Robert Lenard, artistic director of Novi Sad Theatre, talks to Borisav Matić about the importance of interculturality, the current state of the independent scene in Hungary and his cabaret based on Foucault.

Borisav Matić: Novi Sad Theatre occupies a very specific position in the Serbian scene because it is the theatre of the Hungarian national minority in Serbia. How do you see the role of the theatre?

Robert Lenard: Since I have been in the position of artistic director, I always tried to re-read our original statute and foundational act which very precisely defines the role of Novi Sad Theatre.

It is the theatre of the Hungarian minority but at the same time it is a city theatre which is very important in identification for me because that doesn’t bind us to some national or folk theatrical qualities – it binds us to the role of a city theatre which is a role that has developed in interesting ways in Europe over recent years. I’m thinking of Milo Rau’s Ghent Manifesto, which is a city theatre manifesto.

It’s important to note the Hungarian language is not as present in Novi Sad as it was in 1973 when the theatre was founded, exactly 50 years ago – that dynamic is changing. Thirdly, Novi Sad Theatre was founded as an experimental theatre. That’s a key part of its foundational act.

The first premiere at Novi Sad Theatre in 1974 was the Cat Game by István Örkény. That’s now a classic in Hungarian literature – a bit absurd, a bit realistic – but that play was written two years before the foundation of Novi Sad Theatre. At that moment, it was a contemporary Hungarian drama. I’m not saying that it’s revolutionary, but it was very contemporary. Later it became a theatre that didn’t deal that much with reality and new forms but with classics. That was also determined by the fact that many of the actors left and fled the war. A completely new generation emerged at the end of the 1990s and that formed the theatre in a different way. But the original idea of Novi Sad Theatre was always what I think it is aiming at today, to be a contemporary theatre, a bit experimental, to be the city theatre and to be the Hungarian theatre – all at the same time.

Borisav Matić: When it comes to the relationship to national culture, do you envisage the theatre more as an institution that should nurture Hungarian culture in the majority Serbian environment or as a place for intercultural exchange between Hungarian and Serbian theatre culture?

Robert Lenard: That’s one of the questions that I think we should consider more thoroughly. Of course, we’re talking as if only I influence that, but the director of the theatre mostly has influence. In this case, it’s Andras Urban. I think that he is thinking about how to make the theatre a bridge between two cultures. We have Simović’s Travelling Troupe Šopalović on the repertoire at the moment, we have Vojvodina’s contemporary Hungarian dramas, we also have Hungarian classics, and we’ll have some authorial projects. We have a little bit of everything, but I think there should be an intercultural environment, if nothing else, by virtue of the choice of texts and directors.

Borisav Matić: Regarding interculturality, we must also consider cultures other than Hungarian and Serbian. Novi Sad Theatre organized five annual editions of the Synergy Festival, an international festival of theatres that are in the minority in a national or linguistic context. The festival is a form of cooperation with minority theatres from other countries. How important is that in your work?

Robert Lenard: Somehow we have primarily fostered relationships with theatres that work in the Hungarian language but outside of Hungary. We have much more in common and a much better understanding with theatres, for instance, from Romania that work in Hungarian, in respect of both the theatrical language and more general observations.

There is something called problematic alt-shift. Nobody understands that except us. No one who is part of the majority culture needs to change the language on the keyboard. But I need to change the language during a single sentence sometimes. I’m writing in Hungarian but have to write some names in Serbian. Automatically – alt-shift, I change the language to Serbian, write that name, change back to Hungarian and move on. That’s a typical problem that Hungarians from Romania understand as well as I do.

Borisav Matić: Looking beyond Novi Sad Theatre, you have a very good overview of the theatre culture in Hungary and Serbia, because you work in theatres in both countries. How would you compare those two theatre cultures?

Robert Lenard: I worked recently on the independent scene in Hungary which is different from institutional theatre in terms of style, comfort and courage. You have very few institutional theatres in Hungary that allow themselves the luxury to experiment in any way. I won’t say that institutional theatres are industry because they are trying to get the job done honestly. In Serbia, even the National Theatre allows itself the luxury to bring Boris Liješević, for instance, or the Belgrade Drama Theatre to bring Frank Castorf. Hungarian institutional theatres rarely allow themselves something like that, especially if they’re not based in Budapest.

Borisav Matić: Is there a big difference in terms of political themes, as well as aesthetics?

Robert Lenard: There’s the question of funding. Budapest is in the opposition’s hands. But only Budapest and maybe a few more towns – Orban has mainly lost Budapest. Theatres that are financed through the city budget are a little bit freer concerning that matter.

I think that there is a general fear in Hungary. The independent scene is in a very interesting position there. They do not get money. Theatres in Hungary annually get a surplus donation from the state which, in theory, is awarded according to the number of the audience. I’m simplifying things – I won’t explain the Hungarian system and its history and where this comes from – but a lot of excellent troupes that existed for 30 years got zero forints in that competition. That’s crazy. They are literally on the verge of ruin. Despite that, or maybe because of that, they are the bravest companies around – not just in the critique of this government but generally in society.

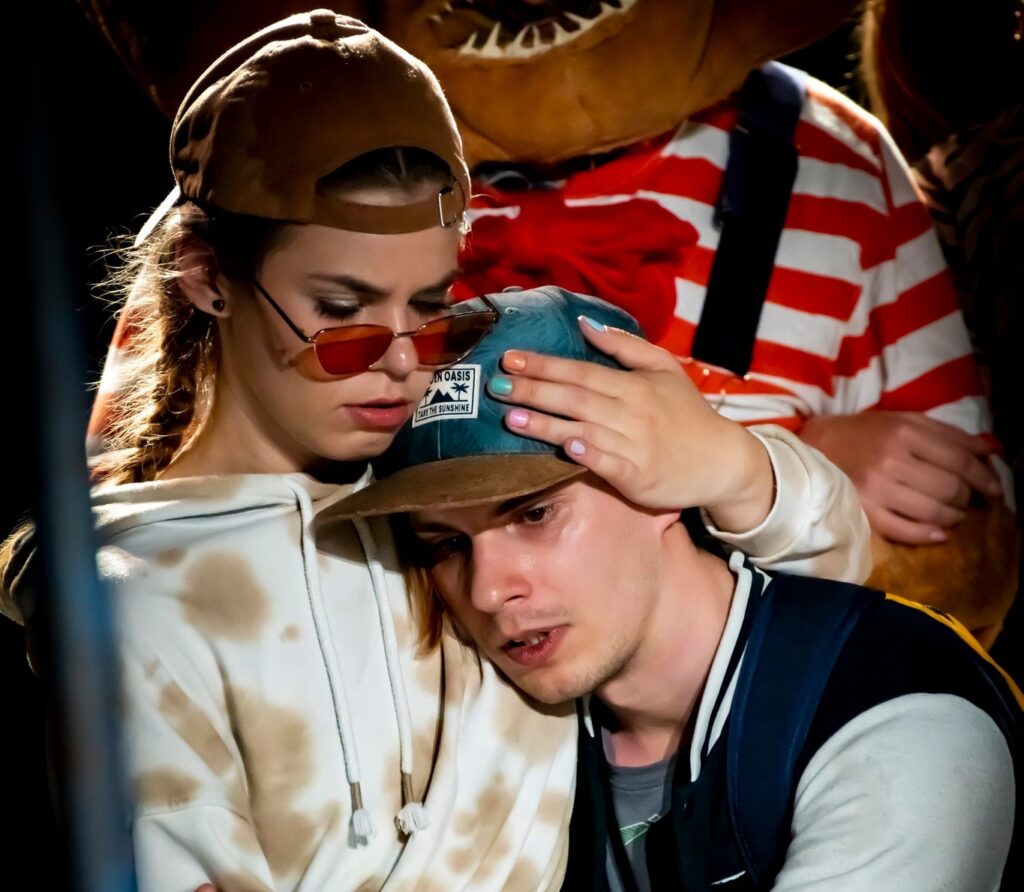

The History of Sexuality Photo: Eva Juhas)

Borisav Matić: In March this year, you directed a production based on Foucault’s The History of Sexuality at TÁP Tilos az Á Performansz Színház, an independent theatre in Budapest. We know that LGBTQ rights are increasingly under threat in Hungary and that it’s increasingly difficult to speak about the topics of sexuality…

Robert Lenard: It’s not. You can speak about everything, it’s just that it automatically belongs to the category of 18+, even if you don’t have nudity, foul language… That’s the problem. It’s literally the same law as in Russia. The most problematic term in the law is the propagation of LGBTQ values or ideology, as they would call it. They call it gender ideology. When the Hungarian government speaks about that, they either don’t understand or stubbornly refuse to understand the term ‘gender.’ By gender they mean, for instance, transgender people in transition.

What does propagation in that law mean? Does it mean that I’m showing in a positive light a gay person or is that a public call to have surgery and change gender? Or, generally, any talk on those subjects. It’s not clear in the context of that law in Hungary what that exactly means, just like it’s not in Russia. That’s a term that’s very susceptible to manipulation.

We didn’t go very far in the performance in dealing with that law. Everyone on the independent scene in Hungary is dealing with that law – there are a lot of shows on that topic. Secondly, our performance deals with a much wider theme.

Borisav Matić: When talking about Foucault’s ideas, what did you mostly focus on in the performance? How does the performance communicate with the ideas from the book?

Robert Lenard: If I wanted to define the performance in genre terms, it was more like a cabaret. We worked in the following way: we read Foucault and tried to single out some of his ideas, and then tried to find today’s counterpart because he died in 1984.

One example: he didn’t engage at all with pornography. We thought that it is an important subject, because in his time, if you wanted to watch a porno film, you had to go to a certain cinema in Paris, and then you were a little embarrassed to get in… You had that whole process. Today, everything is one click away and that’s a societal problem.

We had discussions on each subject. We discussed the normalization of BDSM, the non-normalization of someone else’s sexuality… Foucault calls that state racism – our sexuality is cool, and someone else’s is not cool. We just transferred that to migrants. You don’t have to imagine any enormous theory behind that, we simply searched some 200 articles from the Hungarian national press and portals where there’s a piece of news about how a migrant raped a girl. We found around 200 examples!

Borisav Matić: The History of Sexuality is a very complex theoretical work, yet you managed to dramatize it and present it in a performative language mainly through cabaret and songs?

Robert Lenard: Yes, and through humour. But again, we went beyond the pretext material because Foucault wasn’t even able to dream about certain things that later happened, like the normalization of BDSM. Foucault considered BDSM as an exit from the machine of sexuality, that it is a negation of the system. Today, it is in the system. For example, we also dealt a lot with woke and cancel culture.

Borisav Matić: What is your approach toward woke culture in the performance?

Robert Lenard: We’re not talking about the whole of woke culture. We’re not interested in racism in that sense, only in sexuality. There’s one scene where an actor sings a song and the others stop the scene and say – Sorry, if you’re not a trans-person at least 51 percent, you cannot sing that to the end. And of course, a debate about the topic begins. On one hand, representation is legitimate; on the other, I think that we are overdoing it with all the quotas. I believe in Fassbender who said when they asked him why he has that many gay characters in his films, that he has precisely as many such characters as there are in society – 10 percent of his characters are gay or bisexual.

Borisav Matić: With Generation Z and beyond, the percentage may need to be increased.

Robert Lenard: It may need to be increased, it’s okay for it to be increased. But we’re talking about Netflix which currently has at least one trans character in almost all of its series. Of course, they were underrepresented but their presence in society is even now around 2 percent, for instance. We’re trying to fix underrepresentation with overrepresentation.

Borisav Matić: Is that necessarily a bad thing?

Robert Lenard: I don’t say that it’s a bad thing. The fact is that it is happening. But that’s not my biggest problem when watching Netflix, let’s face it. I don’t turn off a series because of that.

Borisav Matić: We mentioned the question of genre – The History of Sexuality is presented in a cabaret form. What I think is interesting about your work is the play with genre and with the dramaturgy of film. There are several of your performances where such patterns can be observed. Where does that influence come from? Is it because you studied both film and theatre directing at the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad?

Robert Lenard: I don’t believe it’s because of that. I think that my generation grew up more on films and TV series than theatre. Even writers that I read – Marius von Mayenburg whose work I did way back at the academy – write very short scenes that overlap with each other. That probably had an influence.

Everyone says that about my work but I don’t think so. For me, my work is theatrical.

Invisible Children. Photo: Srdjan Doroski

Borisav Matić: There is a theatrical language but I think that it is at least inspired by some elements of the cinematic. Let’s take for example your performance Invisible Children at Novi Sad Theatre, written by Ana Terek. On one hand, it’s a coming-of-age story about two teenagers who are existentially lost, but the story is told through the format of a road movie and as the performance progresses, it gains thriller elements. We have a very stylized story that may seem at the beginning as a naturalistic story from a place in Vojvodina.

Robert Lenard: It’s true but I don’t know how much that is intentional. I am a horror and thriller fan, by the way. When you say film dramaturgy, I’m always thinking about the dramaturgy of video editing or something like that, not necessarily about film genres. Peer Gynt is a road movie. I didn’t come up with that.

Borisav Matić: Invisible Children is a performance based on a contemporary text, unlike the last few performances that we have discussed that are based on classics or on a theoretical work like The History of Sexuality…

Robert Lenard: I like diversity. I also did Edward the Second, though I think it’s one of the worst shows I’ve done. Some decisions are not made just by me. For The History of Sexuality, a critic from Budapest asked me, if I could direct anything, what would I do? I said I would try to create something from a theoretical work. That was interesting to me, how that is even possible. As an example, I mentioned The History of Sexuality, book one. That information came to particular people who asked me very seriously if I would do that. And I said yes, let’s try.

Borisav Matić: Novi Sad Theatre often collaborates with acting students from the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad, from the Department of Acting in Hungarian Language. You recently worked with them on the performance Tanz! which you directed. What relationship do you think that city theatres should have with academies and students?

Robert Lenard: First of all, I have a stupid response – the students at the Academy are 200 meters from Novi Sad Theatre. It would be foolish not to utilize them, not to say to exploit them. They are happy that they are playing, we’re happy because they are active. In Hungary, there’s a practice in the third year of dramatic academies, for the guest director to come and create a certain project with that class. I always liked that.

I was talking about that practice with one professor of acting at the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad at the time who said – OK, what don’t you direct a performance with third-year students? That’s how we came up with the project Catcher in the Rye which went surprisingly well. We played that on the small stage at Novi Sad Theatre as an independent project, not as the project of Novi Sad Theatre.

Suddenly, the performance started to go to various festivals, from Romania to Hungary and picked up plenty of awards. The feeling was great, even more so because the performance was minimalistic – no scenography, very few costumes, almost no props. We created a performance of an hour and 10 minutes and wanted to see if it would succeed. No matter if it doesn’t succeed – money wasn’t invested, the energy was but surely we will get something from that, even if the project doesn’t succeed. But the project suddenly succeeded. That was the trigger to work fwith other students.

Borisav Matić: What’s the experience of the students who act in those performances? How much is that experience important for their later career?

Robert Lenard: It depends on the project. I was extremely glad when Tanz! premiered. We called every Hungarian director from Vojvodina and some came to the performance, which was great. But that isn’t the goal. If it happens, I’ll be very happy. But that’s not a way to “sell” the students, it’s more a way to work outside of the Academy – it’s not an exam, there’s no feeling “oh, we’re doing this for a grade”.

We want to have a project that’s simple to handle but is interesting enough and we can have the feeling of success. I remember when we went to the festival in Kisvarda with the Catcher in the Rye. We were in the student program, of course, the off-program. But there were also awards and round table discussions, with the same jury as for the main program. They got magnificent critiques and the award for a collective play. I hadn’t seen happier people in my life. For the first time, they experienced success and happiness in their work – someone told them that they were good.

Main image: Srdjan Doroski

For more information on Novi Sad Theatre, visit: uvsvinhaz.com

Borisav Matić is a critic and dramaturg from Serbia. He is the Regional Managing Editor at The Theatre Times. He regularly writes about theatre for a range of publications and media.

He’s a member of the feminist collective Rebel Readers with whom he co-edits Bookvica, their platform for literary criticism, and produces literary shows and podcasts. He occasionally works as a dramaturg or a scriptwriter for theatre, TV, radio and other media. He's the administrator of IDEA - the International Drama/Theatre and Education Association.