As theatres in Serbia stage a tribute to Igor Vuk Torbica, Andrej Čanji looks back at the life, work and art of the talented young director.

Performances do not usually have a long life. The good ones might survive in the repertoire for several years, but only the exceptional ones, if they are lucky, can last a decade or two. That is why it is surprising that the first professional production of Igor Vuk Torbica, Moliere’s Don Juan (2013), is stayed in the repertoire of the National Theater “Toša Jovanović” in Zrenjanin for nine years. Many more of Torbica’s productions remain with us.

This month the Serbian National Theater is presenting a revue of five plays by the director, in which the National Theater in Belgrade will also participate. Audiences from Novi Sad and Belgrade will have the opportunity to see the theatrical achievements of the director has not been with us for almost two years now. It is rare for a theatrical production to outlive its director, rarer still that the ephemeral stage opus continues to receive applause from enthusiastic audiences almost two years after the artist’s departure.

In addition to Don Juan, the revue will present his productions of Tolstoy’s The Power of Darkness (National Theater in Belgrade, 2017), Lorca’s Blood Wedding (Serbian National Theater in Novi Sad, 2018), Moliere’s Tartuffe (2019, the National Theater Sombor, 2019) and Euripides’ Bakhe (Bitola National Theater, 2019).

It’s a just a shame we won’t be able to see more of his shows. Some are no longer in repertoires, but theater connoisseurs still remember his earliest work. Even those who have not had the opportunity to watch Torbica’s production of Nusic’s The Deceased (2012), remember the fact that the Yugoslav Drama Theater included in its regular repertoire this exam performance, made during the third year of his studies. As a result, the student Torbica becomes a topic of conversation for the theater-going public. A director from whom much was expected. A promising talent.

He exceeded all these expectations and fulfilled all these promises. Not only for Serbian audiences, but also for Macedonian, Montenegrian, Croatian and Slovenian ones too, wherever he had the opportunity to work. Let me use a cliché, not because I don’t know what else to say, but because it’s true: the audience really loved him, the critics truly appreciated him, his colleagues sincerely respected him. Of course, there are those who did not understand him. They, however, remain in the minority. He was a smart, scrupulous and uncompromising artist who was also charming, beautiful and approachable.

These kind of organizational tributes to an important director do not not happen often. Why does Torbica deserve it? What made him special? There are two main reasons. He represented the theater of the region with his character and his work. As a public figure, he understood what it means to be responsible in the society which you create and to which you have an obligation to speak conscientiously and bravely. He did this several times. Most memorably, when his play was included in the selection of the Theater at the Crossroads festival. He complained in an open letter that the organizer proudly pointed out the President of the Republic of Serbia, Aleksandar Vučić, was the patron of the festival. Torbica felt ashamed that his name and his work were used to promote an authoritarian politician who is a symbol of the division of society and lack of freedom.

In the same letter, he expressed regret that he does not have the right to withdraw his play from the festival – so he invited the production company to do that, and then canceled the previously agreed contract with the theater that organized the festival. Waiving royalties due to principle is something unknown in Serbian theater. Not because the artists lack principles, but because the conditions are very unfavorable. Torbica was special in this respect. Because of his beliefs, he was willing to sacrifice his own well-being. These actions led him to enjoy great respect both in the professional and the public sphere, but he also suffered the hostility of profiteers and idolaters. After The Power of Darkness, which he directed in Belgrade in 2017, no theater in the capital dared to open its doors to him because of a fear of further conflict.

Igor Vuk Torbica’s stage language can be characterized as an expression of high aesthetics. I assume this means that the socio-political aspect of his work did not directly correlate to everyday political life, in the way that the work of directors such as Oliver Frljić, Andraš Urban or Kokan Mladenović often does.

Torbica’s approach is subtle in that sense, but equally contemporary. We recognize reality in his performances at the level of phenomena. The era is not conveyed through the scenography. Costumes do not mark out the period in which the action takes place, though they can play a role in characterization, as is the case with the fur coats that Don Juan and Nikita from The Power of Darkness ostentatiously wear.

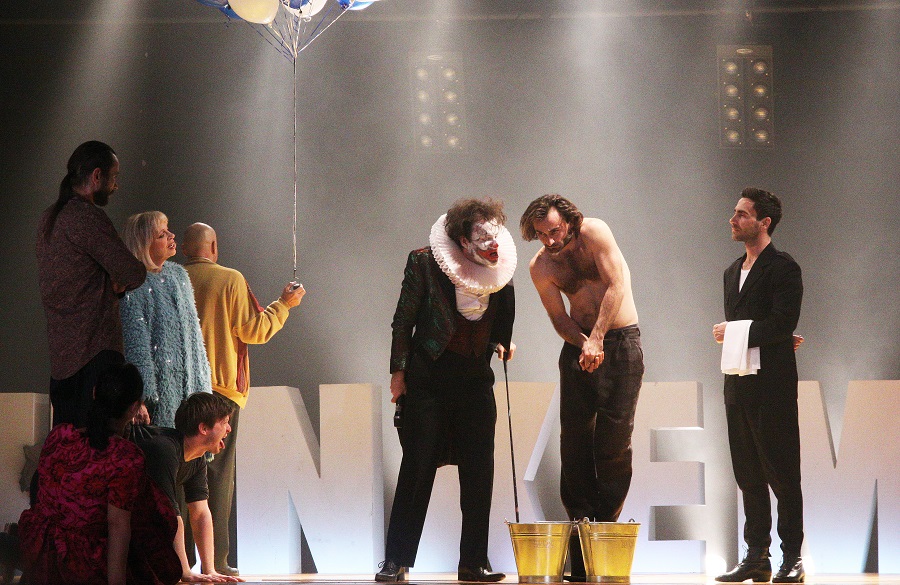

Igor Vuk Torbica’s Hinkemann

Torbica’s Tartuffe symbolizes the modern mechanisms of authoritarian rule. By being polite, contrite and friendly, by behaving like a modern life coach, he gains the favor and affection of typical upper middle-class family. Behind that screen of sweet talk, he intrigues and manipulates until he subdues the whole family and bends them to his will. With a meticulous and minimalist approach, Torbica creates an image of modern Serbian society. It’s not overt. The actors do not imitate regime representatives, there are not even humorous remarks to evoke aspects of Serbian reality. The scenography and costume are used to depict class, but not national symbols. Played in front of a Hungarian, Russian or Turkish audience, Torbica’s production would not point to the authoritarianism of Aleksandar Vučić, but they would recognize Viktor Orban, Vladimir Putin or Recep Tayyip Erdogan as Tartuffe. Torbica’s directing spoke about the concrete through universal means.

His productions form a whole like Balzac’s Human Comedy. Those of us who have watched several of his performances can testify that they are related in style and theme and, as such, they make up a catalogue of human flaws – a textbook that explains our collective misfortune. In that sense, Torbica is our theatrical Dante, attempting to present a comprehensive list of the manifestations of human darkness. In that sense, The Power of Darkness is a syntagm that encompasses the features of his opus. From the early production of The Deceased to the last production Fear – a warm human story (2020), Torbica deals with the evil aspects of the human condition.

In Don Juan he explores why people become followers of a self-confident amoral person who destroys someone else’s life for profit or pleasure. Corruption and nepotism are addressed in The Broken Jug (2015). In Hinkemann, he builds an anti-war grotesque about a humiliated, disabled individual suffering from war trauma who has been left to fend for himself while being hungry and poor. In Titus Andronicus, he criticizes modern colonialism, the responsibility of Western countries for destabilization of Middle East and the rise of fundamentalist terrorism.

In many of Torbica’s performance, the title of the play was highlighted in large luminous letters. Each of his plays seems to be a theatrical study of moral weaknesses, a recording of the character flaws such as Theophrastus conducts in philosophy. This is not the only device that Torbica frequently uses in his work. He often uses lighting as an important means of communication. In Tartuffe, the characters emerge from the depths of the stage darkness in front of the audience, and when they leave the stage, they return to the darkness. Even the lighting in the auditorium becomes an important aspect of his poetics. In Tartuffe, the show begins with the lights in the auditorium completely on. As the action progresses, the lights slowly fade out. In Hinkemann, the actors occasionally address the audience with the lights turned on in the auditorium. It’s a directorial attempt to connect the events on the stage directly with the audience. The sense of illusion is often annulled by playing with the lights in this way. An audience protected by its passive role must be shaken out of its comfort. People must be reminded of their own responsibility.

Torbica didn’t direct contemporary drama. He entered instead into a dialogue with works from the past by changing and adapting them for a contemporary context. All of his productions are authorial projects based on the motifs of classical plays. In Don Juan, he transforms the famous scene with a beggar. In the play, he asks for charity and promises to pray for the person who gives it to him. The protagonist scoffs at this; if a beggar prays constantly and he remains poor, it is as if God does not take care of him. Don Juan instead promises the beggar a coin if he will curse at God. The beggar refuses and Don Juan still gives him a coin.

In Torbica’s production, after contact with Don Juan, all the characters become his followers. His insatiable longing and obsessive need to deprive the people he comes into contact with of all their beliefs in order to become an object of worship is brought into question in the scene with the beggar.

As directed by Torbica, the beggar is not looking for a coin but a cigar. He has no essential needs or ambitions in life. He is a calm, modest and satisfied man. A person who does not have a single desire, and thus no space for Don Juan to disturb his peace with his diabolical provocations. In the meeting with the beggar, he questions himself, his actions and wants to follow the beggar. In this moment, even Don Juan’s most ardent followers might suspect that the person they thought of as an omniscient leader, a man capable of refuting every argument and destroying every value, does not hold the answers.

In The Trickster of Seville and the Stone Guest by Thirso de Molina, Don Juan and his loyal servant are punished and sent to hell by a transcendent force. Moliere spared the servant. But, with Torbica, there is no transcendence. Don Juan and Sganarelle not only do not suffer, but their company of followers expands, a band of new Don Juans who will seduce gullible people with their deceptions, charm and charisma.

In his earlier productions, Torbica’s aesthetics were always wholly legible. It is not clear what Don Juan represents. Is the title character a representative of insatiable capitalist consumerism or a symbol of seductive populist politicians, or is it a universal story of seduction and longing?

Throughout Torbica’s oeuvre, we see constant variation on the theme of human failings. The difference between his adaptation of Moliere’s Don Juan and his Tartuffe, six years later, is one of a more mature, precise and defined expression of these themes. His production for the National Theater in Sombor, began as an improvisation with the actors on current topics. It is only through this improvisational work that the ensemble realized the project was moving in the direction of a plot that corresponds to Moliere’s comedy.

Igor Vuk Torbica’s Tartuffe. Photo: Sinia Trifunovic_

Antiquity offered a solution to the plot via the deus ex machina in which a deity solves the problem. With Moliere, the solution was rex ex machina, the arrival of the king’s envoy who conveys the king’s will. Torbica’s production presents the provocation of whether we can count on a solution based on the model of democratia ex machina. He achieves this at the very end of the performance with a picture of the defeated Orgon family. They sit at the family table, talking and eating while the lifeless body of their murdered cousin lies under the table. Tartuffe, as an envoy of totalitarian will, killed the only person who did not succumb to his blackmail. All the others are accomplices and hostages of the regime. During the meal they look under the table, and, after that, the performance ends with them looking at the audience. No transcendent force comes to the rescue and the wicked are not punished. No mercy of an absolutist monarch will stop this repression. This is a break with the traditional solutions to plots that depend on higher powers, a reflection of the democratic, secular age that requires an enlightened, engaged and strong society willing to fight for its own rights. Similar calls for responsibility are the leitmotif of Torbica’s work.

Politics was the ultimate goal of Torbica’s art, but the means he uses to achieve his intentions are what also sets him apart as an original phenomenon in the region’s theaters. The use of shock and brutality are common. In Hinkemann, which critics singled out as a theatrical event of the decade and declared as the director’s tour de force, there is a scene in which the actors play American football with a bloody human heart. In Titus Andronicus, Aaron begs the audience to take and save his two-year-old new-born shown in the form of a bloody liver. In The Power of Darkness, where the audience and the stage are separated by a transparent wall, Nikita holds a realistic new-born doll by the leg and slams it against the barrier while blood splashes and organs fly in all directions.

Humour was also a constant force in Torbica’s work. It is achieved in various ways, through choreography, sudden jokes, or self-referential moments. In his work, every detail has its function.

His work was not without its weaknesses. In Don Juan, Torbica did not elaborate on the female characters. The bride is given the task of constantly running after the title character, a man. In Tartuffe, he introduces the character of a handyman, who often interrupts the dialogue by repairing the set, as a comic relief. Although it is a very funny addition, it is notable that while all the characters who represent the upper middle class are subordinated to the regime, the fate of that ordinary worker remains unclear.

These insufficiently elaborated moments reveal perhaps the crucial feature of Torbica’s directorial approach – a sense of constant experimentation and a search for new solutions and ideas. That sometimes comes with a risk of being vague or ambiguous, but that is rarely the case with Torbica. The imagination on display in his work is always refreshing. Even when he repeats a device, it is not as a result of recycling old material due to lack of new ideas. He repeats the same things as part of his own poetics and always changed the meaning by placing it in a different context.

The director Kokan Mladenović called Torbica “the prince of the theater.” He left us early, preventing his own coronation. He could have been the ruling master of the theater in this region. He dedicated his work to the fight against darkness. His weapon was theater. Because of the way he left us, we learned that all this time he was actually fighting two battles. One with the darkness of society and the other with his own demons. And now we can already guess that like Scheherazade, who was prolonging her life with a stories, like Aska, who kept the voracious wolf at bay with her dance, Torbica kept himself in the battle with the magic of his theatre for as long as he could. He led our theater down unprecedented paths and illuminated our path to goodness.

Andrej Čanji is a theatre critic and theatrologist based in Belgrade.