Croatian playwright and dramaturg Ivor Martinić is one of the most prominent theatre artists in the region. His plays include A Play about Mirjana and those around her and his work is full of subtle beauty and humour, always accompanied by a tint of melancholy. He talks to Ana Fazekaš about his search for artistic autonomy, and how collaboration is one of the founding principles of his work.

Ana Fazekaš: You’ve been living and working in Barcelona for the past few years. What have you been working on there?

Ivor Martinić: My latest project, Drama Feliz de un joven del país más violento del mundo just had its Madrid premiere on 17th February. This is the fourth play produced by my own independent artistic organization T25 (after Bilo bi šteta da biljke krepaju in Zagreb and Spain, and Drama o Mirjani i ovima oko nje in Zagreb), and we’ve developed it in collaboration with Planta Uno civil centre, devoted to refugee issues.

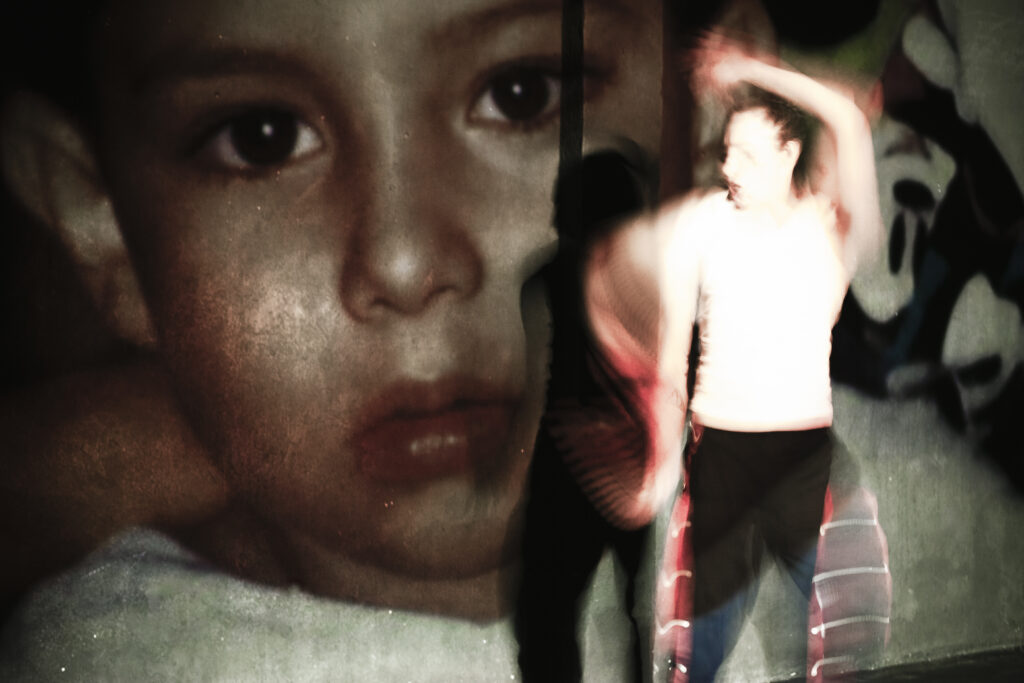

Drama Feliz is based on the life of Guillermo Miranda, a young man who moved here from El Salvador four years ago under a protection program, after enduring various forms of abuse in his home country. I met Guillermo while working with him on the Spanish instalment of Biljke, and grew an interest for his story. I’ve learned that El Salvador is among the most dangerous countries in the world with the highest rates of violence, while also being the happiest country in the world, according to some surveys. That unlikely dichotomy became the starting point for Drama Feliz.

In trying to narrate a story containing a lot of trauma, we focused on the joyful moments of Guillermo’s life; I asked him to choose photos that made him happy and they became the basis for the dramaturgy. And each time we approach a moment of trauma in the narrative, we pause… That way I think the audience can tell there is something there, but we don’t talk about it.

He’s not academically trained as an actor, but he’s a born storyteller, and right now I’m very interested in developing projects that can open up the theatre to non-professional performers. And I’m right there on stage with him, asking questions, steering his storytelling in real time. It was challenging for me to be working on a piece based so much on improvisations, for the first time in Spanish, but it was also exciting to be present as a writer in the performance, keeping the structure radically open. In one hour-long performance, we can use around 10 out of 66 photographs, and sometimes he feels confident telling some stories, while other times I feel he deflects, so every time choices are made, and a different performance is realized.

Drama Feliz. Photo: Gabriel Vorbon

AF: I find this co-existence of extreme violence and extreme happiness in the same space really interesting, have you figured out some kind of working theory about this phenomenon?

IM: We’ve tried to find some kind of theoretical explanation, but we haven’t found anything. I believe it’s a question of mentality; Guillermo, his family and friends, just seem to have a relaxed attitude towards life, maybe because they just had to learn how to live with a lot of painful experiences, and still find joy. They have developed coping mechanisms that block out the bad things.

For example, we show pictures of Guillermo’s family in the play, but his abusive father is cut out of them. And when I look at these photos, all I can see is that gaping space, and it’s gut-wrenching. But not for him – he focuses on everything else, and the hole is just a part of life! It seems people from El Salvador have a way to tailor their realities to make them more bearable, and keep their eyes on what matters most to them.

AF: I feel like that is the complete opposite of our mentality, we seem to have a reverse pathology to focus on the traumatic. Tell me more about the choice not to represent violence on stage.

IM: Well there was also this moment, when I started to get interested in his story, and Guillermo’s mother told him not to talk about everything that had happened to them because people wouldn’t understand and they’d judge. And I actually realized she was right; even with the best of intentions, looking from the outside in, we judge. And that’s not how we wanted people to engage with his story, so we invited him to tell it the way he wanted to, instead of providing an exhaustive reconstruction of his biography. Then you’re able to experience his life through his eyes.

There are sad moments in the play, such as when he recounts the story of his grandmother, who had been abused by men her whole life. But having the chance to talk about her and make an homage for his grandmother, no matter how traumatic the events, also brings Guillermo joy.

AF: And how tied is this project to Guillermo? Could it be performed in some variation elsewhere?

IM: I think so! It wouldn’t be as authentic, but we are actually thinking about translating the text to see how it could work in another context because the way he tells the story is interesting in the literary sense, and the story itself could definitely be staged in various ways. But right now I’m not sure how it will work, and which dimensions it would activate. By narrating his story, he develops a dramatic, scenic character that you can put on stage in a completely traditional way as well.

When working on these types of projects, I always try to close them textually after they are performed, and each time I get a radically different text than the one you would have seen on stage. I think of the initial performances as zero versions of the play, and the text is never a transcript. When I was working on Biljke with Maja (Posavec) and Pavle (Vrkljan), the text had gone in a different direction from the improvisations that made their way into the performance.

AF: And what about your own presence on stage in both Biljke and Drama Feliz, how is that transferred to the page or other stagings?

IM: In the text for Biljke, the Author is present in the stage directions, and the whole thing is written as a journal entry conversation about what had happened between the couple that’s breaking up. When the play is done without me, and it has been done without me several times, either that part is ignored, or someone reads it the same way a lot of my stage directions have been performed on stage, even in more traditional texts. For example, the Spanish and Argentinian versions of Moj sin samo malo sporije hoda developed a character of the narrator, explaining the story on stage.

It’s interesting that most of the audience doesn’t really focus on my part even when I am present, I guess you have to know how plays are made to be interested in this layer, and most people just pay attention to the story and the actors. But that is something that’s important to me and my work right now, to be present in the plays I produce.

I also appear in Drama o Mirjani, but through a telephone call. And I always introduce myself, ask the actors how the performance is going, and only then I read the part of Simon. Maybe at some point I’ll exhaust this practice, but right now I’m still interested in being present in various ways, as someone who doesn’t have an actor’s education, diction, or body, providing a V-effect as a different kind of presence.

AF: Do you enjoy being on stage?

IM: I think that this is a transitional phase between me as a writer, and me as a director – or rather author of the performance; I wanted to understand the mechanism of a theatrical production. I had never wanted to be the dramaturg of my own texts or to be present on rehearsals. But then when I moved to Spain a couple of years ago, I wanted to make a drastic shift, not only to stop running away from the process, but to put myself on stage. I think a lot of it had to do with a feeling of insecurity about losing my language as I moved to a foreign country, and wanting to stay connected to the language as it was spoken in the performance.

And I don’t know if I can say I enjoy it, it’s weird! I invest a lot of discipline and concentration not to get emotionally engaged with the actors’ performances, to keep the distance necessary for my position to make sense the way I intended. As a writer, I tend not to think about the audience, I don’t want to entertain them, indulge them, it’s important I follow my own instincts and aesthetics. But once you’re on stage, you want the audience to like you, to enjoy your work, it’s inevitable!

Drama o Mirjani i ovima oko nje. Photo: Luka Dubroja

AF: A lot of your practice are your own productions; how accessible, and how sustainable, is it to have your own company and work on your own material independently?

IM: I don’t really know how sustainable it is, mainly because of logistics, starting from the budget on the independent scene. It demands a lot of everyone involved, and without some kind of collaboration with an institution, it is completely impossible. And the media is lazy, hardly anyone covers anything that happens beyond the institutional theatre scene, which fails to bring visibility and audiences to independent productions. I can’t say I’ve been unhappy with how my texts have been staged and presented, I feel that I’ve had several plays that can be considered relevant: Moj sin samo malo sporije hoda directed by Janusz Kica in ZKM, Drama o Mirjani i ovima oko nje by Iva Milošević in JDP, and Dobro je dok umiremo po redu by Aleksandar Švabić.

But then, a lot of how I am perceived as an author will depend on who stages my texts, and how, so it also has to be part of my practice to decide whom I want to give my texts to, and whom I don’t. And still, you have little power over how your text will be put on stage. So maybe the need to show my own vision of the texts stems from that. But it is still important to me to grow as a playwright, and the two things co-exist, but remain somewhat separate.

I think that dramaturgs are the most underestimated part of the theatre machinery; I remember the moment when I had to pitch the concept for Drama o Mirjani, I came in completely prepared to elaborate every aspect of the work, because that’s what you’re used to as a dramaturg – for everyone to question everything you say, to have to defend everything to everyone. But when you come from a position of a director, you just have to say what you want, and that’s it. It’s actually very liberating, and makes life much easier. (laughs)

AF: But so you’ve been in a position when you’d refused someone asking to do your text? What were the deal-breakers?

Well yes. Half of your career as a playwright depends on who stages your work, and I feel that some of my best decisions were not only who I gave the texts to, but whom I refused. I’m just sensitive and I feel a certain responsibility to not give my texts to directors that I can’t connect with, that I don’t want to give entry into my intimate worlds. And sometimes you hope for the best, and it doesn’t work out, and then no one really profits; the actors agonize over the text, the director cuts the parts he or she doesn’t understand, you get a kind of censorship. But yes, there are theatres, directors, and ensembles that I just wouldn’t want staging my work, with all due respect. Fortunately, those people rarely ask. (laughs)

AF: What else do you have going on?

IM: I have a lot of interests actually inside T25, and I’d like to divide the company into several disciplines, in which we would engage with other artistic modes and media, inspired by our work in the theatre. We’ve just established M25, the music side of the company with Maja Posavec, my long-time collaborator, who has worked on two of my plays and has done the music for both of them. Inspired by the plays we work on, she will develop original music, and we’ll put it out on various platforms.

We’ve just come out with the first song, I Said, based on Guillermo’s text from Drama Feliz. The song also became part of the performance, which wasn’t initially planned. The idea is to give autonomy to various aspects of the theatre that don’t get as much visibility, so we have p25 for photography, and Studio T25 for video art with a Vimeo channel. All of the projects are based in theatre, but they expand into other media. And maybe in the end it will come down to one or two songs or a couple of photographs a year, it’s not really important, I just want to think of theatre projects as a kind of community in which various people work together creatively and inspire each other.

I’ve developed a movie adaptation of Drama o Mirjani with Zrinko Ogresta that came out recently, and now I’m working on a new film with Antoneta Alamat Kusijanović. There isn’t ever enough hours in the day for everything that I’m interested in, but I always think, if I were to win some kind of jackpot, and be able to do whatever I want, I’d still choose theatre. Although I might be crazy doing theatre at the height of TV’s golden age, and opening a theatre company in the midst of a pandemic! (laughs) I don’t know – but this is what I want to do.

Further reading: What a Way to Make a Living: The rise of feminist dramturgy in the Western Balkans

Ana Fazekaš (Zagreb, 1990) is a critic, editor, and essayist in the fields of performing arts, literature, and pop culture, currently working as freelance writer for various publications including Kulturpunkt.hr, Kazalište, Kretanja/Movements, Kritika HDP, and Booksa. She holds an MA in Comparative Literature and Russian Language and Literature, and is currently working on her PhD thesis on the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences in Zagreb, focused on psychoanalysis, gender studies and transdisciplinary art theory.