In the latest in her series about relocating to Sweden, Duška Radosavljević Krojer discovers a link between her new hometown and the intelligence expert Stevan Dedijer.

It all started quite accidentally during our house-hunting phase in Lund when I spotted the surname Dedijer on the intercom to a 1960s apartment building in the east part of town. This very unusual and rare name sparks immediate associations with the highest echelons of the Yugoslav elite –Vladimir Dedijer had been famous as Josip Broz Tito’s personal biographer, former partisan, government official, international human rights activist, and academic.

Distracted by other matters at the time, I put this down to coincidence and forgot about it until someone brought up the Stevan Dedijer link in response to my earlier retracing of August Strindberg’s steps in Lund. Vladimir Dedijer’s older brother Stevan was, incidentally, *just* a Princeton University alumnus, nuclear physicist, journalist, military parachute, and academic, who as it is often remarked erroneously but with a degree of glee, founded the first ever university ‘spy course’ at Lund, of all places.

Stevan Dedijer’s autobiography, which I loaned from the university library over the Christmas break, reads as a sort of ‘who is who’ of the 20th century; Dedijer was never more than ‘six degrees of separation’ away from any historic or powerful personality in the world – KGB agents, the CIA, presidents, princes, scientists, generals, business people, even actors and other celebrities make it into his immediate circle of friends and acquaintances. He lived to the ripe old age of 93, so his life abounds in coincidences which play out across decades, and scenes that resemble various genres of screenplays (war battles, political underground mysteries, romantic thrillers). Dedijer’s prose, which was eventually edited for publication by his Swedish wife and son, ultimately paints the picture of a happy-go-lucky but deeply thoughtful individual, a charming womaniser blessed with the reliability of a family man, and a Bosnian Serb who loved Croatia. It is perhaps this conscious tendency to resist the stereotype – and to complicate his personal standpoint in the interest of truth-seeking – that has also obscured Stevan Dedijer from the limelight of the public spheres he moved across throughout his life (1930s America, 1950s Yugoslavia, 1960s Sweden, and 1990s Croatia).

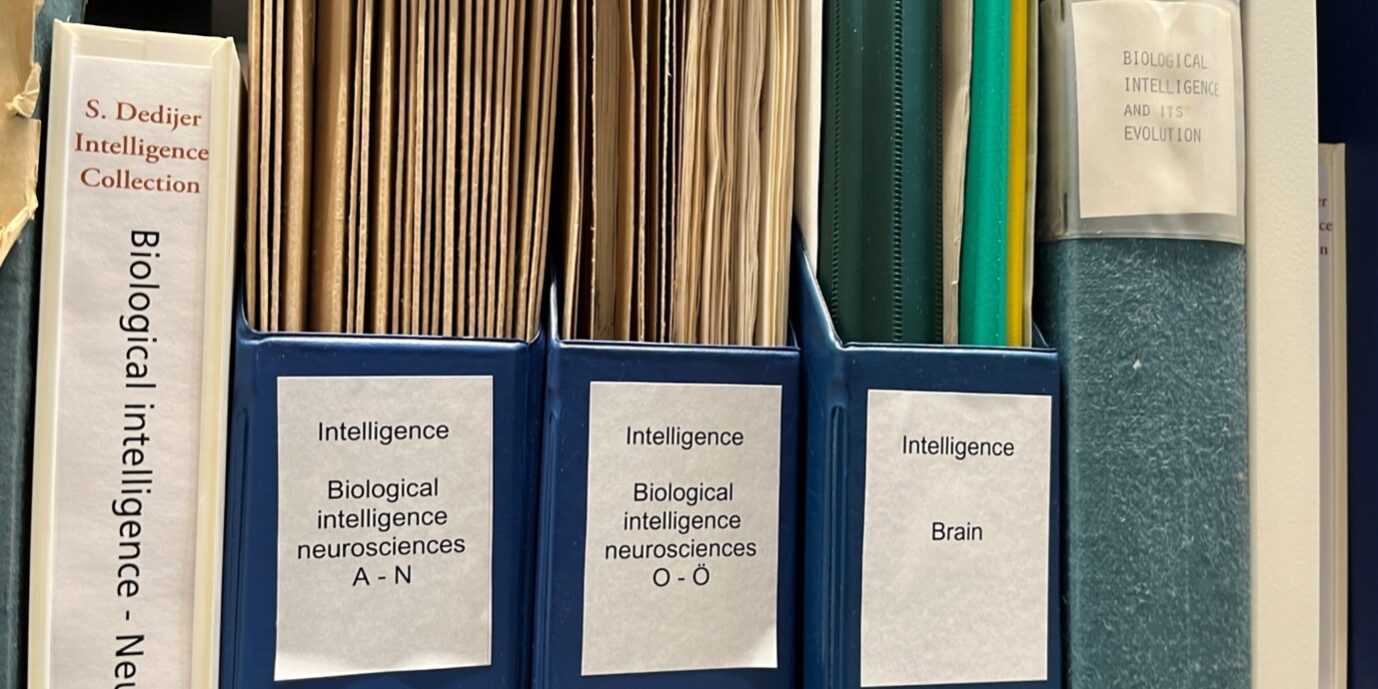

Last week I finally made it to the Stevan Dedijer collection: several rows of book shelves, newspaper articles, and handwritten notes assembled over the decades he worked at Lund University. Dedijer had ended up in Scandinavia by a lucky accident around the time of his 50th birthday. After a spell of trying to lead Tito’s nuclear bomb project in the 1950s, and disillusioned by the actual state of economic and political affairs in the then Yugoslavia, he fell out of favour with the current regime but was denied a passport to leave the country for a few years, which he spent in an internal exile. He only managed to get out at the intervention of Niels Bohr who invited him to join a research project at his institute in Copenhagen, in collaboration with Lund university. One thing led to another and Dedijer ended up creating a new area of study at Lund, concerned with Research Policy – the politics of knowledge production and intelligence management in a broadest sense. His collection, held at the School of Economics, has sections on Biography, Biology and Business, as well as Novels, Journalism, and Espionage.

Particularly interesting is Dedijer’s thematic focus on ‘Privacy’ or ‘Secrecy’, as it holds the key to his crucial intervention in the 20th century history of intelligence studies. His absolute belief in openness of access and complete transparency was indeed a radical idea in the age of secret intelligence missions, but it is now, two decades after his death, the absolute gold standard in most aspects of global research policy. It is here that Dedijer’s adopted context of Sweden might actually hold some illuminating relevance.

One thing that really shocks newcomers to this country is Sweden’s attitude to personal data. Within Sweden you can now freely access an online public database which contains up to date personal information – telephone numbers, street address, occupation, salary – pertaining to any legal Swedish resident. Though this might feel quite exposing to non-Swedes, such a level of openness of information is perceivable quite simply as an expression of trust that members of the Swedish society have traditionally had towards each other, a sort of consensus around horizontal Scandinavian collectivism that at the same time values and endorses individuality.

Having experienced a highly individualist cut-throat capitalist context of early 20th century America as well as the hierarchical collectivism of socialist Yugoslavia, it might be surmised that Dedijer eventually found a golden mean in Sweden. ‘I know that by [the] opportunities and privileges I have, I belong to the world elite’, wrote the octogenarian Dedijer in a footnote to an article he penned in 1993, ‘and I strongly believe I want everyone to have them’.

In 2000 Dedijer wrote to George Soros to lobby him to fund the creation of a ‘cyber city’ in Dubrovnik, a year-long event designed to make Dubrovnik into ‘an economically and socially prosperous intellectual city’, rather than ‘part of the “developed” Mediterranean coast, ruined by laissez faire mass tourism’. He based this proposal on two personal insights: 1. that it is harder to get rid of old ideas than to develop new ones, and 2. that bridge building between disciplines of knowledge was essential, in the sense of Edward Wilson’s idea of ‘consilience’ or interlocking of causal explanations between disciplines. Although I do not think this project succeeded in practical terms, a particularly revealing side remark is contained in another letter Dedijer wrote to a Zagreb-based collaborator in connection with this initiative, warning that the new Croatian government was in danger of repeating the ‘colour blindness’ of Tito and Tudjman by failing to understand the ‘main lever of development’: the individual and systemic creativity.

As I read this I am thinking again of the one thing which has become a running theme of my own Swedish experience – improvisation. I am thinking of the vital significance of the ability to embrace risk that accompanies openness to both change and diversity, and how this is only possible through abandoning adherence to preconceptions and through a readiness to respond spontaneously to the here and now. Within the arc of his own lifetime, Dedijer’s intellectual endeavours bridge between an exact stance of physics defined as it is by its ‘laws’, and a conclusive conviction that the main lever of development is defined by something so unruly as individual human creativity and, moreover, its workings within a collective. Surely this is a key nugget of one person’s old age wisdom, defined, surprisingly, by the very opposite of conservatism.

I am thinking this places the skills of improvisation on the level of the imperative in any possible considerations of futurity.

I have subsequently discovered that the Dedijer family tree does also extend into the world of theatre. His daughter from one of his three marriages is a celebrated Croatian costume designer, Danica Dedijer, while her son Jerko Marčić is an actor/deviser particularly renowned for his collaborations with Oliver Frljić and Bobo Jelčić.

In an interview Marčić gave in 2018 he notes that his grandfather was not overtly sympathetic to his choice of career as he perceived theatre to lack a sense of purpose. But Marčić suspects this was only a provocation given many potential parallels between his grandfather’s interest in open information flow and the processes of meaning-making in devised theatre.

And, as I look ahead to the future, I think he is right.

Read the first part of Duška Radosavljević Krojer’s Migration Diary: An Improvised Life, and the most recent instalment Close Doors

Duška Radosavljević Krojer is a writer, dramaturg and academic. She is the author of award-winning academic monograph Theatre-Making: Interplay Between Text and Performance in the 21st Century (2013) and editor of Theatre Criticism: Changing Landscapes (2016) and the Contemporary Ensemble: Interviews with Theatre-Makers (2013). Her work has been funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council in the UK multiple times including for www.auralia.space (2020-21) and The Mums and Babies Ensemble (2015). She is a regular contributor to The Stage, Exeunt and The Theatre Times.