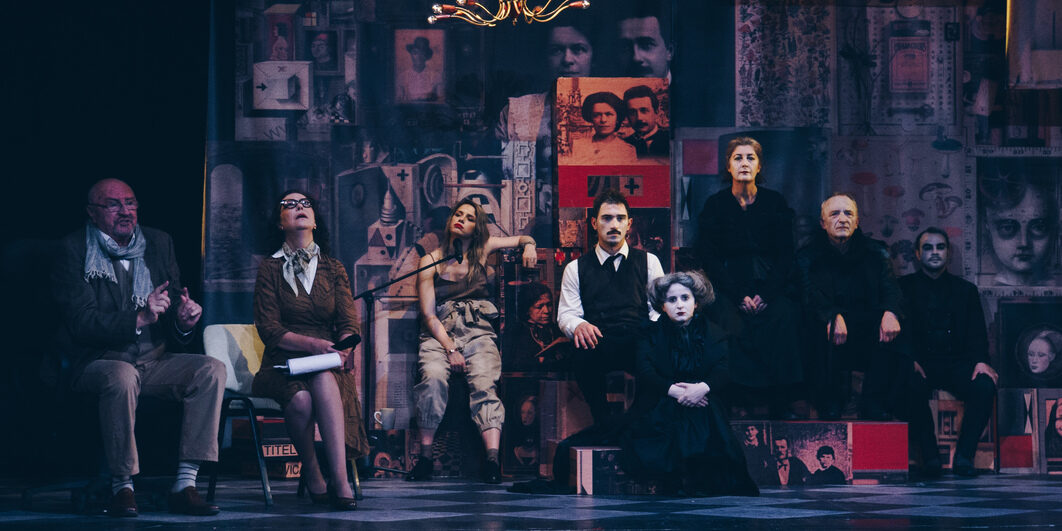

Sombor National Theatre, Sterijino pozorje and Novi Sad – European Capital of Culture; premiere May 26, 2022

The life and work of physicist and mathematician Mileva Marić Einstein remain at least partly a mystery. She was one of the few women who gained higher education at the end of the 19th century and she was the only female student at Zürich Polytechnic at the time. But despite her pioneer status, historians, scientists and the general public were uninterested in her persona for decades. She was barely known as the first wife of Albert Einstein, whom she met during her studies, and only recently has the public (mostly in Serbia) taken an interest in her.

One thing is sure, Mileva’s achievements – no matter how significant – were underappreciated and sidelined because she was a woman. But did she really help Einstein develop the General Theory of Relativity or is that just wishful thinking of some feminists and Serbian patriots? Is Mileva an example of a proto-feminist or, because of her difficult life, a female martyr who fits into the patriarchal image of a woman? Did nationalistic authorities in Serbia finally acknowledge her just for the sake of creating another national hero?

These are the questions that the performance Mileva raises, aiming to at least struggle with them if not to give satisfying answers. The producers of the performance – Sombor National Theatre, Sterijino pozorje and the foundation Novi Sad – European Capital of Culture – assured multiperspectivity on these complex questions by inviting a relatively big all-female artistic team to work on the performance. Some of the most prominent regional playwrights and dramaturgs wrote the text for the performance – Milena Bogavac, Olga Dimitrijević, Tijana Grumić, Vedrana Božinović and Vedrana Klepica. Jelena Kovačić adapted the text and Anica Tomić directed the performance.

The result of these diverse approaches is a play with an episodic structure and with different thematic and stylistic choices. But the show is not an omnibus, there are narrative links between the episodes. After the prologue, the first part of the performance is a “digest” or a run-through of Mileva’s biography. It later turns out that this part is also a performance within a performance that a group of fictional artists created. These artists, as well as several other characters like the professor of physics, the professor of history and the moderator, are part of a debate that takes place at the technical high school “Mileva Marić Einstein” in Novi Sad. This debate revolves around the question of whether Mileva influenced Einstein’s work or not. The last part of the performance is a monologue of a former student who was raped twice during her teenage years at the “Mileva Marić Einstein” school. She confronts the ghost of Mileva saying that she has little to offer to today’s girls and women except for the image of a female martyr (Mileva’s daughter died of scarlet fever, Mileva was widely discriminated against as a woman and had many financial difficulties after her divorce with Einstein).

Even though these different segments seem intriguing, there’s an underlying feeling during the whole performance – the authors struggled with the lack of material and failed to give any conclusive answers to the questions they raised. The best example is the second part of the performance, the debate where the conservative side argues that there is no conclusive proof that Mileva influenced her husband’s work and the feminists argue that she and Einstein deserve equal credit for the General Theory of Relativity. But the feminists admit that there is no proof for their claims and that they are basing their conclusions on the probability of how the historical events and Mileva’s life as a lone female scientist played out. It is obvious to an observer that the winning side of this fictional debate – contrary to the authors’ intentions – is the conservative side that simply speaks the truth that there is no proof of Mileva’s ground-breaking theoretical achievements. Even more contradictory to the feminist intentions of the show is that this fictional debate is played out in a farcical manner, so when the argument gets heated up, one of the feminists slaps the professor of history, degrading herself to a stereotype of an aggressive feminist.

Given this series of contradictions in the attempt to meaningfully interpret the scarce historical material, the final part of the show that thematizes sexual violence feels like a diversion from the main topic. This section’s story, of a high school student who’s raped twice, is so strong that it feels like it belongs to a separate performance, but it is artificially incorporated into Mileva – that results in a number of problems.

Since the story is set at a concrete school in Novi Sad that holds Mileva’s name, the question arises of whether the rape cases actually happened at the school or are they fictional – and if so, why involve a real institution where people work and study? And it seems dramaturgically implausibly and ideologically problematic that the biggest enemy of a young rape survivor is another woman, Mileva – no matter how much the patriarchal society co-opts her life-long suffering.

The most notable performance is Ana Rudakijević in the role as Minja, the former high school student and rape survivor. Her character is full of internal conflicts caused by her teenage traumas, and Minja is perhaps the only character with an arc that progresses from bitterness and judgment of Mileva’s martyr image to understanding and alliance with this historical figure (represented in the show by a video where the two characters meet).

These elements of video work (Filip Mikić) are symptomatic of the general style of the show that oscillates from realistic to dream-like. The set design (Igor Vasiljev) and the costumography (Drina Krlić) follow the same pattern, from realistic portrayals of costumes and interiors to subjective scenes filled with darkness and fog where characters present their inner monologues. But these oscillations reflect the authors’ indecision on what to do with the story at large – is the show an examination of concrete historical events or a fantasy where the character of Mileva is a projection of the authors’ intellectual obsessions? The truth is somewhere in the middle. And nowhere.

For more information on Novi Sad European Capital of Culture, visit NoviSad2022.rs

Further reading: Novi Sad European Capital of Culture theatre programme

Borisav Matić is a critic and dramaturg from Serbia. He is the Regional Managing Editor at The Theatre Times. He regularly writes about theatre for a range of publications and media.

He’s a member of the feminist collective Rebel Readers with whom he co-edits Bookvica, their platform for literary criticism, and produces literary shows and podcasts. He occasionally works as a dramaturg or a scriptwriter for theatre, TV, radio and other media. He's the administrator of IDEA - the International Drama/Theatre and Education Association.