Nihad Kreševljaković, artistic director of Mess Festival, talks to Nick Awde about the Sarajevo War Theatre, the power of memory, and the role of the artist in times of conflict.

One of theatre’s superpowers is its ability to take on different roles in different nations, adapting to the strictures or freedoms of the society and culture in which it finds itself. To make this work, theatre often co-opts other art forms – and so, in country with a complicated and traumatic history like Bosnia and Herzegovina, it wouldn’t be unusual to find an artistic director like Nihad Kreševljaković multi-tasking as a writer, documentarian and activist against the backdrop of Sarajevo.

“All these descriptions are part of what I do. Sometimes I feel more a theatre producer, sometimes more a documentarian,” admits Kreševljaković, who is artistic director of Bosnia’s MESS Festival. “But I’m not a fan of the word activist, I prefer to say that I try to act as an intellectual – although somehow it has almost become a pejorative word today. The obligation of every intellectual is to be an activist, it’s that basic idea of being a person interested in the world that surrounds you.”

Theatre is a live interaction that requires a live audience – generally face to face – meaning that it has an instant impact on audiences that other mediums such as video do not have. But how then do you identify and fix that impact for those who weren’t there?

“I have a very precise answer to that question which is based on very real experience from the siege of Sarajevo, 1992-96,” says Kreševljaković. He was an 18-year-old living in the city – his father Muhamed was the mayor – when it was surrounded and its people exposed to deadly shelling on a daily basis in what became the longest siege of a capital in modern history.

“The borders of my universe were the horizons of the city. After four years, we couldn’t even imagine that something existed beyond those hills. But we still went to the theatre, and the moment we entered, we had the freedom to travel freely in the world. We experienced the real power not just of theatre but of art.

“Of course people will tell you how art and culture are important, even the politicians, but the first cut in the budget is always art and culture. However it’s good that they believe in the lie, it’s good that we live in a world where at least we feel that art or culture could have importance. I guess those who lived through that time in Sarajevo are rare people, because unfortunately you need to be in a war to have the experience to know how deep that importance is.”

During the war there were four public theatres in Sarajevo – they still exist today –which in the years leading up to the war turned out ten productions or so annually, but during the four years of the siege they produced 57 premieres. Along with the work of independent groups, there were more than 100 premieres in total.

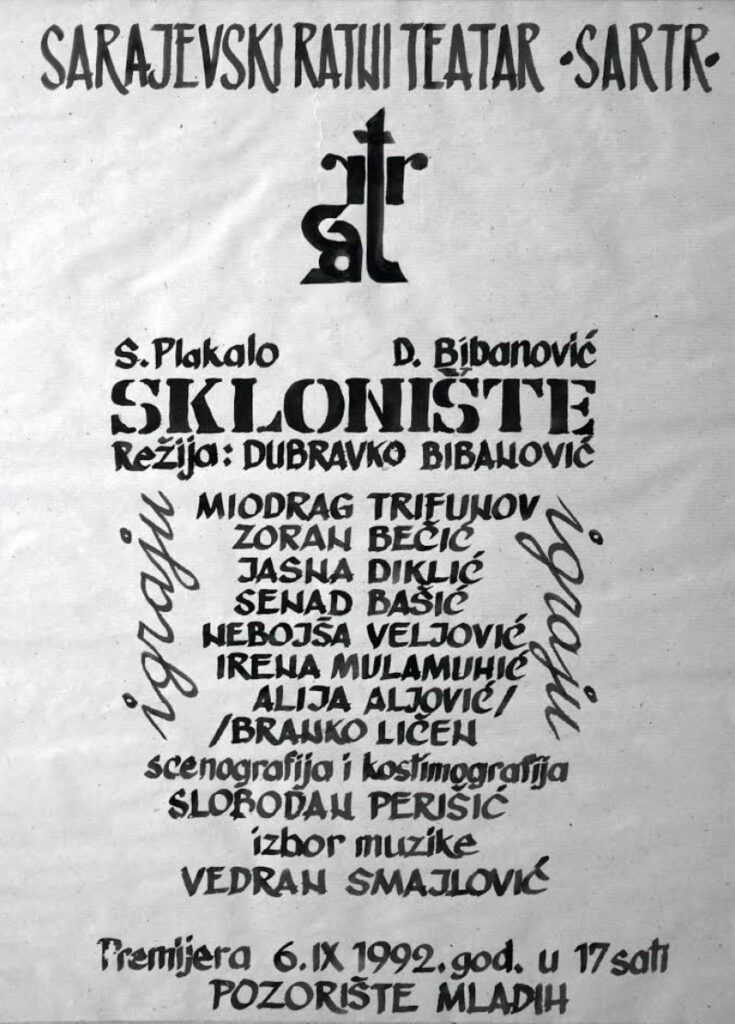

Kreševljaković works with Hana Bajrović, who has written in detail about the period, and she shows how the plays stopped using traditional patriotic texts but turned to writers like Sartre, Camus, Beckett, Shakespeare, Mrożek and Ionescu. New works too began to appear, such as Sklonište (The Shelter), the first play produced by SARTR – the Sarajevo War Theatre – which was founded on May 1992 by Dubravko Bibanović, Gradimir Goje, Đorđe Mačkić and Safet Plakalo (Kreševljaković later became artistic director from 2011-2016) during the worst months of the shelling.

Written by Plakalo and Bibanović, Sklonište premiered in September 1992 and featured actors Jasna Diklić, Zoran Bečić, Miodrag Trifunov, Senad Bašić, Nebojša Veljović, Branko Ličen, Irena Mulamuhić, Alija Aljović and Nisveta Omerbašić – and it had a remarkable run of 97 shows during the siege. SARTR then became the first Bosnian theatre to leave the country during the war when it played the 1994 Avignon Festival.

“If we came from France or the UK or any fashionable country, every student of the cultural institutions, and not just theatre, would know the names of all the people who did that first show,” says Kreševljaković. “Unfortunately we come from a small country where, instead, the rest of the world just watched our civilians being massacred.

“If we came from France or the UK or any fashionable country, every student of the cultural institutions, and not just theatre, would know the names of all the people who did that first show,” says Kreševljaković. “Unfortunately we come from a small country where, instead, the rest of the world just watched our civilians being massacred.

“In my own work, I believe that the point of art is to establish interaction, the link between those who produce a performance and those in the audience who receive it. Theatre at that time in Sarajevo took on such a pure form where you didn’t know which was weirder, the actors on stage or us in the audience – you could feel the emotions joining us. I may have seen better performances but I have never experienced such a strong connection between a piece of art and audience.

“So the audience became an important phenomenon withing theatre during the siege because all the performances were full of people. It was clear that each time you went to the theatre or cinema or an exhibition, you were taking the risk of being killed on the street, but you took that risk because you believed you were doing something worthwhile.”

Kreševljaković studied history at university and this helps him to understand the importance of keeping this sort of collective experience in the present through empirical proof. Luckily there is a lot of activity in Bosnia and Herzegovina of people researching and documenting the period. Contributing to this proof is Modul Memorije – the Memory Module, a project started during the siege and which is still running today as part of MESS.

“When we were talking about the idea of the project in 1995, we felt that the war could be over,” says Kreševljaković, “and so we were interested in how we could put forward questions like how is it possible that we have such an incredible technological revolution while at the same time such a barbarian destruction. We wanted to explore through artistic expression the relationship between science and art, between ethics and aesthetics.”

In 1996, for the first project that Modul Memorije organised after the war, they invited experts such as Claude Lanzmann, who made one of the defining films on the Holocaust, the nine and a half-hour-long Shoah, and Joan Ringelheim, director of oral history at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, and posed the question: we have this experience, how can we make it useful to everyone else?

“That was how I found my personal mission – not just to memorise things but to use memory to make us better personally and as a society,” says Kreševljaković. “The aim of my work is never to become the perpetrator, because as a historian I understand how the Serbs in the Second World War were the victims of genocide and then, just 40 years later, they become the perpetrators – but they didn’t take revenge against those who had committed similar crimes against them.

“There is the risk in any society that in a single moment we can become so frustrated that we become what our perpetrators were. So with the Memory Module, with MESS, with everything we do, our mission is to protect us from from becoming that.”

The essential story of theatre and art under the siege therefore is the human desire of artist and audience to remain human and empathetic. “I remember how frustrated I was by the fact that I lived in a world, especially Europe, that didn’t care about the fact that there was a genocide in their neighbourhood. That there were women being raped, that there were children being killed. I don’t care how they explain now why they didn’t do anything, but it’s not normal not to act.

“Unfortunately throughout history there have always been wars, just as there are today, but I have promised to myself there will not be a war in which I do not know which side I support. This is the story of responsibility – of course it’s difficult, sometimes you have to support the bad guys because they are still better than the other guys.”

Susan Sontag chose her side when she staged Waiting for Godot in 1993 at MESS and it was seen as a huge vote of confidence – in fact the square on which the Sarajevo National Theatre stands is named in her honour. Sontag called the production ‘an act of conscience’ and stressed the idea of responsibility, how artists need to come up with a response.

“This responsibility means that sometimes we need to make steps into the future that don’t make us seen as cool. We live in a world where we want to be loved by everyone and to be nice to everyone, but the reality of our world isn’t like that. If you don’t stop one crazy guy, you will have a bigger crazy guy, then you’ll have a bigger one, and in the end you have a president of a powerful country who threatens the whole world.”

The Sarajevo War Theatre

Kreševljaković wants Bosnia and Herzegovina’s memory to make people stop and listen and be a positive force for all, because “our experience is that we saw the light at the end of the tunnel”. His work on memory in theatre and other areas of documentary has led to the conclusion that the biggest deficit everywhere today is a lack of communication. “We have lost the capacity to listen to each other and to be focused on what people are actually saying, because we would rather live in a black and white world where everyone has stereotypical opinions.”

In 1997 Kreševljaković was part of the group that rebooted MESS as an international theatre festival. The artistic director at the time was Dino Mustafić – now artistic director of the Sarajevo National Theatre – who said that the festival needed to invite theatre companies from Serbia and Croatia. “At that time it was a huge statement – today it’s very normal thing. Today we communicate, we exchange, we work together. But in 1997, no. So it was the theatre people and the cultural community who were the first to establish communication.”

Kreševljaković later took over running MESS, and the festival has continued to develop this line of communication, even if it is not always what people want to see or hear. While the festival’s programming showcases the latest trends in contemporary performance, “sometimes there are people who come to the shows and they tell me that it’s always a bit heavy or brutal for them”.

“Theatre is a reflection. You can put on beautiful theatre, but the fact is that artists have to respond to world that they see – and right now everything’s looking dark. The capacity of art to change our perceptions is like the role of politicians – we pay them to work on making our lives better. Of course they don’t do that. In theatre we do.”

For further info, visit: Mess.ba

Further reading: interview with Haris Pašović: “Europe today is a Europe of inequality”

Nick Awde is a journalist, playwright, editor, critic and producer. Based in the UK, he is co-director of Morecambe's Alhambra Theatre. Books include Equal Stages (diversity and inclusion in theatre), Mellotron, Women In Islam, and translations of plays by other writers. Much of his work focuses on ethnoconflict and language/cultural genocide.