Writer, director and filmmaker Hakan Savas Mican talks to Tom Mustroph about his Berlin trilogy, making work about the migrant experience and why it’s important to talk about questions of class.

Hakan Savas Mican is an unorthodox figure in the German theatre scene. His work explores migrant lives in Germany, and the differences between first, second and third generation immigrants. His recent work includes the Berlin trilogy Berlin Oranienplatz, Berlin Karl-Marx-Platz and Berlin Kleistpark. His plays deal with generational conflict as well as conflicts of class and what a “right life” might look like. Born in 1978 in Berlin to Turkish parents, he grew up in Turkey and in 1997 returned to Berlin as an almost-adult. He’s been a director-in-residence at the Maxim Gorki Theatre since 2013.

Tom Mustroph: You have been a writer, director and a filmmaker – how would you define yourself?

Hakan Savas Mican: When I studied film, we saw ourselves as auteurs, as the up-and-coming Ingmar Bergmans and Michelangelo Antonionis. But we realised that film as an art form is dying. I observe also how my colleagues have to fight to produce a film. They have to wait years. I am rather impatient – too impatient for such long processes. Theatre as an art form is much faster. It allows me to bring out what keeps running in my inner self.

Tom Mustroph: That is when you write your own pieces?

Hakan Savas Mican: That is my favourite approach. But I am also not so fast or prolific to write two, three pieces a year. I need time, also to be content myself with the text. And it is also an emotional process to write, and that needs time too. I doubt, to have that safe space to write each year a new piece. I would also not like to have the pressure to finish one each year. Therefore, to survive economically I am also constrained to direct others peoples’ plays. Lately I did five productions, but only for two I wrote the text. But yes, I have still in mind the idea of the auteur. I would really like to do it like Bergman. In winter, when it is cold, to write and also to do theatre, and then in the summer to shoot films.

Tom Mustroph: In your Berlin trilogy you came quite close to that ideal, at least that was my impression. The titles of plays were all Berlin places – Oranienplatz, Karl-Marx-Platz, Kleistpark. What do you like about these places?

Hakan Savas Mican, First of all they had very personal relations [to me]. I lived for almost 14 years at Oranienplatz. My parents lived at Kleistpark after they returned from Turkey to Berlin. In my first ten years in Germany I spent a lot of time there. And near Karl-Marx-Platz in Neukölln, a lot of my friends lived during my studies, therefore I was quite often there too.

Tom Mustroph: In the office where you write, the windows look out to Oranienplatz. Did you literally sit here, look at the place and put into the piece what you saw?

Hakan Savas Mican, No. The stories I wrote, I had in my mind before. The sources are interviews and also my own experiences. What I write, is inspired by true events, but they are fictionalized. The true story of the counterfeiter in Oranienplatz originally took place in another Berlin borough, in Spandau. But I thought, Oranienplatz might fit the story. The protagonist was on a journey through the very last day before he has to start his prison sentence of five years. Kleistpark is the most autobiographical of the pieces. A lot of elements of my own past appear, even a video work I did in film school. And on the documentary level, my own mother appears.

Tom Mustroph: The main characters of the trilogy all live in a situation of transit. They are trying to move away from something, from their surroundings, or their home. They are forcing themselves to a rise on the social ladder. Why did you focus so much on this aspect?

Hakan Savas Mican: The emotional world in which the [characters] are, and the questions, they raise, have a lot in common with me and my family. I am a working-class kid. I grew up in Turkey. I attended a private school there. My parents, who worked in Germany, to provide me the best possible education, had to pay a lot for this school. I was there together with sons and daughters of judges and university lecturers. They had for instance a piano at home, where the daughter of the house used to play western pieces. You could see, which possibilities they had, and which others they did not.

When I came to Germany at the age of 19, there came additionally a sense of strangeness in a new social environment. That’s why the question of class plays such a big role in my pieces. They focus on Turkish migrant workers and the effects on this situation of families and family structures. And how to break free of that? And what gets broken? That is basically the main issue of “Kleistpark”, where Adem, the academic, has almost done this journey. He left, where he came from, has almost reached the other side. But still there is something in the family’s past, what holds him back. And this comes from his mother,

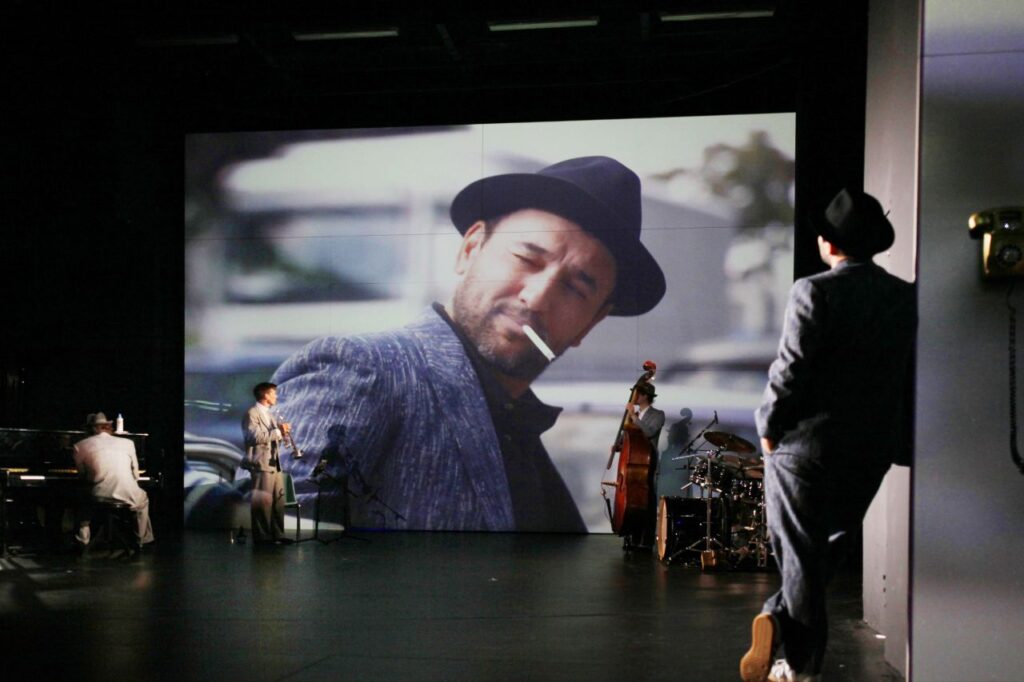

Berlin Oranienplatz at Maxim Gorki Theatre

Tom Mustroph: How distant from each other are these different generations of migrant, the first and second generation as well as the third?

Hakan Savas Mican: They are so different in their aims and demands. In my generation, of people between 40 and 50, at least in Berlin, I notice a certain prolonged adolescence. We have a lot of projects and are very smart; we leave a lot of options open. But nothing is decided yet, nothing done properly. There is also a loss of trust and self-esteem. Because if you start to do something seriously, than the risk to fail is always there. And we are, at least I think so, a very fearful generation, who wants to avoid failure and therefor hesitates to take decisive steps.

Tom Mustroph: Like moving into flat together and therefore closing the option of living in separate apartments?

Hakan Savas Mican: Yes. Even that. And in that moment {in the play] comes from his mother. She belongs to the first generation of working migrants in Germany. She lives in Turkey now, but after a lot of years she comes to visit her son. And because she knows, she has to die in the near future, she wants to put right some things from the past. She left her son, when he was very young, in Turkey, while she worked in Germany. She brings him a lot of money. And that is the catalyst, that all are confronted with the question of what kind of future they all expect. And the point arrives, where talking or finding a solution seems impossible.

Tom Mustroph: That fits the definition of a classic tragical situation.

Hakan Savas Mican: During the writing process I was thinking that these conflicts could also be valid for a young guy in Los Angeles, with a Hispanic background maybe. The question of class is so important. It is universal and continues to be relevant.

Tom Mustroph: Two of the pieces you directed recently, Uncle Wanja by Chekhov and Transit, after the novel by Anna Seghers, is, also deal with movement and migration. “Transit” covers the situation of refugees during the time of the Nazis, with characters trapped in the bureaucratic system – like refugees today – whereas Uncle Wanja deals more with inner migration, with people, who want to leave, but do not succeed in leaving.

Hakan Savas Mican, When I direct other texts I try to choose ones who correspond with my interests, with thoughts and problems I have in mind. And you are right, movement does not necessarily need to be geographic. The interesting aspect is the inner change of the protagonist. And in “Transit” I am fascinated by the characters. This man constantly asks himself, what happens with his life. He feels flung around in his life. And therefor he decides that this should at least happen in the most beautiful cities of the world. And this is one aspect, which is very modern, to be thrown inside a crazy bureaucratic machine. And for these men the core question remains, no matter what situation they are in: What kind of life is worth living, what is the right life, and what may be the first step in this direction?

Berlin Kleistpark. Photo: Ute Langkafel

Tom Mustroph: Would you like to see your own work directed by other directors?

Hakan Savas Mican: Of course, I would love it. Maybe it has not been done yet because people are afraid about the Berlin in the title. But it does not necessarily need to be Berlin. As I said before, the conflicts are more universal.

Tom Mustroph: Maybe the reason is also, that theatre directors in Germany and also Switzerland and Austria think, they have to have migrant actors for the roles. And although there was some movement recently, a driver of that is Ballhaus Naunynstraße and Gorki theatre in Berlin, where you also work, still a lot of ensembles are mainly white and German.

Hakan Savas Mican: At first I want to say that, for me, it is not necessary that only an actor with a migrant background can play these roles. Actors are actors, and their profession is to change, to transform themselves. But roles like these in my plays are important, because for a very long time, people with a migrant background were marginalized in the world of theatre with the observation that: there are not many migrant roles in dramatic literature, and therefor there are less possibilities to get a role. This has changed, fortunately, and Ballhaus and Gorki played a key role in this process. Though it is still not so easy for migrants to enter acting schools and universities.

Tom Mustroph: Is it also a factor, that for many migrant families, social rising is more important than for German families, and working in the theatre is not an elevator in this respect?

Hakan Savas Mican: Oh no, this has changed a lot. Turkish families go beyond the cliché of the old women with the headscarf. Those are the stereotypes, which are reproduced in the news. No, they have acquired capital, in the material sense – they own nice houses – but also in terms of education and knowledge capital. And for those families it would be fantastic if their children have the desire to do arts, to become actors or directors. They would support them! But still the German system, theatre and television, is not yet ready for that. It is a shame that almost 70 years after the first working migrants from Turkey came to Germany.

Tom Mustroph: You told me, that your family originates from the Black Sea, but then you moved to Ankara, later Istanbul, and then to Berlin. From this multifarious perspective, how does the Balkan region look to you?

Hakan Savas Mican: The Balkans are imprinted in me like a genetic code or a frequency. There are several reasons for this. Until I was 11 years old, I grew up at the shores of the Black Sea, only a few hours from the border with Georgia – to the then Soviet Union. And we very much sensed the icy air from the Cold War. Afterwards we moved to Ankara. When my parents went to Berlin, each summer we travelled back to Turkey. We packed everything, what was needed in a BMW or a Ford Granada and hit the highway. There were always two stops, one in Austria and the other one in ex-Yugoslavia. It was always working colleagues of either my mother or my father. We spent the night there, we ate and talked, and the next day we hit the road again. I felt there very at home, very familiar, with the language, the whole atmosphere.

Another reason is, my uncle Ali lived in Berlin with Elizabeth, a woman from Slovenia. He also had a family in Turkey; she knew that, and the family there knew about her. It was a very modern relationship, also for our times now, that this Turkish “Gastarbeiter” (migrant worker) lived with this woman from Slovenia. And because Elizabeth had no children, I was like a child for her, and she was a bit like a mother to me. So because of all these elements I feel, that the Balkans are a part of me, and I am part of the Balkans. Also, when I meet people from the ex-Yugoslavia, from Bulgaria, from Greece, there is no getting-to-know needed. There is a very close relationship, a mutual understanding. When I was in Tuzla, in Sarajevo, in Thessaloniki, I met so many people who had the same experiences, who were left alone by their parents, because they worked abroad. That is why I think Balkans are imprinted on me.

For more on Berlins Gorki.de

Further reading: Oliver Frljić: “Theatre is what happens in the heads of the audience.”

Tom Mustroph works in Berlin and Palermo as a freelance journalist and dramaturg. He operates in several journalistic fields, such as theatre, fine arts and sports. He is most interested in how self-responsible work can succeed elegantly and in accordance to minimal moral standards. He collaborates with several German language publications such as taz, FAZ, Neues Deutschland, NZZ, Theater der Zeit, zeit online, Deutschlandfunk and WDR.