Director Oliver Frljić talks to Borisav Matić about the LOST – YOU GO SLAVIA season at the Maxim Gorki Theatre, the history and legacy of Yugoslavia, his new production of Frankenstein and the role of theatre in times of political crises.

Now the co-artistic director of the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin, Oliver Frljić conceptualized the 6th Berliner Herbstsalon together with the theatre’s artistic director Shermin Langhoff and Johannes Kirsten. LOST – YOU GO SLAVIA, the 6th Berliner Herbstsalon at the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin, set out to analyse the bloody dissolution of Yugoslavia and to explore its connection to our current moment.

Borisav Matić: A lot of crises are currently happening around the world, including multiple wars and the continual rise of the far right. Why is it so important in this political moment to examine Yugoslavia and its break up?

Oliver Frljić: Yugoslavia was the first – and currently the only – historical sequence in which various – not only South Slavic – nations were unified through antifascist struggle. It is also the first genuine political representation of the working class within the geopolitical context of South-Eastern Europe. In terms of gender politics, it represents the rupture with previous patriarchal models. In 1942, the Anti-Fascist Front of Women was established, boasting more than two million members. Jasmina Tumbas writes that women were legally deemed equal to men in August 1945. Additionally, “lesbian sex was decriminalized as early as 1951 (and homosexuality by 1977), abortion was legalized in 1952, and by the 1950s, paid maternity leave and the right to divorce were socially and legally accepted”. Through the foundation of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in 1961 – one year before the Cuban Missile Crisis and in the same year in which President Dwight Eisenhower warned of the increasing power of a »military-industrial complex« – Yugoslavia rejected the logic of a bipolar world in its search for new means and constellations against old imperialistic aspirations. As part of NAM, Yugoslavia was also the first European country to actively work on decolonization and the political subjectivisation of former European colonies. I personally see my contribution to this exhibition as performative resistance to a Western-centric, reductionist perspective that operates solely within the confines of established stereotypes of Yugoslavia.

BM: Throughout your theatrical work you have been sceptical of the idea of a nation and sharply critical of crimes done in the name of individual nation-states. Yet, the Yugoslav idea is seen through a much more benevolent though also critical and parodic perspective in your performances. What is it in the concept of the Yugoslav nation that makes it more progressive than others?

OF: The concept of a Yugoslavian nation is based on the belief that the South Slavs, including Bosniaks, Croats, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Serbs, and Slovenes, as well as Bulgarians, are part of a same nation despite diverging historical circumstances, languages, and religious differences. However, this concept has been discriminatory towards non-Slavic nations in Yugoslavia, particularly Albanians. The Yugoslav nation was unsuccessful in creating a new overarching identity that could absorb national tensions. Before the outbreak of the Yugoslav War, most Yugoslavs reverted to their ethnic and regional identities. According to the 1971 census, there were 273,077 Yugoslavs, accounting for 1.33% of the total population. The 1981 census recorded an all-time high of 1,216,463 Yugoslavs, representing 5.4% of the population. If we examine the population of Yugoslavs in post-Yugoslav countries, Croatia reported only 331 individuals (less than 0.01% of the population) compared to the 1981 census, where Yugoslavs comprised approximately 8.2% of the population in Croatia.

BM: The Yugoslav idea is also characterized by a contradiction – striving towards socialism and internationalism, yet eventually closing into a concept of a South Slavic nation-state that marginalized minorities, Albanians in particular. What do you make of this contradiction?

OF: The question of the status of Kosovo and the Albanians is where Yugoslavia undoubtedly failed. This failure resulted from both national and economic negligence. For instance, in 1975, Kosovo’s per capita income was only 33 percent of the Yugoslav average. Additionally, due to the significant size of the Albanian ethnic group in comparison to other Yugoslav nationalities and population of Albania itself, it was unacceptable to treat them as a national minority. On April 2, 1981, large protests occurred in the Socialist Autonomous Province of Kosovo, demanding republican status within the Yugoslav federation. Underlying request of this protest was the acknowledgement of their equality with the Slavic nations by establishing their own republic, with the additional condition of participating in the Yugoslav community of nations on a completely voluntary basis. The following day, the Army intervened with tanks and armoured personnel carriers to impose martial law, marking the first instance since 1945. The country waged war against its own citizens which some believe initiated Yugoslavia’s dissolution. Any comprehensive examination of Yugoslavia must acknowledge those contradictions.

BM: With rampant nationalism and neoliberalism in ex-Yugoslav countries, can positive examples of Yugoslav heritage help us bring hope in social change in the region?

OF: I am sceptical of the possibility of societal transformation. Jelena Vesić has interpreted the war in Yugoslavia as a conflict driven by capitalism and the privatization of social property and resources, intertwined with ethno-identitarian ideologies promoted by nation-states, paramilitary alliances, and international legal institutions with colonial logic. Failing to label this ongoing conflict, where class identity was the first casualty before giving way to national identity, is a significant setback. Yugoslavia has been demonized to normalize this abnormality. The primary tenet of this normalization asserts that everything was significantly worse in Yugoslavia. Such characterization constructs a negative perception of Yugoslavia and precludes any productive, non-derogatory discussion regarding its history.

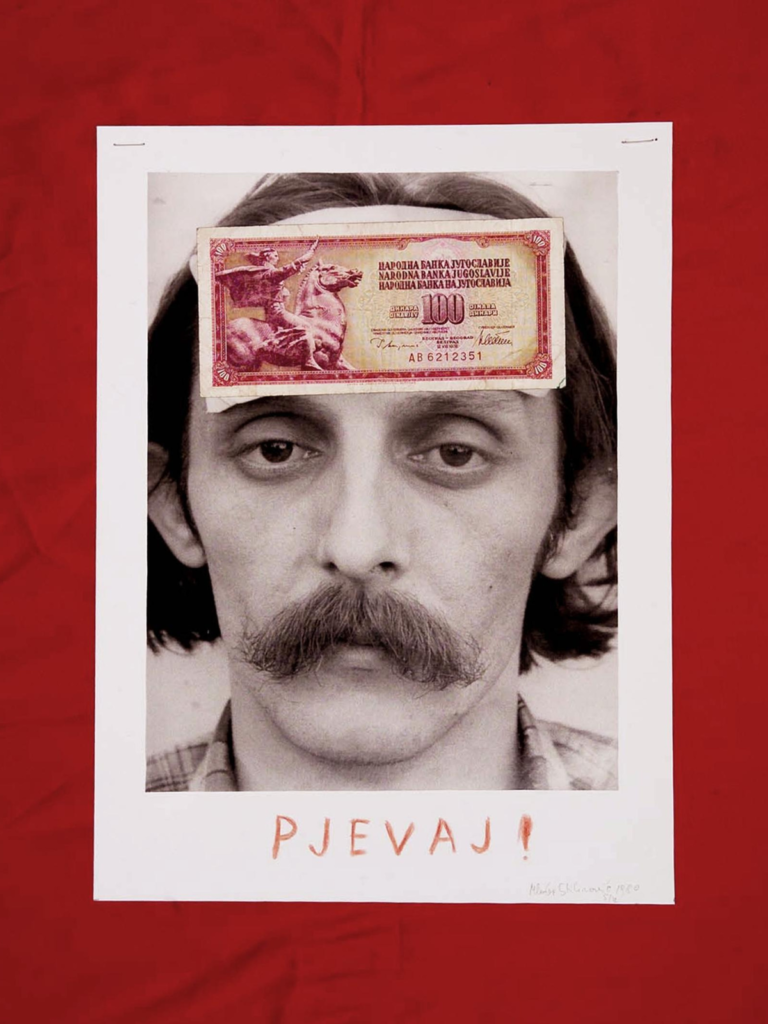

LOST – YOU GO SLAVIA Mladen Stilinović

BM: How did you select the works for this year’s Berliner Herbstsalon? What idea do you want to communicate through selected works?

OF: Guillermo Gómez-Peña writes that “North stereotypes the South. In turn, the South internalizes these stereotypes and either reflects them back, commodifies them to appeal to the consumer desire of the North, or turns them into ‘official culture’.” In that sense, I have steered clear of works that internalize stereotypes about it. The Sing! exhibit by Mladen Stilinović serves as a noteworthy example by expressing the rejection of both artistic and political representation that caters to colonialist perspectives. Stilinović’s work allows for new interpretations when viewed alongside August Augustinčić’s Peace Monument, which is reproduced on the banknote it uses. The current zeal for global militarization makes this artwork particularly relevant at present. The sculpture was erected at the United Nations headquarters in New York City in 1954 as a symbol of the organization’s commitment to worldwide peace. While following the traditions of monumental sculpture, it challenges the patriarchal celebration of war by substituting a male warrior on horseback, who embodies violence, with a female figure holding an olive branch instead of a weapon.

BM: Bosnia and Herzegovina was perhaps the most multicultural republic of former Yugoslavia, also its geographical and industrial centre, and it suffered the most horrific war crimes in the 1990s. A lot of works at the Berliner Herbstsalon examine the issue of Yugoslavia through a Bosnian lens – what’s behind that decision?

OF: Well, I sincerely hope not the fact that I was born in Bosnia! This attempt to be funny serves as poor counter-balance to grave reality of today’s Bosnia and Herzegovina. There are two works dealing with post and pre-Dayton’s Bosnia. One of them is an ongoing project, Four Faces of Omarska, led by Milica Tomić with Amel Bešlagić, Anousheh Kehar, Dubravka Sekulić, and Philipp Sattler. It traces how the global corporation ArcelorMittal persists in practicing discriminatory measures against non-Serb workers, thereby continuing to implement wartime policies of ethnic cleansing. Furthermore, ArcelorMittal’s decision to block the construction of a memorial centre to honour the victims of the Omarska camp represents the culminating stage of ethical cleansing. Following the eviction, imprisonment, torture, and murder of individuals, it is now time to wipe the memory of their suffering. Danica Dakić’s Zenica Triology analyzes different facets of this city and tension between its pre- and post-war identity.

BM: A significant part of this year’s Berliner Herbstsalon program, as it is with your directorial oeuvre in ex-Yu countries, is dedicated to “dealing with the past” approach, regarding the war crimes of the 1990s. In her book The Past Can’t Heal Us, the academic Lea Davis critiques this approach and the concept of “moral remembrance” and “human rights memorialization” saying that they strengthen national sentiments and divisions. To move away from academic language, a big part of ex-Yugoslav youth also feels that war-crime remembrance leads to further divisions. Do you think that there is any merit to this criticism?

OF: I wonder if active erasure of the memory of war crimes is a viable option, but didn’t all former Yugoslavian societies that committed those crimes do exactly that? It is my opinion that neither individuals nor societies should leverage victimhood to exempt themselves from criticism. However, erasing the memory of victimhood is just as concerning as immortalizing the victim’s position. And as I said above in the context of the Omarska camp, the erasure of memory of a war crime represents the final chapter of crime. And as mentioned earlier regarding the Omarska camp, getting rid of the war-crime memory is the final phase of that same crime.

BM: Besides Yugoslavia, there are two more big themes of Maxim Gorki’s theatrical season – the other wars taking place in the world and the existential questions regarding this disorienting moment our civilization is in right now (your show Frankenstein can be placed in the latter category). What brings together these three themes?

OF: Recently, two wars have been claiming the title of “The First War on European Soil after WWII”. One is the conflict in Yugoslavia, which briefly lost this title when media outlets reported the war in Ukraine as the first one. But doesn’t this question, as my colleague Johannes Kirsten puts it, implies good old Euro-centrism? What about the wars in Africa? Victims of these conflicts receive unequal media attention and empathetic responses due to the fact that these conflicts don’t occur on European soil and their victims don’t fall into Judith Butler’s category of grievable life. Furthermore, Frankenstein can be interpreted as a story demonstrating the limits of human empathy. So, I would say that distribution of human empathy and what it prioritizes is what brings together these three themes.

BM: In the upcoming show Frankenstein or the Lost Paradise, you examine the issue of artificial intelligence and its subsequent effect on humanity. How do you approach this topic and how does Mary Shelley’s novel help you do that?

OF: The show’s premiere was postponed until May due to my mother’s passing. My objective was to analyse the present circumstances, where we could be observing the final moments of human dominance with the swift advancement of AI. Nietzsche had previously expressed feelings of nostalgia and cynicism regarding this matter: “In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in innumerable solar systems, there once was a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the highest and most mendacious minute of ‘world history’ — yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die. (…) One might invent such a fable and still not have illustrated sufficiently how wretched, how shadowy and flighty, how aimless and arbitrary, the human intellect appears in nature. There have been eternities when it did not exist; and when it is done for again, nothing will have happened. For this intellect has no further mission that would lead beyond human life.”

But to make performance about what comes as a next stage in intellectual development after humans, one has to address deeper question of anthropocentrism in theatrical representation. And it is interesting to notice that field of superinteligence risk faces the same problem “It is important not to anthropomorphize superintelligence when thinking about its potential impacts. Anthropomorphic frames encourage unfounded expectations about the growth trajectory of a seed AI and about the psychology, motivations, and capabilities of a mature superintelligence.” The scariest and most exiting thing about artificial intelligence is that it may move not just beyond human comprehension, but beyond human control as well. Mary Shelley envisions trans-human, intellectually and physically superior to humans, but still bound to them by need of acceptance in its radical Otherness.

BM: You have been saying that theatre needs to adopt a more innovative, radical and provocative language, both aesthetically and politically, in order to answer to challenges of our time. Yet in recent years you steadily moved to directing classical texts. Do you see this as a contradiction?

OF: Not really. Although I see theater primarily as a visual art, and the deconstruction of theatrical logocentrism remains my constant interest, I never thought that this could be achieved by simply kicking the text – classical or some other – out of the theater. Certain post-dramatic attempts to end the primacy of the text by its total elimination have paradoxically increased its presence, giving it a kind of spectral status, making it an unwanted constitutive moment of a new theatrical paradigm. When I use the classical texts in the theater, I work on either the implosion or the explosion of their already inscribed, proscribed or suppressed meanings. In my production of Euripides’ Bacchae, the text consists of only two messenger reports. Their repetition creates a wealth of new semantic (and political) constellations. Every repetition enters into semantic mine-filed sowed by the previous one. In the time of my theatrical innocence, I used to work very much with the velocity of the text, deliberately pushing it to and beyond the limits of comprehensibility. In that situation, text starts to signify through rhythms and dynamics.

Gorki – Alternative for Germany? – Maxim Gorki Theatre

BM: When you directed your first show at Maxim Gorki Theatre in 2018, Gorki – Alternative for Germany?, you presented a very ambivalent, even pessimistic-leaning stance on the institution. Maxim Gorki, a left-wing beacon and a haven for refugees and the marginalized, sure – but an institution that cannot influence political reality, let alone slow down the ascend of fascism. This was also a critique of the art of theatre as such. Since then, you have become the Co-Artistic Director at Maxim Gorki Theatre. How do you feel about the role of Maxim Gorki Theatre now?

OF: Not really funny fact – when I was making Gorki – Alternative for Germany?, many people told me that I was giving too much importance to this party and that nobody would remember it in two years. At the moment AfD is the second strongest party in Germany! In this project, I tried to use subversive affirmation as an artistic strategy. The idea was to convince all the actors – preferably all the employees of Gorki – to become members of the AfD. It would be a very complex situation in terms of political and artistic representation and the question of where one stops and the other continues. This performance pointed also to paradox of democracy – that it can give its credential to a political platform that is utterly non-democratic or even wants to abolish democracy. In 1928, Goebbels didn’t even try to hide it: “We enter parliament in order to supply ourselves, in the arsenal of democracy, with its own weapons. If democracy is so stupid as to give us free tickets and per diems for this work, that is its own affair. To us every legal means is welcome to revolutionise the current state of affairs. […] We do not come as friends, not even as neutrals. We come as enemies!” Gorki – AfD? was not just the critique of rising xenophobic, fascisto-philic party, but of the representational model Gorki was implementing till that moment as well. I believe that this work was the most complex, yet highly misunderstood and underestimated, project that I have undertaken at this institution. The essence of my job – as a theatrical or co-artistic director – is to be critical. Or in the words of Brecht: ”Don’t start from the good old things but the bad new ones.”

BM: Following the previous question, what is your motivation for continuing to work in theatre?

OF: At times, theater has given me the sincere yet misguided promise that we can collaboratively create social change. Despite the fact that it has let me down on multiple occasions and our current relationship is, as Facebook would describe it, complicated, theater has provided me with costly lenses to view reality. Truth be told, once I remove them, I often stumble, sometimes on my own self.

Main image: Ute Langkafel

For more information, visit: gorki.de

Further reading: interview with Oliver Frljić: “Theatre is what happens in the heads of the audience”

Borisav Matić is a critic and dramaturg from Serbia. He is the Regional Managing Editor at The Theatre Times. He regularly writes about theatre for a range of publications and media.

He’s a member of the feminist collective Rebel Readers with whom he co-edits Bookvica, their platform for literary criticism, and produces literary shows and podcasts. He occasionally works as a dramaturg or a scriptwriter for theatre, TV, radio and other media. He's the administrator of IDEA - the International Drama/Theatre and Education Association.