This year’s Desiré Central Station Festival took place in Subotica between 25th and 30th November. Natasha Tripney reflects on a vibrant and varied programme featuring work by Andraš Urban and Máté Hegymegi.

The programme of the Desiré Central Station festival reflects the cultural mix of its home city. Subotica is a city in the Vojvodina province of Serbia famous for its whimsical art nouveau architecture. A large proportion of people speak Hungarian and the festival, which was founded in 2006, is based at the Hungarian language Dezső Kosztolányi Theatre, named after the famous Hungarian writer from which the festival also takes its name (his nickname was Desiré). The ‘station’ part refers to Subotica’s proximity to the border.

This year the six-day programme consisted of a mixture of Hungarian, Serbian, Slovenian, Croatian and Bosnian work, beginning with two performances by Hungarian director Máté Hegymegi from Budapest’s Studio K. The festival opened with Hegymegi’s version of Heinrich von Kleist’s Katie of Heilbronn, which I was not able to see, however I did catch his second production, and am glad I did.

Nero has been adapted by Judit Garai from Dezső Kosztolányi’s book The Bloody Poet: A Novel About Nero. Visually, it’s an incredibly distinctive production. Designer Anna Fekete’s set consists of a narrowing aperture, like the lens of an old-fashioned camera with a buttercup yellow interior. In its perspective- skewering dimensions, it brings to mind the entrance to the chocolate room in the 1970s movie Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. There’s even a tiny piano in place of a lute on which Nero occasionally bashes out a tune.

Attila Vidnyánszky jr gives a vigorous and highly physical performance as the teenage emperor and wannabe artist. His Nero is a swaggering would-be super-star, charismatic if brattish, frequently shirtless, clambering into the audience with his trousers down, effortlessly suspending himself from the ceiling by way of dangling straps, bemoaning the fact that someone of his poetic sensibilities would be better of being born Greek where they respect and celebrate that kind of thing. He is prone to toddler-like outbursts, but he is also sharp-witted and capable of reflection.

The play explores whether he was the cruel tyrant of legend who killed his mother and cared little for his people, or a more misunderstood figure overburdened with power at a young age, someone whose story has been eclipsed by myth. It asks whether poetry and power-lust can co-exist in the same soul.

Hegymegi’s production captivates for its entire three-hour running time, flitting between scenes of hedonism – Nero gobbling chunks of pineapple from the blade of a saw – to more contemplative, low-key moments. Hegymegi injects certain scenes with great tension. The death of Júlia Nyakó’s commanding Agripinna sees Nero shattering the chair on which she had recently been sitting with such force that pieces fly across the stage.

The death of Seneca, Nero’s advisor, on the other hand, is hypnotically slow, with Lajos Spilák, as Seneca, quietly relating his demise, accepting his own fate while shuddering on occasion as his life ebbs out of his veins into the bathwater.

The set proves surprisingly, delightfuly versatile. It contains various sliding panels and can be moved around the stage. In this way a potentially constrictive space is made a playground. Vidnyánszky acrobatically straddles the gap between the walls and he and the other actors sometime sit on chairs suspended from the sides. The set also suggests the insulation that Nero experiences from the public, cocooned in his own golden box.

As stylish and inventive as Hegymegi’s production is, it’s also a reminder of the effort we expend on decoding monstrous men, continually placing them at the centre of the stage, the centre of the story.

Solo at Desire Central Station Festival

While Mirko Radonjić’s production of Anna Karenina was unfortunately, cancelled, audiences were able to experience Nina Rajić Kranjac’s sprawling four- hour Solo – a well-chosen piece for the festival given the way in which it explores the complexity of post Yugoslav identity. Audiences were led through the streets of Subotica by a man in a Pink Panther costume and the performance’s second ‘Serbian’ section, in which the audience are fed cevapi, burek and wine around a long table as flames crackle in the background, took place in parkland next to the Jadran stage of the National Theatre, with fires burning to ward off the November cold as Marko Mandic scaled a fire escape on the side of the building. (For more on this performance read the SEEstage review).

The next night consisted of a double-bill of two Slovenian performances that both, in different ways, reflected on the impact that the pandemic had on the creative process and people’s emotional wellbeing in both form and content.

Vito Weis is a member of the ensemble at Ljubljana’s Mladinsko Theatre well known for the physical commitment of his performances. He always gives of himself whether cavorting with bells on his balls in Trimalchio’s Dinner or being repeatedly bound and gagged during Ziga Divjak’s Fever. In Bad Company, he performs alone, untethered from the ensemble.

The show, which, like Solo, originated at Mladinsko’s New Post Office space, starts slowly as Weis potters around the stage arranging and rearranging a series of folding chairs into rows, plugging and unplugging various cables hanging from the ceiling, before pausing to assess his progress or smoke a cigarette before undoing everything. It’s such a slow start that it generates this tense sense of anticipation as we wait – and wait – for a proper ‘beginning’. Gradually, these preparatory gestures, the readying of the space for a performance, become the performance. In this way Weis captures something of that weird limbo experienced by so many in the performing arts when deprived of an audience with no real sense of when that audience would return. In some ways it echoes Ontroerend Goed’s Every Word Was Once an Animal, a piece that also attempted to capture the frustrating stop-start nature and strange stasis that characterised the early part of the pandemic, but Weis’s show is more intimate and resonant than the Belgian show.

Occasionally the combination of atmospheric lighting and the arrangement of objects on chairs will coalesce to create striking compositions. And, in the final sequence. Weis gradually collects every chair, hanging them from his arms, from his neck, undertaking a task it seems foolish for one man to attempt alone. He collects chair after chair until he is laden like a human mule and his face gleams with sweat. It’s both a feat of strength and a potent image, one man shouldering everything until he collapses.

Vito Weis in Bad Company. Photo: Nada Žgank

This was followed by Oh How Very Ordinary, a dance theatre piece from Bojana Robinson and Katja Legin. Instead of creating a duet as they might have in normal times, they have created something that resembles a diptych drawing on personal experience with interjections from other artists. In the first section, Katja Legin performs a dance full of humour and mischief inspired bt a memory of her grandmother. She sits in an armchair and, to the strains of Benny Goodman and Ella Fitzgerald, kicks out her legs out with such vigour that she loses a shoe. She struts and shimmies like a woman gloriously at home in her own body. She glints and winks at the audience, as she dispenses glasses of fizz and blitzes tomatoes in a soup pot, performing this domestic task with a very sexy chaotic energy, before sending tomatoes cascading over the stage.

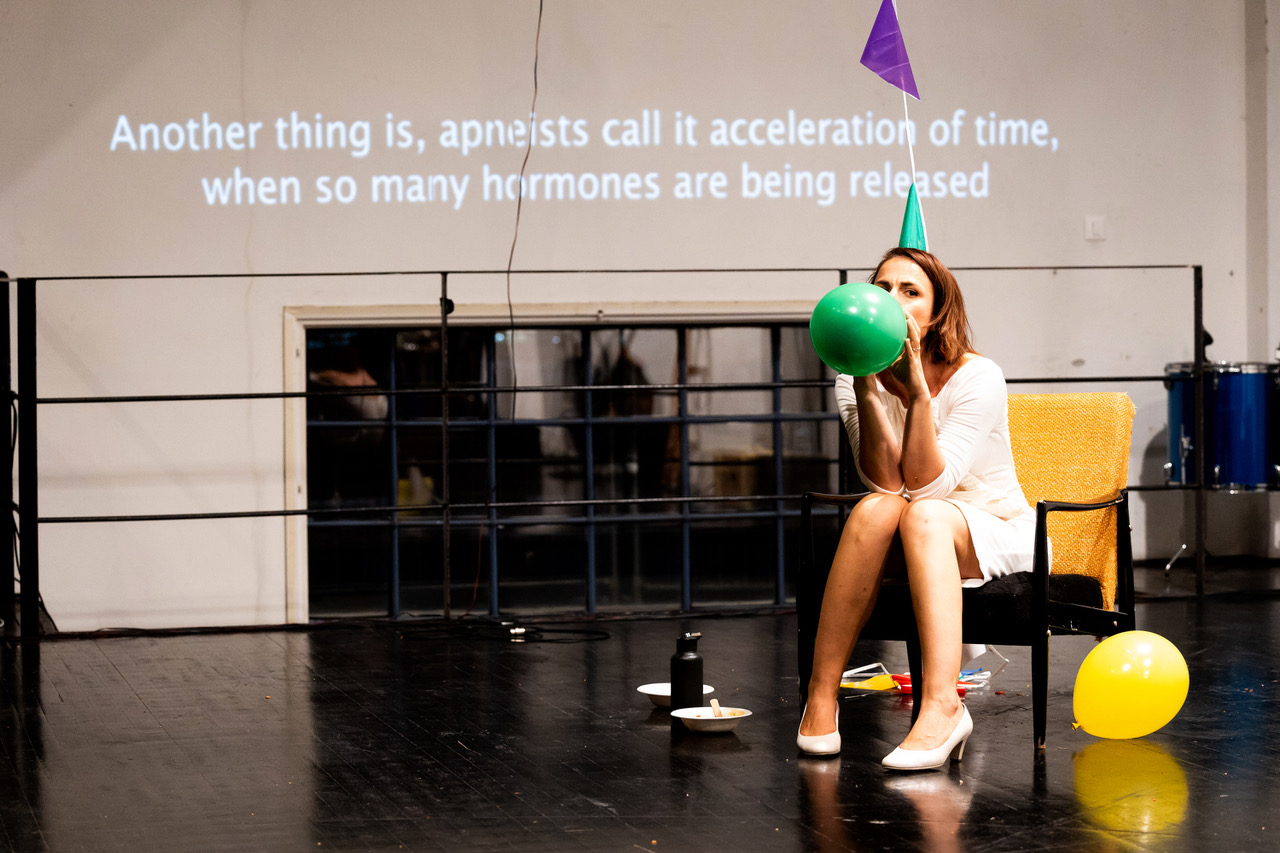

Bojana Robinson’s piece is, in contrast, less exuberant and more layered. It is inspired by her experience of living with a child with health issues, meaning her and her husband were already acutely aware of her daughter’s every breath and the need to protect themselves from potential infection, before the outbreak of Covid-19. Clad in a short white wedding dress, she blows up a series of balloons and sprints in circuits around the stage, and beyond into the backstage areas and up and down the stairs into the galleries above, so that she and we become aware of her breathing, of the effort involved in every intake and exhalation of air. Robinson sits and listens with a sense of fascination to an interview with a Serbian free-diver as he describes the sense of bliss that accompanies hypoxia. At one point she calls up Nina Rajić Kranjac who sings down the phone. She also dances loosely and freely, a sequence that feels like a release – a breather in a performance concentrated on breath. It’s a touching, intimate and personal piece, in which Robinson uses her body as a dancer to explore our shared fragility, finally struggling to blow out candles on a birthday cake.

The production contains a third sequence, a contribution from musician Tomaž Grom featuring video and jagged music which acts as a sort of prologue but gets a bit overwhelmed by the pieces that follow.

Bojana Robinson in Oh How Very Ordinary. Photo: Marcandrea Bragalini

These two meditative pieces were followed by Ibi the Great, the cacophonous and shit-flecked excess of festival director Andraš Urban Urban’s own metatheatrical take on Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. After an opening monologue in which one of the cast insists that a play about Polish Catholics can shed no light whatsoever on our current situation and we’d be stupid to even think this was possible, the performance launches into an intensely scatological, often uproarious two hours performed by a talented and committed cast who occasional pause between enemas and explosively emptying their bowels to reflect on why they make and love theatre – with one female performer wearily reflects on how often she has been obliged to take her clothes off. Borisav Matic’s excellent review describes this show in more detail.

The final night started with Screenagers Vol 2, an endearingly lo-fi one-woman show performed by Barbara Matijević and made up of a mixture of observations, animations and songs about life as a first-generation digital native. The catchy, synth-y tracks explore the way the internet fuels our anxieties, how a diet of listicles and hastily churned out life-hack content regularly instructs us that we’re doing things all wrong: sitting wrong, eating wrong, breathing wrong – that we suck at the business of living.

There are witty Instagram montages (video by co-director Đuzepe Čiko) which demonstrate how social media has eroded originality in our quest to turn every life experience into a shareable moment. We watch a string of images of people taking beach selfies, airplane wings framed against the sky, couples cutting wedding cakes or people pretending to pinch the sun between their fingers, each very similar to last, a copy of a copy of a copy.

Matijević frequently interacts with her laptop, essentially turning it into an extension of her body, her arm merging with an image of her hand on screen. Later she encourages the audience to join her Wi-Fi network and collaborate on one of the musical numbers. Though the show doesn’t dig all that deep into the psychological and socially ramifications of increasingly living our lives online, it has real charm and wit and Matijević is a very engaging performer.

A Hunger Artist. Photo:: Velija Hasanbegović

The closing production of the 2022 festival was A Hunger Artist by the National Theatre of Sarajevo. Drawing on Kafka’s life, works, letters and diaries for inspiration, it is not a standard literary adaptation, instead it subverts the form, using Kafka’s story – about a man who starves himself in front of an audiences only to sees his efforts go underappreciated as tastes in entertainment – as a springboard.

The cast clad in matching white trouser suits riff on both the story and on Kafka himself, as a man and an artist. But he makes for troublesome subject, rigid and cranky and bored by anything unrelated to his art.

The show, directed by Alen Šimić with dramaturgy by Benjamin Hasić, starts out as a playful and engaging verbal performance in which each company member introduces themselves by name and describes their relationship with their work and what it means to make theatre. They also discuss what theatre means to the people of Sarajevo (to many, not all that much). They each have a turn to speak – some while hanging from a circus hoop – before the show switches mode about half-way through, evolving into a dance piece in which the cast chant Kafka’s name while bouncing up and down and marching in unison, before forming a kind of human caterpillar, each resting their body on the person in front, as if they were one single organism, the lines between them blurring. They repeat this routine in various formations until they are visibly knackered, and the repetition has become as gruelling for them as us.

So much of the work in this year’s programme has contained some sort of reflection on theatre itself, a sense of existential wrestling from theatre makers reconnecting with live audiences after a period of isolation, while interrogating what theatre means. Watching the whole programme is like watching an artform staring at itself in the mirror with the same intensity as an adolescent, inspecting every blemish, but at least A Hunger Artist ends in a positive place, with a sense of hope and a faith in beauty.

Main image: Nero – photo by Laslo Vaš

For more information visit: DesireFestival.eu

Further reading: review of Solo

Further reading: review of Ibi the Great

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0