Theatre director and activist Andrej Nosov is the co-founder of cultural organisation Heartefact Fund. He talks to Nick Awde about cultural co-operation, political loneliness and the continuity of memory.

I don’t know about you, but theatre as activism for me conjures images of a hallowed tradition where artists take it to the streets, do it for the masses, stick it to the Establishment – spark revolution even. But there’s also sustained activist theatre, which coexists with the Establishment, which isn’t as commonly encountered since it demands a range of extra skills – and a modicum of nerve.

Someone who has both skills and nerve is director Andrej Nosov. “It all goes back to that moment when we decided to found the Heartefact Fund in 2009,” he says. “That was when we started this whole line – as people from the international community would put it – of using art for regional cooperation dialogue.”

Heartefact describes itself as a multi-disciplinary organisation that “strengthens critical awareness and builds an open and free society”. In between the calls on its web roster for proposals for Culture for Democracy projects and research on Kosovo-Serbia, you’ll also find thoughtful offerings such as podcasts – there’s an excellent recent conversation between Biljana Srbljanović and Doruntina Basha – and of course a string of plays new and old.

Nosov is well qualified to juggle these different levels in the name of art and, already moving with the times, it was as a young journalist that he made his mark on the NGO democracy movement. “When I started, I was an activist at Youth Initiative for Human Rights which I founded when I was very young,” he says. “We were working on dealing with the past, the crimes, atrocities and genocide, from the perspective of the youth, because we believed – and still do – that each new generation has to take responsibility into their hands.

“If we say, for example, ‘we were born in 2000 so how can we be responsible for those crimes?’ – what happens then to the criminals, what happens to the truth, what happens to memory? And how do you deal with your own identity in terms of that past, which won’t stop existing?”

Theatre can play a key role in keeping this political continuity alive by challenging post-Communist complacency – and it has regularly come under attack for doing this. Finding ways to preserve society’s memory, however, is a challenge, particularly as most young people from Serbia really do see things such as Kosovo or even Yugoslavia as mythologies already distant in time.

But it’s a perfectly understandable position to find yourself in, as Nosov points out: “My own generation lived through all this in a way – not like our parents, but we did. But for the young people now, it’s like me speaking about the Second World War.

“It is therefore difficult for us to speak about political continuity from the perspective of the voters or the citizens, because we don’t have the same citizens that we used to have, for example, in socialist times. You can say that this is a logical part of the system changing, that this is democracy, because today there is no state to tell you what to think or what to believe in.”

Nosov’s response after two decades of directing is to use ‘political loneliness’ as part of his ideology, which enables him to question all political narratives via the stage.

“Theatre fits this political space very well, and I have to say that the more time I spend in this space, the more I recognise that political loneliness is a key question for the majority of the protagonists who we know from the history of theatre.”

Theatre is a unique space because it offers an alternative voice in today’s sea of multimedia, giving audiences the opportunity to come together and witness their faults or mistakes through seeing other people performing scenes that are about those mistakes.

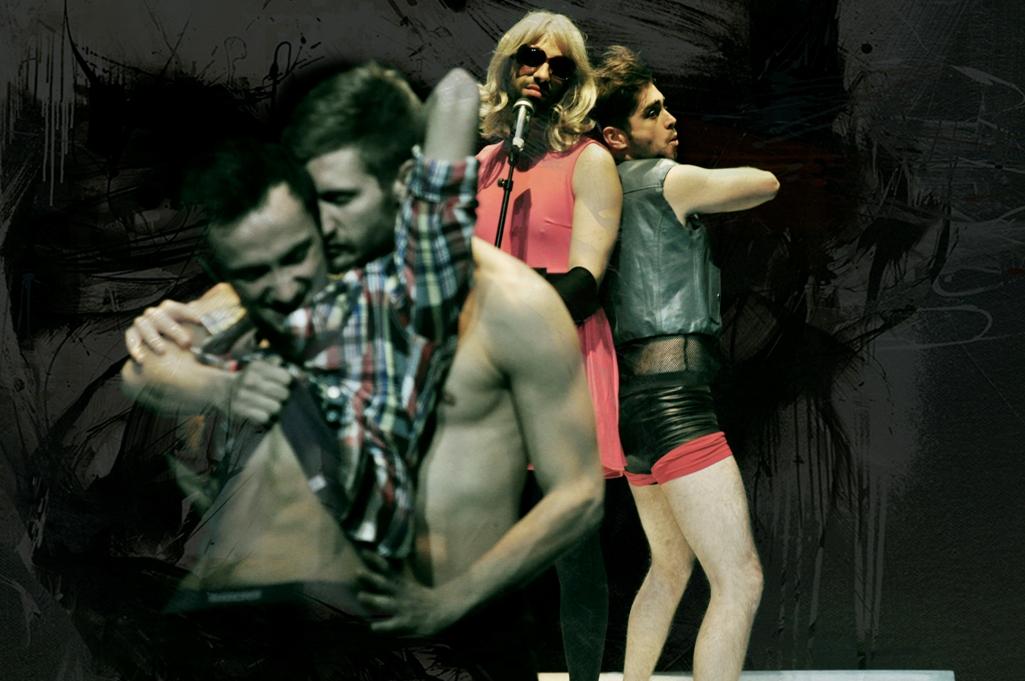

Bent, directed by Andrej Nosov

“We see beautiful faces and situations every day on TV shows, in fashion, on social media,” says Nosov. “But to actually see people with faults or who make mistakes from their perspective, people on the other side who struggle with their lives, struggle with guilt and honour, I believe you can only see that in theatre and only connect to it there. Of course it depends on what the directors and artistic editors put in the theatres and then what audiences actually choose to see. But that’s a whole other question!”

The first play Nosov directed was Martin Sherman’s Bent, chosen because, as a gay man, he believed his debut should reveal something about himself personally. When it came to assembling the cast, he naturally asked the actors he knew from around him, who turned out to be from all over the Balkans.

“So it was kind of a regional crew that created this natural space for me to work on my first play,” says Nosov. “But then I remember at the press conference discovering that it’s actually a thing if you have actors from outside of even Belgrade in your cast. I hadn’t understood this before, so that was the moment when I realised, ‘oh my God, we’re doing something political!’

“Of course I was aware of all of the perspectives that exist in general society, but I didn’t know that it’s also a huge thing in theatre. So the discovery for me was that the theatre world is no different from society. You expect this ideal of theatre as a space from which you can ask questions and challenge and all that, but in reality theatre has a very narrow and mirrored perspective of society. In a way that’s good because it means that theatre allows you to portray things that happen in all of society.”

Since Bent, Nosov has gone on to produce a line of productions, using Heartefact as a laboratory to develop these ideas of political loneliness and confronting audiences to test the continuity of memory. One relevant play is a longstanding project about Srebrenica which has proved a challenge for the director from the outset.

Acknowledging Srebrenica is one way to make a connection with the genocide, and Nosov’s connections include putting up billboards in 2005 around Belgrade to get people to see and remember the ten-year anniversary. And yet he held back from doing this in theatre, questioning why he should take the obvious political route of getting up on stage and telling people that Srebrenica happened, that they should accept it.

“I’m not saying this isn’t needed, but it’s not my thing,” says Nosov. “However 2016 made me start thinking that I really have to tell the story, although it took Corona to help me understand how to do it. So we’re working on the play now and maybe we’ll premiere at the end of this year or the beginning of 2024.

“The idea is to use theatre as a space to imagine how something bad didn’t happen, so here it’s a family that didn’t die in the genocide. We have developed the whole structure of what happened to them in the 35 years since 1995 up to now – where they live, what they are doing now. This way we arrive at a point where people can see who we are missing in this world, so they can connect with the people who should be here.”

It’s back to thinking about the audience. While many theatremakers factor in the audience only in terms of profit and who will want to buy a ticket, for Nosov it has to be a question of responding to the audience’s needs first – after all, he himself is also a part of the audience for the simple fact that he also goes to shows.

Another example is Heartefact’s production of Gishti/Prst/The Finger, Doruntina Basha‘s 2011 two-hander about a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law waiting for their son/husband to return back from the war ten years on. It was inspired by families who found their relatives in the mass graves in Batajnica, a suburb of Belgrade.

“For us it’s important to stage this play because it’s our answer to the fact that we should always remember that people are still waiting for the facts and the truth about what happened just ten kilometres from Belgrade. Of course you can say, yes but in the end who’s going to understand that this actually happened right here in Batajnica because this is being told in a play?”

But that’s precisely the risk of theatre, he points out. If people can connect to these two women and what has happened to them, then they may read the programme and find out more, and so they’ll remember. If they don’t connect, something still might click when they see, hear or read something at some point later. “It’s how to leave a mark on the other person, something that they leave with,” says Nosov.

A big step in understanding this relationship with the audience came when Nosov put on a production at the National Theatre. This was 2022, the year of EuroPride in Belgrade, when everybody expected Nosov to respond with a drama “about two gay guys fighting for a cause”.

“Instead, I saw some plays at the National where I saw people reacting in the audience who were not reacting as I did, and that got me thinking about what they were laughing at, what they were joking about. I decided that I needed to do a play about people who don’t see things the way I do, I needed to understand them, to find out what is so funny there for them. Not in a bad way, but let’s just see.”

At the same time his producer Beo Art was proposing a co-production with the National – and a book came to light as the perfect choice, The Temptation to Be Happy (La tentazione di essere felici), by the Italian writer Lorenzo Marone. Retitled Sitnice koje život znače, the story follows a grumpy old man who tries to reconnect with his family and discovers not only that his son is gay and is living with another man but has been afraid for 40 years to tell his father. Dramatised by Đorđe Kosić, the National greenlit the production and it sold out.

Sitnice koje život znače, Narodni Pozoriste Beograd

“People adored it – and all those people I’d been watching in the audience bought tickets to sit in the expensive seats,” says Nosov. “You shouldn’t always say yourself that you were smart in making a choice, but it was a good strategy because I understood something about the people in this society who would have different opinions in that context. I didn’t attack them, I just gave them space to reflect on their own position.”

It’s important to work on making minorities seen and present in the public eye, but if at the same time we don’t shed light on the silent majority who feel threatened by those minorities, then we create gaps for hidden conflict which will appear 20 years later when we don’t expect it. We’ve seen this happen with the Former Yugoslavia, and we’re seeing it happen now with the right wing coming to power across Europe.

“It’s the same for the audience,” says Nosov. “We cannot pretend that it isn’t hard to put people from Kosovo and Serbia on the same stage. Luckily we’re not killing each other any more, but Serbs and Albanians, Kosovo and Serbia, Prishtina and Belgrade – however you want to put it – we are still in conflict.”

The key question then is not simply how Serbian theatre is addressing this impasse but how Kosovo theatre is working on a positive way forward too. It has to work both ways. Theatremakers can say anything they like on stage but, if we’re honest, there isn’t much that is said on stage that can’t be said with similar effect in an Instagram post. For theatre to be good, effective, influential, its makers need to do more to understand and meet the needs of audiences.

“We have to be aware that our audience is not looking for answers from us, they’re not looking for guidance from us. But we sometimes think that if we go on the stage and say things, then it’s enough. It’s not, it’s just covering our asses. When you come into the room you need to want to know who is in the room, who you’re addressing. Otherwise, you should write books.”

For more information, visit: Heartefact.org

Further reading: Interview with Doruntina Basha: “There is a knife in all of our backs”

Further reading: review of Our Son (Heartefact)

Nick Awde is a journalist, playwright, editor, critic and producer. Based in the UK, he is co-director of Morecambe's Alhambra Theatre. Books include Equal Stages (diversity and inclusion in theatre), Mellotron, Women In Islam, and translations of plays by other writers. Much of his work focuses on ethnoconflict and language/cultural genocide.