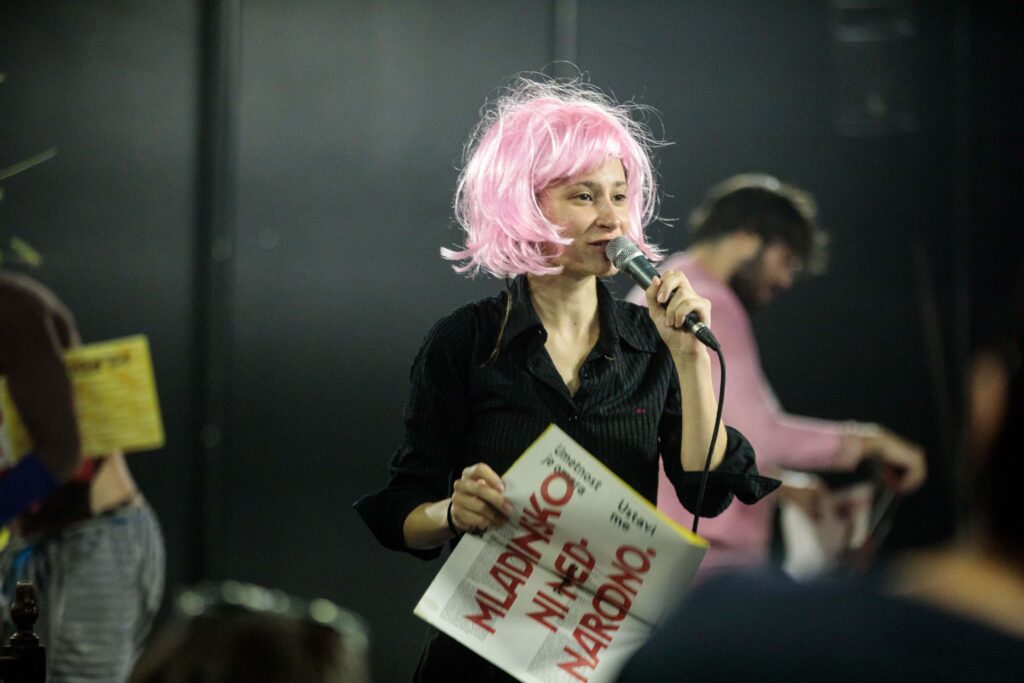

In between all the commotion there are quieter moments, breathing spaces (though there is usually something happening in the background). Nina tells stories about visiting her grandmother in Sremski Mitrovica when she was little; she describes getting high and maybe, possibly shitting herself near the famous German director Peter Stein. She sings (very well). She dons a pink wig. She recites a mashup of the poetry of Milena Markovic. They also quote the late Serbian director Igor Vuk Torbica: theatre is meant to be dangerous, it should problematise.

All the performers give themselves fully to the show, but Marko Mandić is particularly vigorous. He charges around like a bull, launches himself at the walls with daunting force, dons a plastic cape, a skirt of newspaper, a pair of roller skates. Or strips off for ‘naked time.’ But he too has moment to pause and talk about his youth as a young pioneer in Yugoslavia, swearing an oath to spread brotherhood and unity, and to pass comment on the gap between the ‘91 generation and those with lived experience of Yugoslavia.

Nataša Keser and Benjamin Krnetić complete the quartet, the latter wearing a ladies’ formal pink suit, dripping wet, for most of the show. Together they share the weight of the piece, carrying each other. It is a show that is at once gloriously self-involved and a true collective effort. A simultaneous translator is on hand for when they go off script, which is all the time, and his voice and presence becomes enfolded into the piece.

If this has been the whole show, this act of self-study, this self-reflexive exploration of millennial dilemmas and the trap of careerism, this messy essay on theatre and its purpose, a show that explodes the idea of director as a lone operator, it would have been an intense and memorable two and half hours

But it did not end there.

Around two and a half hours in, just as it’s starting to start to feel little wearying, the doors are flung open once more and we are ushered out into the night. Outside there are fires burning in oil drums, flames flickering against the night sky, illuminating a structure of shipping containers. A table is hastily erected and we are all invited to sit around it, to eat and drink. There is hot sausage and crimson, glistening roasted peppers and potato pie, pita sa krompirom. Plastic cups are distributed; there is beer and wine. There is live music. A quintessential Balkan scene. All that’s missing is a pig on a spit.

As the tone of the show shifts, so does the language from Slovenian to Serbo-Croatian (it feels most appropriate to call it that), in a gesture towards the actors’ mixed heritage. We sit there with our drinks around the table, as if at a wake, as they recount a story about a man they call Teča (which means ‘your mother’s brother-in-law,’ the words for family members in Serbo-Croat are very specific). The piece becomes intensely sensory: the sweet smell of peppers, the music of fiddle and accordion, the crackle of flames, warding off the cold with wine. When it becomes too cold – it is April, but it snowed the day before – we retreat to the barrels, warming our hands over the flames.

Nina reflects on the theme of exits and death, on theatre, of last acts and final bows. As the shipping container is crowned by a golden curtain – and then, in a moment of great beauty, it becomes a ship, a great sail is unfurled, billowing out into the sky. It’s just the most glorious thing,

Nina Rajić Kranjac’s Solo

Eventually, Nina, good to her word, vanishes. But this is not the end either. She remerges, talking once more about time, speaking from the past to the present.

It’s hard to articulate the overall impact of the piece, it is a journey, a durational exercise for both performers and audience (past productions of the show talk of a six hour running time and I would have been up for that) a true communal experience, literally feeding its audience. It is intensely theatrical and incredibly exciting. Just really fucking exciting. Theatre as a living art form and a team sport, as an act of trust and risk, breathe and sweat, vulnerability and exposure, chaos and catharsis.

Credits:

Idea, concept and performance: Nina Rajić Kranjac, Nataša Keser, Benjamin Krnetić, Marko Mandić

Set design: Urša Vidic

Composer: Branko Rožman

Costume design: Marina Sremac

Musicians: Petra Božič, Branko Rožman

Lighting design: Matjaž Brišar

Sound design: Marijan Sajovic

Set technitians: Boris Prevec, Tadej Čaušević

Stage manager: Dafne Jemeršič

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0