Žiga Divjak is one of Slovenia’s most in-demand young directors, his work frequently exploring social injustice and environmental issues. He talks to Natasha Tripney about why we need to change our thinking about climate change.

Natasha Tripney: You have two pieces at currently at Mladinsko Theatre, The Game and Fever, which could be described as documentary theatre. What is it about the form you find exciting?

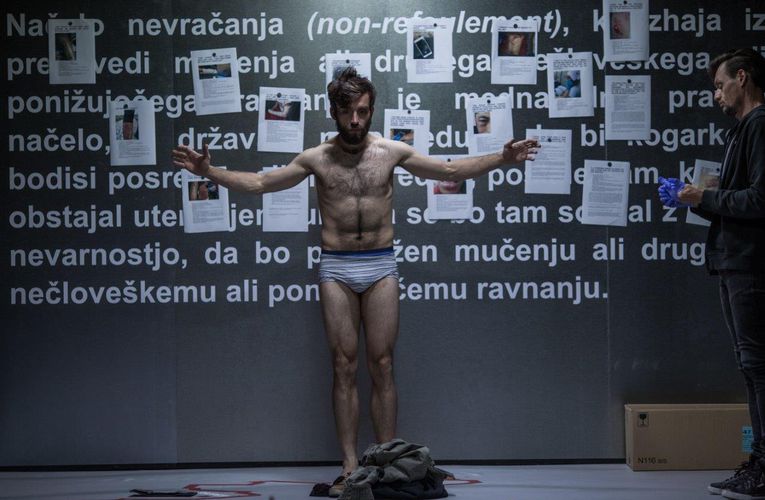

Žiga Divjak: The pieces are quite different. The Game is based on the testimonies of the people who tried to cross Croatia, from Bosnia, to enter the Schengen zone. We found their testimonies on the Border Violence Monitoring Network. We try to provide some context, so the audience understands what is actually happening beyond the testimonies. Fever is based on facts, but it’s more about the general state of the world. And what can be done, how do we deal with this [climate] crisis.

With Fever, I read a lot of articles, a lot of books including Andreas Malm’s book, How to Blow Up a Pipeline as a new perspective on how the environmental fight should become more radical. I’m not like a big fan of violence, but it makes you wonder what’s the what’s the appropriate response right now and what will produce some sort of a change in society?

I wanted it to be a mixture of images and scenes without words, to catch the atmosphere of the dying world, to be post-apocalyptic, but not too much. I did not want to go deep into this post-apocalyptic aesthetic, I just wanted to glimpse a bit of it. A lot of things were actually created by the improvisation and homework of the actors and I tried to devise it into a coherent whole.

Natasha Tripney: There’s a strong musical element to Fever; at times the actors’ voices sound like a chorus, at other times like the chants of protesters.

Žiga Divjak: I played with this [technique] before in some other performances, but here I went really into it. It happened in one rehearsal that one of the actors made a scene in this way. Though it was completely different from this finished performance, it really made me think that this was the right form. This score is very interesting for me because we are all in it together. It’s like a machine. It’s like a frustration which is expressed only through words and through screams. The idea was not to create pleasant music, but something a little annoying, polysonic, operatic.

Natasha Tripney: You have also directed Duncan Macmillan’s play Lungs. Can you tell me a bit about your concept for the production?

Žiga Divjak The public is divided into two. They see each other. The actors also look at each other. They’re sitting on chairs with microphones. And in between them is a living room table with a computer, a cell phone, a book, everything a creative person would have in their living room. And there’s a block of ice, which is slowly melting. And because it’s melting, it’s destroying the computer, destroying the cell phone, destroying the book. So during this hour and half, the ice melts. It’s scary because you [instinctively] react when you see something dropping on your iPhone.

The two of them are discussing whether to have kids or not to have kids. When I read [the play], I thought it’s very well written, but that it’s a first world problem. So, I really wanted to make it like, while we are talking about [climate change], it’s already in our living rooms. While we are discussing what to do next, it’s already here. It’s already, in some sense, too late. It’s a reminder that some concrete action should happen.

We are all filled with this feeling of guilt and trying to find a solution, but these solutions, they are important, but they’re still consumer choices, which is not really a solution. It’s great that we try to avoid plastics. It’s great if we try to avoid eating animal products, but it’s not enough.

Natasha Tripney: What is like to be both a young person and an artist living in Slovenia at the moment, given the current political climate?

Žiga Divjak: In short, it’s a terrible situation, because we are kidnapped by this psycho figure of our prime minister [Janez Janša]. For the last 20 years, all the politics has been [centred around] him. Either he wins, or somebody wins because he’s in opposition to him, which is also a problem. Most of the time, we are not voting for something, but we are actually voting against a person, which is insane. And that’s why we are stuck in this moment. This is not to say that everyone is the same. We do have some small parties, which now look like they might be some sort of an alternative. But [the government] has damaged society. We are deeply divided. They have destroyed a lot of media, changed a lot of public institutions. It’s really a bizarre thing, because I’ve never met a person for quite some time who would agree with them. But, somehow, they just stay in power.

Žiga Divjak’s Fever at Mladinsko Theatre

Natasha Tripney: There have been a lot of cuts in arts funding?

Žiga Divjak: The independent scene has been shrunk, by a lot. Their approach is, basically, anything but progressive. It’s like: we have to take care of our old buildings, we have to take care of classical stuff. Of course, they didn’t really manage to do this, because the art scene is really opposed to them. We’re still struggling – but the atmosphere is bad. I hope they will be defeated in the elections, but I think the damage is already done.

You have a sense that we are now dealing with things of a past, not the future, which is most problematic for me, because they’re coming up with the Second World War issues and stuff like that. It’s so bizarre and it’s so stupid, you want to say: come on, people, we have problems now, can we stop dealing with the past?

Natasha Tripney: The Game was made two years ago, but with a new wave of migrants coming from Ukraine – and with many countries waiving visas and doing all they can to help – it takes on a new resonance.

Žiga Divjak: I’m shocked at how openly racist things have been. Literally the government of Slovenia said that the people fleeing Ukraine are culturally different than people fleeing in Afghanistan. Of course, this is present all the time. But it used to be denied or hidden. Now it’s just plain. It’s trying to divide people who are all fleeing war, which means potentially they could be comrades in a common fight, to change the society in a way that such a situation wouldn’t be possible. Because, again, this war in Ukraine is, from my perspective, a thing of a past not of the future and at a moment when we really should all unite to fight against climate change and to find a way to survive us as human beings, as humanity.

Natasha Tripney: What was the situation like for theatre artists in Slovenia during the last two years of the pandemic? How much support was there?

Žiga Divjak: It was a hard time. The government provided some funding, sort of a basic income. Without that it would have been a disaster. But the problem came when the funding stopped, and a lot of people from the independent scene didn’t have any open projects. It was really hard to make a living. I have been fortunate, as a director. The problem was for the actors who did not work. They were engaged, but not in the post-production, which is where most of the money comes from. So that was problematic. In the theatres, we created stuff, but we didn’t know when it would be presented. Schools were closed, kindergartens were closed, but we were still working. And, while I believe theatre is really important, it’s not as important as school.

Žiga Divjak’s The Game at Mladinsko Theatre

Natasha Tripney: How do you square environmental concerns with working in an artform that requires movement of resources and people? Could institutions be doing more to address the environmental impact of touring?

Žiga Divjak: I believe that it’s important what we do in our everyday life, but I think like that art is trying to broaden the mind. So to say now we will be closed in our small societies and try not to move is a bad way of dealing with this problem. The super-rich people have their own private jets and super yachts, which produce a crazy amount of unnecessary emissions. I really don’t want, as an artist, to be taking too much pressure on ourselves, because I think art is on the frontlines of producing a new value system.

When I was discussing my work with students, some of them thought that these performances were made to try and create a guilt trip. But it’s really not my intention. I want us to feel angry, not guilty. And of course, that does not mean that it’s not our responsibility to do the work. In the broadest way, we are all guilty, but our choices are rather limited in a lot of aspects of our lives. I’m interested in what we consider to be violent and what is not violent. I really hope that the time will come when we will perceive somebody driving a luxurious car as a crime. Not just: oh, I have a money, I can afford it. It doesn’t matter if you can afford it, because the environment cannot afford it. You are actively killing future generations, and already killing people living in areas that are that are environmentally more exposed to climate change.

People who are in a precarious situation, struggling with how to get from month to month, buy produce at cheaper prices, but at what expense? At the expense of the environment and at some other worker being exploited. This is an endless circle, which we are trapped in and we are all guilty of it. I don’t want to change my phone every couple of years, but it breaks. It just doesn’t work. In-built obsolescence is a crime against humanity. We have the capacity to create something that would last for a century, but we don’t – because of this idea of endless growth, which is completely insane. And we are still stuck in it. Now we have an election and everybody’s talking about GDP growth. This is insane. This is the wrong thing to focus on.

Natasha Tripney: In Serbia, protestors had some success standing up to mining corporation Rio Tinto, but this kind of environmental damage is more easy to visualise, whereas I guess climate change is more abstract.

Žiga Divjak: That’s the problem. It’s so abstract. And even when you read everything about it, and you’re very well aware, on some level, you still believe it’s not true. I don’t mean you’re a climate denier. But it’s so hard to comprehend. It’s so hard to make sense out of it; it’s just impossible to imagine that it’s going to be that bad – you still hope that some magic will happen, or something will happen. I’m not trying to defend fatalism, it’s really useless in that regard, but to be too optimistic is also problematic or to bet that technology will save us.

Natasha Tripney: Do you think the Degrowth movement is a better way forward?

Žiga Divjak: I think that, for now, it’s the only thing that makes sense. And that’s why I think that art is so important because we really need to completely change our value system from believing that nature is divided from humans and that it’s something that should be conquered, or something that we possess. It’s a completely wrong ideology. It will drive us to the end of world or, definitely, to the end of humanity. We need to understand that it goes both ways all the time. And there’s so much we could learn from nature of which we are part, from which we are not divided.

Further reading: Ecocide is Everywhere in Serbia, but Eco Theatre Remains on the Margins

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0