Teatri Oda, Prishtina, premiered on 4th December 2021

Hava Mara, a sex worker, has been stabbed in the back. She has been stabbed by one of her nameless regular clients.

Written by the playwright Doruntina Basha, Stiffler tells how Hava, a woman of 40, seeks treatment for her injury and is neglected, rejected and, finally, stifled by a patriarchal system that is more concerned with the morality of victims than punishing their abusers.

In pain, Hava is obliged to go to the Emergency Room, where she has to deal with two nurses who are alike in every way, they think alike, lack humanity alike, they even speak as one. These nurses are more concerned with their bureaucratic procedures than with helping Hava; they shower her with personal questions: how come she was stabbed in a motel? What was she doing there? With whom was she doing it?

They don’t listen to Hava’s pleas for water, nor do they remove the knife from her back. The pink wigs and the exaggerated facial expressions of these nurses make them look like cartoons, their appearance, along with the dialogue and their utter unwillingness to assist a bleeding woman adds to this heightened feeling. Director Kushtrim Koliqi uses the absurdity of the scene to strike at the audience.

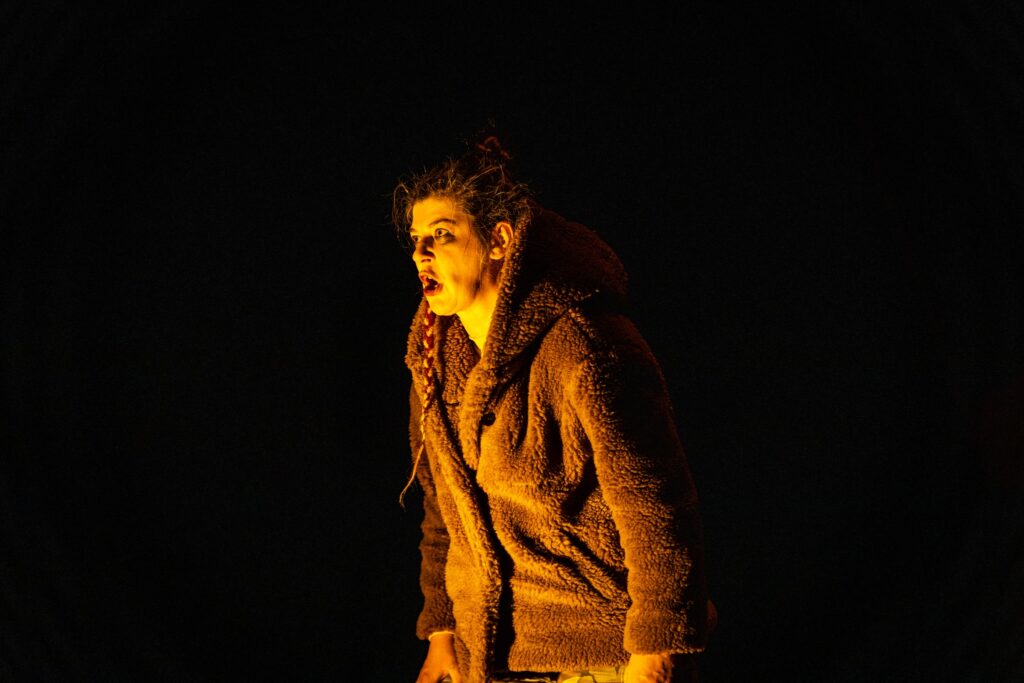

Rebeka Qena in Stiffler at Teatri Oda, Prishtina. Photo: Sovereign Nrecaj

Rebeka Qena, as Hava, does a tremendous job. Through her poise and delivery she conveys a person who is in great physical pain but whose soul also aches from the way in which she is mistreated and rejected by society. Alongside her, Adrian Morina and Armend Smajli impressively play multiple roles: two nurses, two cops, Hava’s brothers and the morgue workers.

When the hospital closes its door on Hava, she goes to the police station. There she finds another brutal system, with a set of people who would rather dig her grave than help her. It’s a system that vindicates men and sees women merely as seekers of their own deaths, it puts the blame on them and their behaviour for aggravating men and causing their own pain. Even in the police station, the procedures favour those in power over Hava. The policemen believe that Hava must somehow be responsible for her own situation – that she is the one to be blamed.

A DJ at the back of the stage plays music whenever there is a change of scenes. Wearing his eye-catching, illuminated scarf and hat, he is present throughout the performance, from the hospital to the police station, until the end.

As Hava asks for help, this DJ turns up the music, in a scene that reminded me of a disco. One of the policemen, who is called “boss” by his sergeant, puts on his headphones and starts to dance. By correlating the music with Hava’s groans of pain, does Koliqi want to convey how the system feels about Hava and other women in her situation?

Hava is calm almost all the time, yet she still is able to ask the questions she needs answered; she is preoccupied by the fact that she is getting an infection and the policemen hush her with the all-too-often-heard bureaucratic statement: ”We’re the ones who ask the questions here, not you.”

Stiffler at Teatri Oda, Prishtina. Photo: Sovereign Nrecaj

I heard some giggles in the audience at this point and I wondered what they were giggling about. Are we so used to this kind of language in our institutions that we have normalized it, made it something to laugh about it? Because while the play showed the absurdity, the irrationality, the perversion of power and the vulgar truth of the situation, it had no fun in it.

Perhaps they were laughing from what they saw as being ridiculous in an absurdist way. It’s more than likely the audience has witnessed this kind of behaviour and language in public institutions, so it made them laugh. Or perhaps they thought such language is only used in plays?

The police station in which Hava finds herself is the kind of place that oppresses the vulnerable like her, pressing down on the victim’s heads, even when they are only trying to address their basic needs, their human rights.

It’s the kind of system that is familiar in Kosovo nowadays, as historic cases of injustice towards women are starting to emerge. The play’s relevance is evident, as it starts rubbing the dust from the forgotten files of the numerous women who suffered injustice at the hands of public institutions.

Doruntina Basha shows how the language used by these institutions is often unprofessional and derogatory. She emphasizes the way in which the officials communicate with each other. Hava is referred to as a slut and, instead of addressing her case, they discuss her private life, harshly judging her morals. They see her presence as no more than an infection.

Basha includes a flashback to Hava’s adolescent years, to when she had had an abortion when she was young. The gynecologist tells her to open her legs “because she knew how to do this somewhere else”, something that is heard a lot in Kosovo’s maternity hospitals.

After everyone fails Hava and the knife is still in her back, she asks for some help from her brothers. She finds them working in the butcher, wearing plisa (Albanian traditional hats). Just like everyone before, her brothers choose to insult her morality, to blame her for disgracing and dishonouring the family.

Hava wants to see her mother, but they tell her she is dead. She remains alone, confronted by a cruel society that indirectly wants her to perish because it can’t make space for her. A society that has created its own framework of morality and honour, while leaving humanity and empathy on the outside.

The play is particularly emotive in its last scenes, when Hava’s dead body ends up in a morgue. The fact she has died alone, with no one to come and ask for her, brings sadness to everyone’s souls. Even the morgue workers, who at the beginning of the scene seem to lack humanity, who seem oblivious to Hava’s corpse lying in the same room, are touched by this last powerful scene.

An ultrasound image of a baby that was never born is found in Hava’s pockets. Hava’s dreams and hopes are also dead, but in death, Hava awakens a new era of revolt – the voice of Kosovo women who will never stop fighting for justice.

Credits:

Author: Doruntina Basha

Director: Kushtrim Koliqi

Cast: Rebeka Qena, Adrian Morina and Armend Smajli

Florida is a lover of words, and of art in all its forms: fiction, poetry and drama.