Artists and theatre students have recently taken to the streets in Greece to protest the devaluing of their education. Nick Awde spoke to some of the organisers about what prompted them to protest and what they hope to achieve.

Energy crises, migrants, post-Covid economy, Ukraine… it’s understandable if you missed Greece’s theatre protests in your news feed. There’s so much happening. And well… students and arty people are always occupying something somewhere, aren’t they?

But in Greece something has been playing out on a very different level as theatre students have taken protest from the stages to the streets. It demands we take another look. Why? Because the students are controlling the national narrative, educating the rest of the country. Why? Because in the name of cuts and the war on culture, Greek theatre faces a generational extinction event from which it may never recover. Why? Because if theatre goes, then why not the rest of our arts and education?

The spark was in December 2022 when the government passed presidential decree 85/2022 relegating higher education performing arts qualifications to the level of high school diplomas. The students’ response was instant.

“The artistic movement spread across the whole country,” says Katerina Kaoustou, a drama student at the National Theatre of Greece Drama School in Athens. “Groups were mobilised from all the theatre schools, from the art schools and even the high schools, and it eventually took on the scale it has today.”

It was the students of the National who were the first to occupy their building, a move that was quickly taken up by students in other universities and the professional sector.

“It’s a new phenomenon because nothing like this has happened in the artistic sector for more than 20 years,” says Nikiforos Papadoudis, who studies direction at the National. “But this isn’t just about qualifications, it’s also about funding and our working rights. It’s new because the artistic movement now knows it has to be part of the whole movement in Greece trying to stop the privatisation of everything.”

The protests stepped back out of respect for the tragedy of the Tempi train crash that saw the loss of 57 lives and 80 injured in February 2023, which itself resulted in some of Greece’s largest ever protests as the nation declared its grief and anger at government mismanagement. It is against this chaotic backdrop that students are taking an increasingly leading role in the wave for change under the umbrella of the Coordinating Committee of Drama School Students.

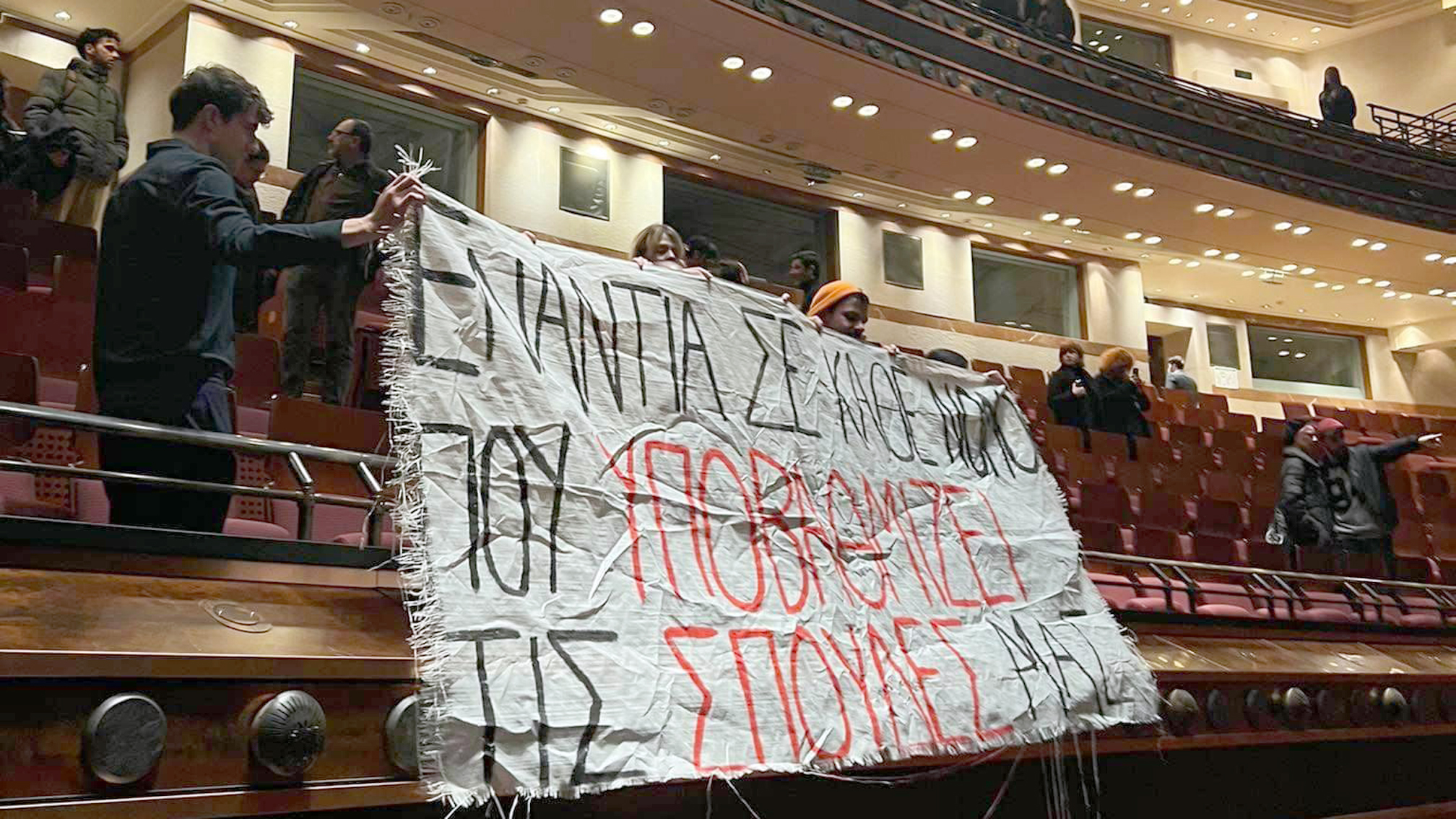

Foyer of Rex Cinema & Theatre Hall, one of the National Theatre of Greece’s venues where the Marika Kotopouli space is the largest stage in Greece – the banners say: “Occupation – Rex” and “No to the degradation of our studies” Photos by: Katerina Kaoustou

The government’s new law states that theatre school students in the public system will graduate at secondary education level, not university. This effectively seals a process that has been going on since 2003, where performing arts graduates have seen the gradual removal of recognition of their professional status, graded as a technical education qualification and thus entitled to a corresponding salary.

The occupation of the Tsiller mainstage in Athens by the National’s student union had the effect of uniting for the first time private theatre school students and arts professionals, who occupied other state theatres such as the Rex complex, also a National building. They staged a high-profile protest at Elefsina, which as Eleusis 2023 is one of this year’s three European Capitals of Culture.

The main goal is restoring accessible-to-all university level education and introducing support for housing and living, resources and staff. Disturbingly, the decree grants private colleges the same rights as public education – contrary to the Constitution which guarantees higher education as public, offered exclusively by the state and free.

After consultation, the government issued a joint ministerial decision that addressed none of the demands but in reality confirmed its wider move to privatise education and downgrade state degrees. As Kaoustou points out: “When a professional is not recognised as having status and corresponding salary in the public sector, how can they be recognised in the private sector where there exists no structure for this?”

“It was the privatisation of higher education that was the common ground which made people go to the streets,” adds Papadoudis. “In fact most people in the movement are from the private academies and private theatres, and the idea that more public funding is needed to create more public arts institutions is something new.”

A major step was the Support Art Workers movement which emerged in 2020 during Covid to create registries to get arts professionals Covid support, but today it’s clear that all university-level disciplines are under threat.

“After the tragic accident in Tempi confirmed state negligence in the worst possible way,” says Kaoustou, “society and our artistic movement have grown together and now there is a real platform for everyone’s demands – so none of us have to suffer unemployment and the privatisation of all the state institutions that are provided free of charge, including our schools and hospitals.

“We are peaceful protesters but the police repress us – and what we’re saying isn’t generally reported on the news channels but via social media. We went to the students occupying the rectorate of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, and people were arrested because we were taking them food. But this isn’t a political game, it’s a social demand that in any democracy the government is supposed to solve.”

Although the crisis affects every generation, it’s the youngest who are the ones who have grown up with the economic crisis and seen their dreams collapse. The country has already had its brain drain of architects, doctors and engineers, and now, even though they embody Greek ideals and language, the next generation to go abroad will be the artists.

As Papadoudis puts it: “My generation has better criteria to see where things are going and to be the first to protest. Everything has happened from my school – there are only 70 of us at the National, we don’t have a confrontational background, we’re not into politics, but we can see what will happen because we’ve lived through the economic crisis, we’ve lived through scandals like the artistic director of the National Theatre, Dimitris Lignadis, who resigned because of sexual abuse. We now say ‘no more’.”

Athens Concert Hall A: Inside the Megaron Athens Concert Hall

Photos by: Katerina Kaoustou

The students have tried to engage wider public debate by calling on the Union of Greek Actors and other unions to play a more active part in the fight, but aside from a handful of short strikes, they haven’t done a great deal. As Papadoudis points out: “I believe that what we’re seeing is a generational gap. At this point, it’s the students that have done so much, not the other workers in the arts sector.”

So not only is everything on the new generation’s shoulders, but it also finds itself at a bleak make or break point.

“We really do have nothing to lose,” says Papadoudis. “And that’s the best way to put it, because our working conditions are the worst. The Ministry of Culture has done nothing all these years to regulate our working spaces, rehearsals are not paid, wages are extremely low. In fact the majority of actors don’t even have the opportunity to work in theatre.

“In the past, workers in the arts sector didn’t protest much. But now that we have initiated a public debate about what type of art is being created, my generation will make political struggle integral to our future artistic creation.”

There’s an insane irony in the fact that Greeks need a high school diploma to qualify to study for a higher education degree that’s equivalent to a high school diploma. The most prestigious institution for theatre is the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, and there are the three state drama academies: the National Theatre in Athens, the State Theatre of Northern Greece in Thessaloniki, and the Municipal Regional Theatre of Patras – only the school of the National Theatre of Athens has a directing department. The private theatre academies are supervised by the Ministry of Culture and require entrance exams, often with high tuition fees.

The admission system to the state schools is fair but competitive because places are limited, and there are problems once they get in. Many lecturers are highly skilled but that doesn’t necessarily make competent teachers, plus they’re following an antiquated curriculum – even in the National’s new department of directing, which opened in 2018 – and the numbers of administrative and cleaning staff are low.

Kaoustou says: “On a basic level, students don’t have reduced fares on the buses, support for food, accommodation or books. For three years someone else has to shoulder all your living expenses, if you’re lucky. I’ve helped fellow students by buying them food because they could not support themselves – and that’s with me not in the best financial situation either.”

The students showed the way for their institutions where lecturers from all three state schools resigned en masse, a historic move that finally mobilised the media and led to – admittedly fruitless so far – consultation with the government.

“I believe in our movement,” says Kaoustou, “but I don’t expect any practical response from the government, whose decision proves its politics in every way – excluding the people and pushing the privatisation of health, education, culture and much more. In addition, general elections later this year make it even more difficult to meet our demands because Parliament will dissolve and there will be practically no government.”

Leaving Greece is becoming an unavoidable option for many in the sector. In the past, artists were forced to go abroad but that happened because of political oppression, not economics.

“What can you say about the tragedy of leaving our country and not being able to produce in our language?” asks Papadoudis. “A significant part of the meaning of national identity collapses. This has also happened in other areas the state has decided not to fund, like literature and education. The tragedy is that theatre is not being taught in primary or secondary schools, so we are also fighting against the barrier to understanding and learning Greek theatre.”

The Greek artists who are renowned abroad mostly do non-verbal theatre or dance, such as Dimitris Papaioannou and Iris Karayan. Back home, it’s mostly classical theatre and translations of foreign plays. The new plays that do get produced rarely expand on Greek culture nor push it in new directions. As Papadoudis sees it: “The state says to each artist: stay in Greece as long as you do translations of classical plays or touristic shows in the amphitheatres.”

While the students have closed down the National Theatre and met with the prime minister, at the same time they have been criticised for stopping people from seeing theatre. “But,” says Papadoudis, “we ask the question: what theatre are you actually going to see if theatre workers never have the same rights again?”

Tsiller: The National Theatre of Greece’s Tsiller Theatre in Athens – the banner says: “Occupation – Tsiller building” Photos by: Katerina Kaoustou

In fact the structure of Greek theatre is changing, he adds. “We have had theatre of protagonists and theatre of television stars, but the idea of ensembles is returning and this will come out of the student movement. Okay, it’s going to be really poor at the beginning, like Grotowski, like Karolos Koun, who created art theatre during the Nazi Occupation – unimaginable! – but then he was later funded by the state.

“Our very first step has to be to stop the discouragement. We will stop the mentality of the generation before us, where they were saying: if I do not work in a state theatre or in television, then I will be a waiter, I will find another career. We will regroup and create our own alternative institutions, but we will not be like an alternative state that is outside in the streets and parks. We will be a true theatre for the people. And because we are now politically engaged, we will ask the government for money.”

Because theatre professionals are treated as unskilled workers, their value isn’t recognised, says Kaoustou. “People think theatre is a hobby, meanwhile the capitalist system dilutes the arts because it’s not a material product that can be mass produced. So in this country, working does not guarantee you a decent salary, labour rights that are not violated, a living that tells you it is worth the effort – and which does not involve abusive work conditions.

“Our movement now embraces the needs of all Greek society and it has been embraced in return. It has created a space and time for a society that lost its voice and surrendered to an apolitical attitude to life. This is a victory and a beginning for change. We will speak until they hear us.”

As Papadoudis says: “We have been people with political interests or artists with inspiration. Now Greece’s artists are bringing both together to create a new future.”

Nick Awde is a journalist, playwright, editor, critic and producer. Based in the UK, he is co-director of Morecambe's Alhambra Theatre. Books include Equal Stages (diversity and inclusion in theatre), Mellotron, Women In Islam, and translations of plays by other writers. Much of his work focuses on ethnoconflict and language/cultural genocide.