Yugoslav Drama Theatre, Belgrade, premiere 2nd April 20022

Although there are only four of them, Ljubomir Simović‘s plays occupy the same status in Serbian theatre reserved for Shakespeare in British culture.

Simović, who continues to participate in the artistic and public life of Serbia, wrote his first play Hasanaginica in 1974, and the last one entitled The Battle of Kosovo in 1988. Like Shakespeare, Simović draws material for his plays from mythological, historical and national heritage.

The plays The Miracle in Šargan (1975) and The Šopalović Travelling Troupe (1985) are two of the most performed of his plays, which are almost always in the repertoire of some theatre in Serbia. They represent the proving grounds for success or failure of actors and directors. A production of a play by Simović can introduce us to the current interest of artists and provide the measure of the standard of theater. The Yugoslav Drama Theater has both titles in its repertoire, directed by the same artist – Jagoš Markovic.

The Miracle in Šargan is a play of complex symbolism. The plot takes place on two intertwining planes: the real and the spiritual. In one plane, we see characters from the social margins, the owner and visitors of the Šargan tavern on the outskirts of Belgrade; in the other, the ghosts of two Serbian soldiers from the First World War.

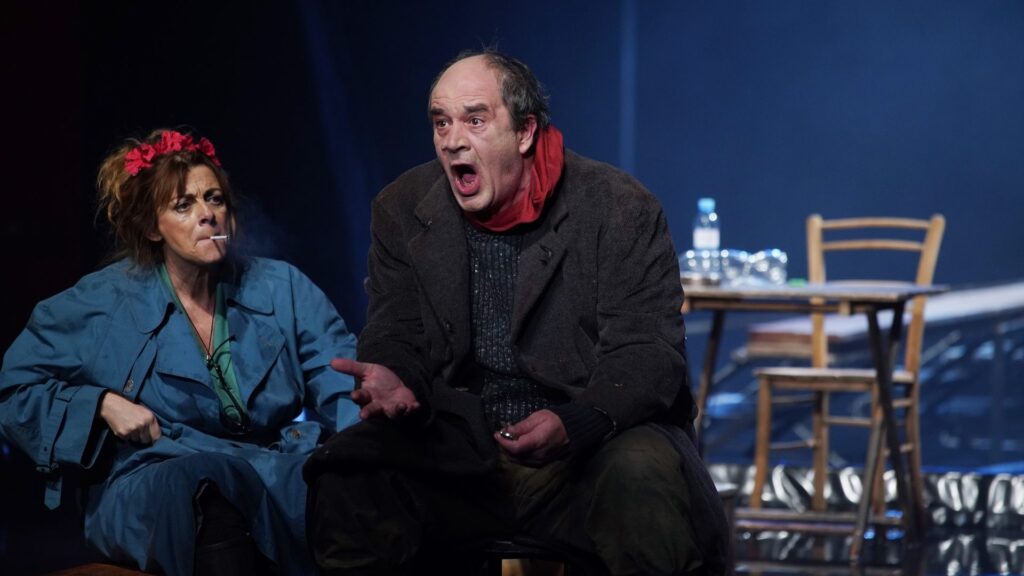

Cudo u Sarganu. Photo: Nebojsa Babic

These two worlds are linked by the character of the Beggar. He is a Christ-like figure who takes on the wounds, pains and sufferings of others – from ordinary toothache to the deadly wounds received in war, to a person’s psychological unrest. Depending on the interpretation, the Beggar may be a fallen deity, a deity who no longer understands the needs of humanity, a god distorted by people praying for the resolution of their personal problems, or a demonic figure. The sufferings that the Beggar takes on are an inseparable part of the identity of the characters in the Šargan tavern. With the loss of their pain, the characters lose their identity, and thus neither institutions nor relatives can recognize them.

Jagoš Marković is both director, scenographer and music selector of the production. He has flooded the Šargan tavern. Actors in rubber boots walk through a few inches of water. The reference to the biblical flood is obvious, but essentially completely ignored. Nothing and no one comments on the flood. One gets the impression that the director chose the water purely to achieve a visual effect. Marković uses water in a similar way in the production Wild Meat for the Belgrade Drama Theater.

Markovic’s choice of music is more suggestive. He chose sad folk songs to create the effect of sentimentality and melancholy. However, on two occasions, in the middle and at the end of the performance, one can hear the song of God Christ sung by two Serbian soldiers, and which Simović wrote for his play The Battle in Kosovo. The song adds the motif of Kosovo, the former Serbian province that declared independence in 2008, to the thematic framework of a play that treats wounds as an inalienable part of identity,

Choosing that song not only states that Kosovo is an inseparable cultural and historical part of Serbia, but adds one very provocative meaning. The song was sung and adopted as an unofficial anthem by members of the Special Operations Unit who allegedly participated in war crimes committed in Kosovo during the 1990s and were later linked to several assassinations, including the assassination of Zoran Đinđić, the Serbian prime minister. A possible provocation is that the production declares the worst crimes as an inalienable part of the identity of Serbian soldiers and everything they represent. However, it is the baggage that the song brings with it, the production itself does not pay attention to such meanings at all. It is as if the director, fascinated by its melody, decided to ignore everything that song represents.

Cudo u Sarganu. Photo: Nebojsa Babic

In his stage design, Marković tries to reduce the interpretive potential of the complex piece to a minimum. One of the main features of his directing is skilful playing with the emotions of the audience. He uses all available stage means to provoke a mood from tears to laughter. He achieves this through the suggestive invocation of ideological, political, social and cultural motives, but with a striking lack of attitude or elaboration towards the context he invokes.

Everyone can find what they want in Markovic’s performances. A Serbian nationalist and cosmopolitan, a fan of popular culture and a supporter of high art, can equally enjoy his productions. His is an expensive, populist approach to directing that enriches the theatre’s repertoire with a spectacle based on a classic dramatic text while reducing it to its superficial layers.

This people-pleasing directorial approach emphasises the humour in the piece; several of the actors use overemphasized expressions to further simplify Simović’s drama. In the role of Ikonija, the owner of the Šargan cafe, Anita Mančić tried to find as many opportunities as possible to make a humorous gesture. Miodrag Dragičević shouts a lot, and waves his hands even more in the role of Anđelko. Marko Janketić is more moderate with these gestures in the role of the opportunistic Mile. He falls asleep on the chair twice, falls off it, gets wet and leaves pretending that nothing had happened. He thus depicts this inconsistent character, who changes his political position for his own benefit and denies that he was ever a passionate supporter of the once victorious and now losing side.

As well as insisting on the humorous aspect of the text, Markovic’s direction is predominantly concerned with trying to be pleasant, in terms of emotions and sentimentality. The two soldiers, portrayed by Ljubomir Bandović and Aleksej Bjelogrlić, are important in this respect. While Bandović interprets a cautious soldier who adheres to military discipline, Bjelogrlić plays a person who allows himself an outpouring of emotions and daydreams. Sanja Dragičević (Gospava), Tamara Marković (Cmilja), Nebojša Dugalić (Vilotijević) and Boris Isaković (Skitnica) created authentic characters who skillfully control the transition between humor and sadness, despair and hope. The four of them deliver complex, nuanced performances that transcend Marković’s simplified directing.

Nenad Jezdić plays the character of the Beggar to perfection. He mutters and mumbles, speaks as if his character has no teeth, often repeats the same words, speaks to himself, addresses others as if speaking to himself. He leaves the impression of someone who really has spent most of his life on the street, a lonely man in a crowd, addressing everyone while being listened to by no one. The symbolic function of the Beggar, both a Christ-like and demonic figure at the same time, was annulled by the brilliantly realistic performance of Nenad Jezdić. In this case, excellence in performance became a purpose in itself, and Simović’s play served as a vessel for demonstrating his acting skills.

And that is the essence of this production. If you want to laugh and cry in the same evening, and watch some great performances, you will love it. If you want a provocative, brave, truly artistic vision of everything that Simovic’s text can be, you will need to be patient and wait for another miracle in Šargan.

Credits:

Adaption, direction, set design and music selection: Jagos Markovic

Costume: Lana Cvijanovic

Cast: Anita Mancic, Tamara Dragicevic, Sanja Markovic, Milos Samolov, Marko Janketi, Miodrag Dragicevic, Nenad Jezdić

For tickets and further information, visit: JDP.rs

Further reading: 67th Sterijino Pozorje – a critical dialogue

Andrej Čanji is a theatre critic and theatrologist based in Belgrade.