Yugoslav Drama Theatre, premiere 17th April 2024

In April, Andrej Obradović went on hunger strike for five days. In February, together with his mother and the LGBTQ+ organisation Da se zna, a complaint was made against two police officers for brutalising and sexually humiliating him and a bisexual woman during a search of their home on 16 February following a tip-off for drug possession. However the Novi Beograd police station rejected the allegations against the two officers and the public prosecutor’s office did not respond to the criminal complaint.

The biased gaze of the judiciary has touched many lives in Serbia. Andrej Obradović decided to stake his life on a demand: that the judiciary in Serbia should put an end to protectionism, to a system that protects some but not others. Andrej Obradović’s case is just one in a countless series of similar cases in the country in which the prosecutor is obliged to hide her face from photographers and run away from journalists.

On 17 April, the day Andrej ended his hunger strike after being admitted to the prosecutor’s office and assured that the preliminary investigation will continue, the premiere of Boris Lješević’s production of Michael Kohlhaas by the German playwright Heinrich von Kleist took place at the Yugoslav Drama Theatre. This felt apt, as Michael Kohlhaas is based on a true incident and tells the story of a highly righteous man whose love of justice was so strong and principled that it turned him into a bandit and murderer.

The romantic hero Kohlhaas, an honest and respectable horse trader, seeks justice after a brutal encounter with a local lord. When the legal system denies him fair treatment, he begins a violent rebellion in which the line between victim and villain becomes blurred. Kleist’s story deals with themes such as revenge, justice, the corruption of institutions and the destructive influence of anger. The speciality of Kleist’s narration lies in the fact that it is not so much interested in who is right and who is wrong, but about what is right and what is wrong on a general level. The universal appeal of the story stems from the fact that Kleist fills it with many contradictions that apply equally to the protagonist and the antagonists. The matter becomes so complicated that the reader must ask himself general questions about the possibility of justice ever functioning objectively and fairly and ever being freed from political influence.

There is perhaps no story better suited to the current situation in Serbia than Michael Koolhaas, because it deals with justice denied. At the same time, however, there is perhaps no more problematic story for an artistic confrontation with injustice than Michael Koolhaas, whose plot is triggered by numerous situations that arise by chance and in which the responsibility of all the characters is relativised in various ways. The philosophical potential of Kleist’s masterpiece thus collides directly with the need of Serbian society to experience a catharsis in the injustice it experiences on a daily basis.

The dramaturg who takes on the task of dramatizing this story and the director who takes on the task of staging it are therefore faced with a choice: do they want to explore the fundamental tension between law and justice on the level of an abstract phenomenon or do they want to translate the story into a contemporary context and enter into the political struggle with a real corrupt judiciary and political regime through concretisation.

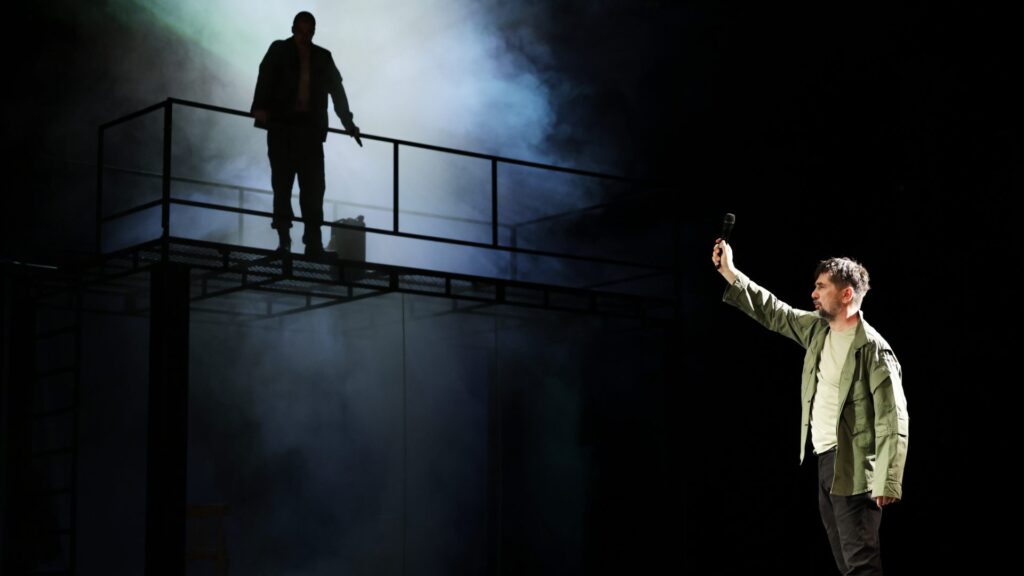

MIhael Kolhas. Photo:Nebojsa Babic

Playwright Fedor Šili and director Boris Lješević have worked together many times to adapt classics for the stage. However, despite their considerable experience, the results in this instance are inconsistent, as Lješević himself admitted in an interview he gave to the newspaper Danas: “Sometimes in these decisions lies the lack of a real idea, so I leave it to the great classics and the great writer to speak instead of me. Sometimes I have nothing to say, then I find my reasons spontaneously, during rehearsals. But sometimes I do not find them at all. And you can feel that in the performance.”

The lack of an idea was noticeable in his production of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the process of which began around the same time as the war in Ukraine. A great novel became a simple melodrama which had nothing to do with a tectonic historical moment. I could not see any significant difference in his production of Michael Koolhaas. There was a distinct lack of attitude in its narrative passages. Speeches were delivered by actors to the audience at seemingly randomly selected points. The scenography was minimal. All of which are established aspects of Lješević’s directorial approach.

At the same time this production, skilfully uses the alternation of narrative style and dramatic expression that Šili and Lješević have perfected over time. For example, Vojin Ćetković, in the role of Koolhaas, often retells certain parts of the story, only to soon switch to a dialogue in the here and now with the other characters. When the characters talk about past events, the position from which they speak is in no way defined. On the contrary, when they narrate in the perfect tense from the perspective of a future version of themselves, the characters act as if they are experiencing it now. There is no distinction between the two ways of conveying events, showing and telling.

The beginning and ending of the production is also typical of the way in which Šili and Lješević transfer prose to the stage. At the beginning, the ensemble spontaneously gathers on stage, the actors prepare for the performance and cheer each other on with a quote from Hamlet: “To be ready is everything.” Such an informal, relaxed introduction is matched with a completely anticlimactic ending, in which the actors exchange somewhat confused glances after Koolhaas’ execution and repeat several times, shyly and questioningly, that this is, indeed, the end.

Although this was in some ways a skilful dramatization of this romantic tale of injustice, the director’s reluctance to bring real-life motifs into the play to draw a parallel with the politicised justice and compromised institutions we encounter on a daily basis is evident. Instead of showing the concrete face of evil that he supposedly wants to talk about, Lješević hides it behind abstract figures.

Vojin Ćetković is very lukewarm in the title role, mainly because his interpretation does not recognise the major changes that the main character undergoes. We do not get a real sense of the principled, systematic man who turns from righteousness to vigilantism. Junker Wenzel von Tronka, played by Aleksej Bjelogrlić, is undoubtedly an unprincipled but not actively evil nobleman. Rather, he is a kind of egotistical weakling, a worthless villain who has no will of his own because he lets his subordinates do as they please.

In the service of his characterisation, the most striking scenographic object was created – a large, moving, transparent room with a home cinema on which von Tronka plays video games, a departure from the prevailing scheme of acting in an empty room. Lješević feels the need to create a direct parallel to real-life circumstances. However, considering that only video games are recognised as a necessary reference to the modern context, one gets the impression that there is a fear of introducing more dangerous and far more relevant motifs of violence that dominate Serbian society into the production. This impression is reinforced by the fact that research clearly shows that video games do not contribute to the increase of violence in society and that this is a myth that even the Serbian authorities like to use as an excuse and justification for their own involvement in exacerbating tensions in society.

MIhael Kolhas. Photo:Nebojsa Babic

Zoran Cvijanović and Voja Brajović’s portrayal of the Electors of Saxony and Brandenburg are also problematic because they are portrayed humorously. Cvijanović plays a frightened and confused ruler who is credited with using opportunities to provoke laughs, while Voja Brajović is completely at ease in the informal organisation of the play, clowning around every time he appears on stage, refusing to use the microphone and on other similar occasions. The further the play progresses, the more frequent the humorous gestures become, which makes a potentially poignant and multi-layered story feel increasingly frivolous and detached from reality.

Šili and Lješević are the undisputed masters of telling classic literary stories. Their complete understanding of the technique of plot management is undeniable. What makes them weak in my value system is their refusal to go one step further and animate their formally dynamic fictional universe with factual references.

Turning away from an attitude towards history is, in itself, an attitude. It is undoubtedly a legitimate position. The only question is from which value system we approach the theatre. Is it for us the perpetuation of an atmosphere in which there is no responsibility for the evil we live in, so that we are all equally responsible, as suggested by the song by King of Čačak, who created the music for the show, recited in the play with the words “Save us from ourselves”, or should Andrej Obradović, that is, what his case represents, clearly be part of a free and courageous art. Due to such a polarised idea of theatre, I left Michael Koolhaas” frustrated. Instead of a catharsis, I experienced a piece of theatre that felt disingenuous and disinterested despite its artistry.

Credits

Andrej Čanji is a theatre critic and theatrologist based in Belgrade.