The Slovenian director Sebastijan Horvat recently staged Heiner Muller’s Cement in a project encompassing three theatres with three different ensembles. He spoke to Natasha Tripney about this ambitious undertaking and the centrality of design in his work.

Natasha Tripney: What first drew you to this play, to Heiner Muller’s Cement?

Sebastijan Horvat: It was a big coincidence. I had the text by Heiner Muller lying on my desk for two years. And then I read it and I was really astonished that in 1972, he was giving a critique of the leftist project from the East Germany perspective. [The play is] not saying that the revolution and the leftist project is bad. It’s just saying let’s critique it. This perspective was very interesting to me, because we now know that East Germany had a very difficult communist regime. You cannot compare this regime, with the Stasi, to the Yugoslavian situation. We could travel around. For me, it was interesting position from which to have this critical perspective on the leftist project. Because I consider myself as on the left, maybe even the radical left, but I still want to know everything about the rise of the left regimes in this century.

Natasha Tripney: How did you come to make it in this way? In three parts at three theatres with three different ensembles?

Sebastijan Horvat: I got invitations at the same time from the National Theatre in Slovenia, the Youth Theatre in Zagreb, and the Belgrade, Drama Theatre. And I thought: it’s easy to criticise the contemporary situation, neo-liberalism and so forth, but let’s try and say something about this common project called Yugoslavia. Let’s bring Yugoslavia together again on a cultural level, without getting into nostalgia and without getting into the idea that everything connected with Yugoslavia was bad. Let’s start a discussion about what was good about it, and what was bad about it. And all the artistic directors said yes. From the beginning we agreed there would be three segments and three Cement festivals in which all three parts would be played.

Milan Ramšak Marković was my very close collaborator on the whole concept as well as the playwright of this last segment in Belgrade. And we also had the same creative team for all the performances: the lighting, the design and everything

I like to think about these three segments as the three acts of one play. The first act was done in Zagreb. And then the second act in Ljubljana and the third in Belgrade. If you only watch one, it works, it is okay, but the third performance refers back to the first performance. It closes the circle.

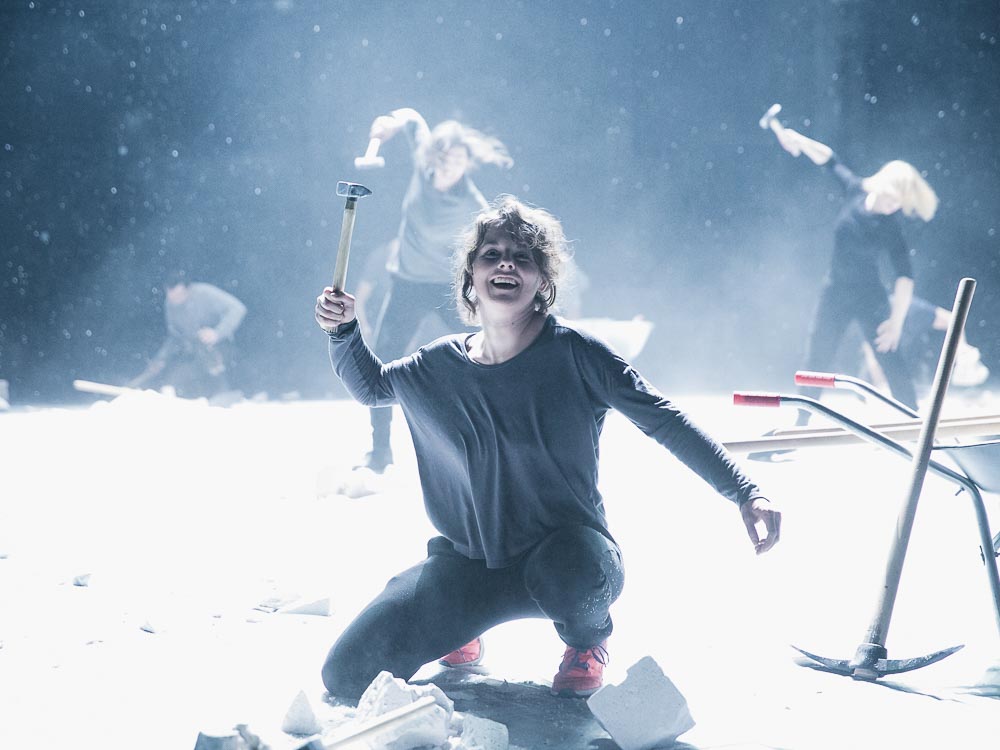

Cement Zagreb

Natasha Tripney: What is Muller’s play about?

Sebastijan Horvat: Cement is based on the novel by Fyodor Gladkov, which was written in the 1920s, after Lenin’s New Economic Policy, which turned the state towards private initiative. This is a really interesting moment in the history of Soviet Union in which they allowed private interest in farming and small businesses. Lenin got strongly criticised because of this but it stopped big hunger from coming. The whole play is about what happens when you let some capitalism in this communist idea, when you open a small door or a window. There was also a very strong feminist movement at this time.

The story is based on the relationship between Gleb and Dasha. He’s a big revolutionary on the outside, but inside, his wife is telling he is still bourgeois male who wants to possess a woman. There is a big fight inside him because he wants to change.

Natasha Tripney: How do the three segments differ stylistically?

Sebastijan Horvat: The whole play is still very interesting today [in respect of] the question of women’s rights and feminism, especially the last conversation between Dasha and Gleb where she says I love you, but maybe we must reinvent the word love, like we did with social relationships. We have to reinvent love.

The first part [Cement Zagreb] looked at these big dramatic pictures and narratives from the play from the historic position. The collective movements, people running factories by themselves, and so forth. We performed it with 13 or 14 young actors.

The second part [Cement Ljubljana] is something completely different. While he first part was big, the second part is small. Everything takes place in one apartment. It consists of only three scenes. The text is very large. We out only everything out and left only relationship between Gleb and Dasha. It’s not so classically dramatic like the first part. It is strange and alienating.

Natasha Tripney: And the third part?

Sebastijan Horvat: The third part [Cement Belgrade] is a commentary. It’s taking place now, today. The first part is taking place in the 1920s, In Russia, the second part is taking place in the 1950s. And then the third part is taking place now, in Belgrade.

Natasha Tripney: Cement Belgrade is divided into two very different parts – one a vibrant dance sequence, one a more realist piece of theatre. What was the intention here?

The idea with the first part is to talk about young people. Let’s put some young people on the stage. And let’s put text in their mouths which is full of hope about the future. Let’s imagine that this is possible without any cynicism, sarcasm or irony. Let’s really believe that we can change the world without the baggage of the communism of our parents. Let’s give them the power. Let’s use contemporary music. Let’s show them that we are young, and we believe and there is so much freedom. This is a dance part which they learned in one month using an improvisation technique done by [choreographer] Ana Dubljević. What she did is really amazing.

With the second part we confront life in Belgrade today through this older couple. From the beginning Milan and I were talking a lot about dementia. All these nations in the former Yugoslavia have this dementia. We are constantly forgetting stuff, and we would like it to not exist at all.

The second part is aggressively realistic. Torturous. It is so slow. At one point someone is crawling on the floor and they are really crawling. We do not speed it up.

Cement Belgrade

Natasha Tripney: The construction of the set, which occurs midway through the performance with the actors on stage, is very central to this production.

Sebastijan Horvat: [Designer] Igor Vasiljev is a really important part of my group. I think the set design is sometimes the most important dramaturgical element, the most important possessor of the meaning of the performance or its politics.

Natasha Tripney: This was true of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul, you adaptation of the 1974 Fassbinder film.

Sebastijan Horvat: There was an extremely strong emotional moment [in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul] when we invited people to build a house for the characters in the intermission, to build a house together for this beautiful love between a refugee and an older lady, and we put some music on from the 70s and 80s, from when everything was still possible.

There were working brigades in the former Yugoslavia. My parents built the highway from Rijeka to Split. They were working for free, but they were having a beautiful time. They were young and they were all the time having parties. They were dancing and singing and falling in love. They were working for a common goal.

Natasha Tripney: That piece was also like two different performances.

Sebastijan Horvat: I really like these different perspectives. I really like it when you start watching the performance and you understand it to be one thing. You think you know what it is. You think you have the apparatus to watch it. And then something happens and everything is destroyed in the middle of the performance. You have to re-establish how to watch it. Something similar happens in Cement Belgrade.

Natasha Tripney: You were telling me there’s now a fourth piece in the Cement project.

Sebastijan Horvat: Heiner Muller was a postmodern playwright. And in this play, he combined the contemporary moment with the historical moment of the Russian Revolution with monologues from antiquity. There is a very postmodern moment where the hero Hephaistos defeats Hydra, the monster with many heads and when you chop one off, you get two heads, and you cannot decipher from the text whether the Hydra is a neoliberal concept or the Stasi. It is brilliant and it was a strong inspiration from the first to the third segment, but we constantly cut it out. We didn’t use it. But then we decided that since we had done almost the whole text and the commentary, we would do Hydra. To complete the tetralogy. But, also, to do something that is completely different.

Natasha Tripney: Tell me about this fourth instalment. In what way is it different?

Sebastijan Horvat: Muller’s play is about a cement factory, but in all three parts we don’t ever see the factory, so we said, okay, let’s go to the factory. Let’s see if this factory exists in Slovenia today. We wanted to take photographs of the workers working these jobs, but we had a lot of problems because we couldn’t get permission. Eventually we found somewhere where they allowed us to take photographs of workers making these highly sophisticated chips and electronic devices. But everything else around them was so old fashioned, so strange, so loud. It was shocking to me.

We played a movie made up of these still photographs of the workers throughout the performance as six dancers dance on six spots, running and doing a lot of crazy stuff, but always on the spot. There is also text and music.

Natasha Tripney: What is the situation like for artists and the arts in Slovenia following this year’s elections?

Sebastijan Horvat: I think the Minister of Culture is an educated person and understands that culture in Slovenia should not only be connected with the contemporary situation but that there should be some independence. I think it is extremely important to maintain this balance. Right wing parties are always putting money into cultural heritage and art is not so important [to them]. I strongly believe that critical contemporary art should be subsidised. Of course, not everything will be good, but if you produce a lot of things, some good will emerge. However, I must say I think the most important thing today is the fight for independent television. s is something what is still under control of right-wing people who were put in their positions during Janez Janša’s government. This is important and that fight is still going on.

Natasha Tripney: And next year you will direct Brecht’s Fear and Misery of the Third Reich for Mladinsko theatre?

Sebastijan Horvat: This is a project about fascism today, about populism and the far right. A lot of young people are really connected with the alt right as a kind of new punk. Giorgia, Meloni said if you want to be a rebel, you have to be conservative. They have appropriated the concepts of transgression and counterculture. Historically, communists didn’t realise what a threat fascism was. They couldn’t compete.

Main image: Dragana Udovičić

Sebastijan Horvat’s production of Fear and Misery of the Third Reich will premiere at Mladinsko Theatre in January 2023

Further reading: Žiga Divjak interview: “We have to completely change our value system.”

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0