Playwright Doruntina Basha talks with Gresa Hasa about her new play Stiffler, the prevalence of femicide in the Balkans and wider society, and the role that art can play in the feminist cause.

Doruntina Basha is an award-winning playwright and screenwriter from Kosovo. Her work includes‚Gishti, which won Best Balkan Contemporary Play at the MESS International Theater Festival Sarajevo, and the screenplay for Vera Dreams of the Sea. Her new play Stiffler is about Hava Mara, a sex worker who is stabbed in the back and how she is systematically ignored, dismissed and derided as she tries to seek help.

Gresa Hasa: How did “Stiffler” come to life?

Doruntina Basha: Stiffler is a work commissioned by INTEGRA, a non-governmental organization in Kosovo, formed in 2003 and which focuses on human and minority rights. Sometimes they include art in their activities and specific projects. This time they wanted to concentrate on sex work and I was

offered to contribute to the topic.

No matter the initial idea that prompts the writing process, the story and the characters have a life of their own and often they determine the narrative, despite the desires of the playwright. Therefore, Hava Mara took on the identity of a woman in her 40s whose body is criminalized, before any crime has taken place, because of how she makes her living.

I am unable to separate the experience of a woman who is a sex worker from the experience of other women. Stiffler ended up becoming a work that deals with systemic oppression, gender-based violence, and femicide. and not an exclusive project about sex workers who are regularly dehumanized and perceived as being detached from the actual system, in a world that refuses to acknowledge their existence.

I wanted to portray female sex workers as they are: women like the rest of us. Human beings and citizens who are discriminated against and dismissed in an oppressive patriarchal system.

Gresa Hasa: The knife in Hava Mara’s back can be perceived both ways: it is both an actual knife and also a symbolic knife. Does this knife have such a wider meaning?

Doruntina Basha: Stiffler is a sort of elaborated metaphor for the knife that we all bear in our backs. In this play, the main character is a sex worker who has been stabbed by this knife. Nevertheless, this does not mean that other women with different experiences do not bear a symbolic knife in their backs that weighs just as much. Gender-based violence is deeply layered and this is especially notable in the societies in the Balkans. There are women for whom this knife takes the shape of economic insecurity; sexual harassment in the workplace; the burden of unpaid labour within the traditional household; the way how property and heritage are divided and allocated. For others it can be their unconventional gender identity or sexual orientation in a violent heteronormative context.

If we analyse the position of women in our societies, we will find a knife in each of their backs. Moreover, the thrusting of the knife in someone’s back symbolizes a cunning manoeuvre— a historical malevolence and injustice that is done to women.

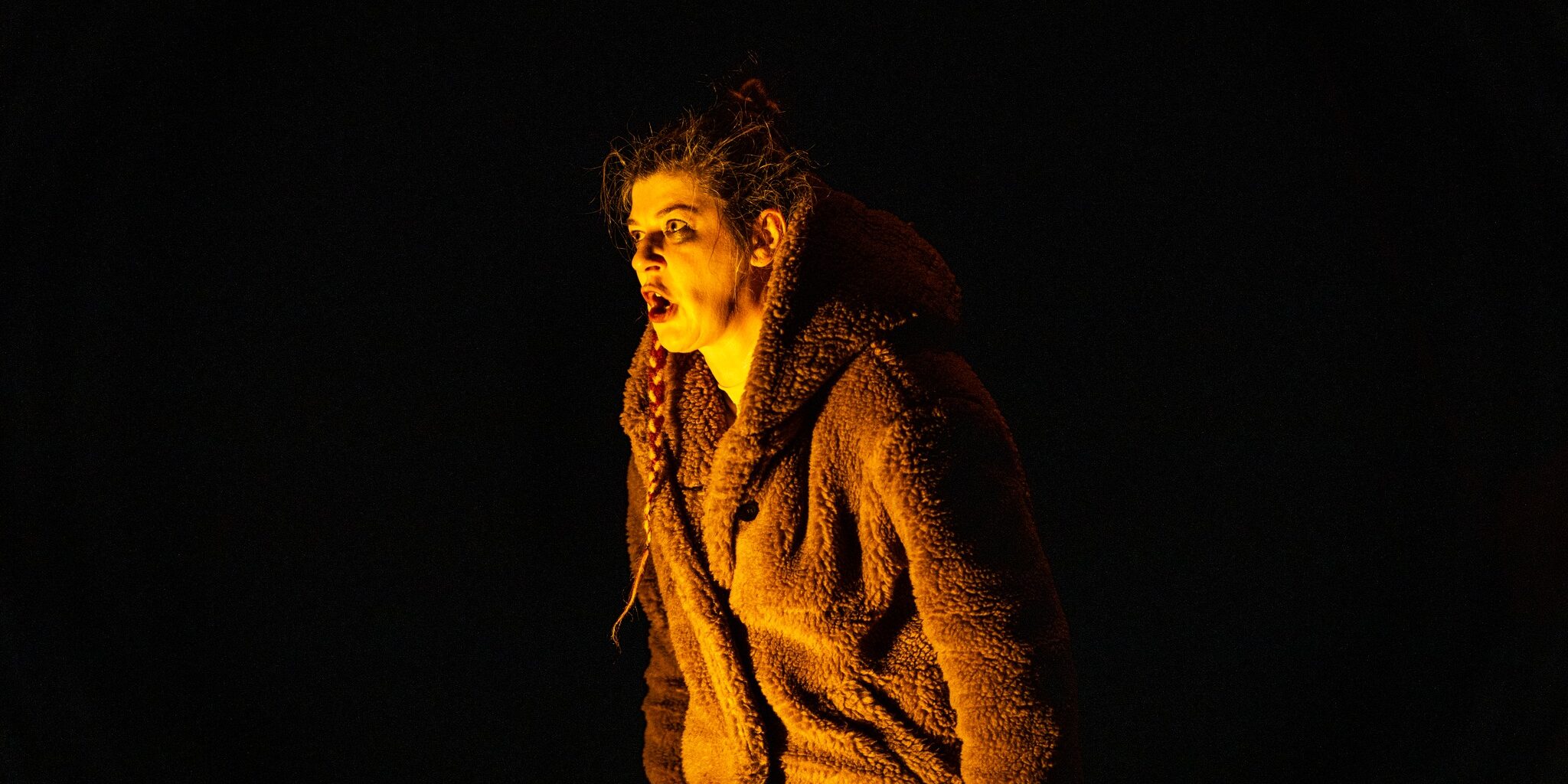

Stiffler at Teatri Oda, Prishtina. Photo: Sovereign Nrecaj

Gresa Hasa: How does this knife cut in the current context through Hava Mara?

Doruntina Basha: Hava Mara’s body is not a body but a crime scene. This is a criminalized body. A crime in itself. I wanted to stratify the violence, discrimination and femicide exactly there, in a body the existence of which is justified beforehand to be violated and murdered because she is putting this body in the use of sex work. By making this body political, giving it a story and changing it from “a crime scene” to a subject to whom injustice is done, I wanted to shift the perspective and bring Hava Mara to the scene as a person, a woman who is asking for help in various institutions but consequently is being dismissed and discriminated against. I believe many women would identify with this institutional negligence and treatment. Here is when an invisible bridge is created which connects the audience to Hava Mara and thus brings empathy and a better understanding for the reality and experiences of the other.

Gresa Hasa: The German playwright Bertolt Brecht advocated for a theatre that overcomes spectacle. It is a dynamic event with a transformative potential. It does not only engage with the masses but it struggles towards change by developing collective critical reflections. Theatre is not stripped of responsibility; on the contrary, it claims responsibility. In his seminal essay A Short Organum for the Theatre” he writes: “We need a type of theatre which not only releases the feelings, insights and impulses possible within the particular historical field of human relations in which the action takes place, but employs and encourages those thoughts and feelings which help transform the field itself.” How does Stiffler contribute to Brecht’s concept of an “active theatre”?

Doruntina Basha: First of all, there is femicide in Kosovo and the rest of the Balkans and femicide is normalized. We live in the digital era. The interaction with others, stories, news and events happens through digital platforms. These platforms regularly manage our reactions but they leave us in a passive state. In this interaction we are spectators. In the current system the discourse on the

murdering of women comes of in such a way that it only contributes to the spectacle. It does not

address the phenomenon with the aim to inform about it or understand it correctly and thus provide solutions. It only aims for sensation, a dark show and impotent shock. Theatre is also a medium but a physical medium—a scene where the interaction is separated from action.

Stiffler is a piece of life. It starts with a request for help and ends with a dismissal to this request which has fatal consequences because Hava Mara dies in the end. People sit in the comfortable chairs, witnessing the piece of life that is brought to them directly. They do not read about it. They do not hear about it. They witness it as it unfolds in front of their eyes. By imitating the passivity of everyday life, theatre opens some windows through which the abuse is seen in a very explicit way.

The public does not only see the consequence of this abuse as it happens through digital platforms. It also sees the administration of the abuse. And this causes strong emotions and at the same time shifts the reality for the spectators by making them reflect critically on what they are watching. The spectator continues to be passive but a transformation has already occurred inside of them because now they have also become witnesses.

Gresa Hasa: Hava Mara starts out as a survivor of attempted murder and end as a victim. How does Stiffler differentiate itself from other stories of femicide?

Doruntina Basha: This is the story of a woman who dies. It is not the story of a woman who survives. There are very few women who survive. Moreover, Hava Mara is the justified motive of death. The integrated motive in her being makes one believe that Hava Mara is dead the entire time. The audience has been a loyal companion to her over one and a half hour of a torture that is regulated via legal mechanisms against a woman who is treated not as a victim of a crime but as a criminal herself – until she is left to die. I wanted to be faithful to the reality of women who have been victims of femicide and to the experiences of the public even though I personally desired the opposite: I wanted Hava Mara to live, but at the same time, this is an imposed desire, not a reality.

The medium contributes as a tool that transforms the classical narrative of what happens to

the women that are victims of abuse. These women are even disrespected post mortem. They are never treated with dignity, empathy and justice. Actually, they are blamed for what happened to them.

In Hava’s case: she is a sex worker. If you place a sex worker in front of the public, there is a high chance that many of these people will not sympathize with this woman because there exists an unspoken conviction, a sort of social consensus, that sex workers deserve what happens to them. By witnessing Hava’s struggle and maintaining the distance from her, the same people in the public might imagine for a brief moment being in Hava’s position. We are spectators in our every day routine. What is our role as spectators? My hope was that a story like Hava’s will make the public reflect on the everyday life where news of femicide is “sold” with the same eagerness as showbiz.

Gresa Hasa: In the last scene, Hava is dead and two attendants in the morgue, two men, are speaking of her, trying to determine who she was in the society she left behind. They seem unable to choose between the derogatory terms “whore” and “prostitute”. The discourse is one of the most political elements in the play. The focus shifts from the characters to the space itself and who determines the narrative in this space. How would you comment on this?

Doruntina Basha: This is an interesting remark. The attendants have the space to be listened to but Hava is not granted the same space. Throughout the play, her struggle to speak, to denounce the crime that was done to her, is met with bullishness, dismissal and harassment. She is regularly interrupted.

Who decides which stories matter? Who decides who belongs and who matters in the public space and who does not? This is the absurdity of a battleground where the ones in powerful positions determine the stories that matter. Stiffler shows how the story of a woman with a knife in her back does not matter.

Gresa Hasa: The script is written entirely in Gheg Albanian and often in the slang of Prishtina. What was the purpose of making Hava Mara and the other characters speak in this specific way?

Doruntina Basha: This is the first time I write in Gheg Albanian. Previously, all my other works have been in standard Albanian. In Stiffler I decided to write in Gheg for two reasons. Firstly, I wanted to break the cultural barrier. For us in Kosovo standard Albanian is a barrier. It does not come naturally and lacks a wider range and vocabulary for us to fully express who we are. At the same time, I did not want to alienate the public from Hava Mara or the other characters.

It made no sense for Hava Mara to speak the standard language. I wanted her to be one of us. I wanted the audience to feel close to her. Secondly, the cultural scene in Kosovo is very rigid. The perception of theatre is that it is elitist. I believe that the Kosovar theatre scene must be further democratized. Someone like Hava Mara deserves to be there.

This was also an attempt to reclaim this space and make it possible to speak Gheg and slang on stage. On the other hand, the inclusion of the Prishtina slang was to bring to attention a highly toxic rhetoric that is well-established and institutionalized. I wanted this to be manifested where the victim of femicide is lying, unheard, un-helped, and finally dead, in the middle of the stage between two men.

For example, the meaning behind the expression “O bir!” (“Son”), one of the most common expressions between boys and men in Prishtina, that the attendants use when they refer to each other, has a simple translation. “O bir” (“Son”) means “Biri im” (“My son”) which in itself it means that “I have f*cked your mother, thus you are my son, thus you are under me.”

Gresa Hasa: Your previous works have had regional and international recognition. Gishti (“The Finger”) was shown in Italy, Vienna and the US, Will Stiffler go through the same journey?

Doruntina Basha: I think so. In May this year, the play will be shown in Belgrade, as part of the Mirëdita, dobar dan festival. There is also a plan to bring “Stiffler” to Albania and North Macedonia.

Stiffler is at Miredita Dobar Dan Festival on 26th May 2022

Further reading: SEEstage’s review of Stiffler

Finding Their Voice – making feminist theatre in Albania

Gresa Hasa is co-founder and chief editor of the feminist magazine Shota. She publishes regularly in national and regional media concerning issues of politics, culture and feminism. She studied Political Science at the University of Tirana and for many years has been involved in grassroots organizing in Albania, initially with the student movement and currently with the Feminist Collective, a progressive movement which demands social justice and gender equality."