Photo: Ferdi Limani

In November, a group of Kosovar, Serbian and American actors set out on a tour of the Balkans with a modern reworking of a Greek tragedy. Natasha Tripney joined them on the road.

“What a way to make a living.”

Dolly Parton’s Nine to Five is playing over the speakers as our minibus winds its way through the outskirts of Prishtina. One by one the passengers – all members of New York’s Great Jones Repertory Company – join in as the driver negotiates the evening streets, heading towards the heart of the city.

The Great Jones company have come to Kosovo from the LaMaMa Experimental Theatre Club – founded in the 1961 by the legendary Ellen Stewart – to perform Balkan Bordello, a fevered reimagining of the Oresteia by Kosovar playwright Jeton Neziraj.

As part of an ambitious international co-production between LaMaMa, Kosovo’s Qendra Multimedia, Serbia’s Atelje 212 and My Balkans, also based in New York, the US performers – Onni Johnson, George Drance, Eugene the Poogene, Valois Mickens, John Maria Gutierrez, Mattie Barber-Bockelman, and Matt Nasser – are part of a larger company that includes the Kosovar actor Verona Koxha and the Serbian actors Ivan Mihailović and Svetozar Cvetković and, over the past week, they have visited five cities: Prishtina, Gjilan, Ferizaj, Tirana, and Belgrade. Each night they’ve performed in a new theatre and had to negotiate a new stage. The company has spent a lot of time on buses, eating tangerines and salty Balkan snacks as the GPS sent them on scenic, if unintentional, detours through southern Serbia. They’re heading back to Prishtina for two more nights after which they will return to New York. In April 2022, the show will play a further 10 nights in La MaMa.

For many of the LaMaMan company members, this is not their first experience of performing in the Balkans. Stewart toured work all over the world, including the former Yugoslavia. The Great Jones Rep – named for Great Jones Street, where La MaMa’s rehearsal building is located – was formed in 1972 Stewart with the director Andrei Sherban and the composer Elizabeth Swados, to support their work, though as Johnson explains, it was not a rep company in the traditional sense. “It’s more of a collective.” The word that most often comes up when, however, when talking to the actors about it, is “family.”

LaMaMa’s landmark work of the 1970s, created by Serban and Swados, was Fragments of a Tragedy: versions of Medea, Electra and, finally, the Trojan Women, created using a text based on ancient languages. Initially they used ancient Greek, but by the time they reached the Trojan Women, they were using a mix of ancient languages and invented sounds designed to un-anchor the play in time and place, and in doing so, to create something universal. “Because the language doesn’t belong to anybody, there’s no alienation that comes from not understanding,” says Johnson. This last piece, The Trojan Women, has become a signature show of LaMaMa, staged in more than 30 countries around the world. Johnson and Mickens were part of the original cast of The Trojan Women and performed it at Belgrade’s BITEF festival in 1975.

“Because of the themes that run through the original play – war, genocide, displacement, the plight of women and children – we thought it would resonate with societies that had experienced conflict,” Johnson explains over coffee in a café in Prishtina. But, over time, their thinking about the nature of their mission as a company evolved. They’ve become increasingly uncomfortable with the idea of ‘post-conflict’ societies. After all,” she says, “there’s nowhere that’s not in conflict.”

The show eventually became the basis of the Trojan Women Project. Instead of swooping in and performing, with its overtones of colonialism, they started working in collaboration with actors and creatives from countries including Kosovo, Guatemala and Cambodia, “to give the piece to people and find ways to incorporate elements of their culture and their music.”

Johnson and Drance came to Kosovo in 2017 and 2018 where they worked in conjunction with arts activism group ArtPolis, and a company of Albanian, Serb and Roma actors and musicians. They eventually performed The Trojan Women in Prishtina (Johnson was initially sceptical about the choice of location, in front of the National Library, a building with an unfair reputation for ugliness, but was eventually won over), as well as in North Mitrovica and in Prizren.

Mickens and Drance had previously toured with Stewart to Belgrade, Dubrovnik and Orhid in 1996, when the aftermath of the war was still palpable, hanging heavy in the air. Eugene the Poogene felt this too, when he performed in Belgrade’s National Theatre in 2001. “I was much younger then, but I couldn’t believe that people had lived through this.”

After Stewart passed away in 2011, the company spent a few years “self-assessing,” explains Johnson. It was decided they would work with other directors to create new work. LaMaMa and Qendra Multimedia had established a relationship during the Trojan Women project, facilitated by the indomitable Maud Dinand, who had worked in Kosovo with the United Nations and ties to LaMama stretching back to the 1970s. After Jeton Neziraj’s play 55 Shades of Gay was performed at LaMaMa in 2019 by a cast of actors from Kosovo, both companies decided to build on this relationship. The decision to work together on Balkan Bordello came about during the pandemic. For some company members, it’s been the first time performing in front of an audience in almost two years.

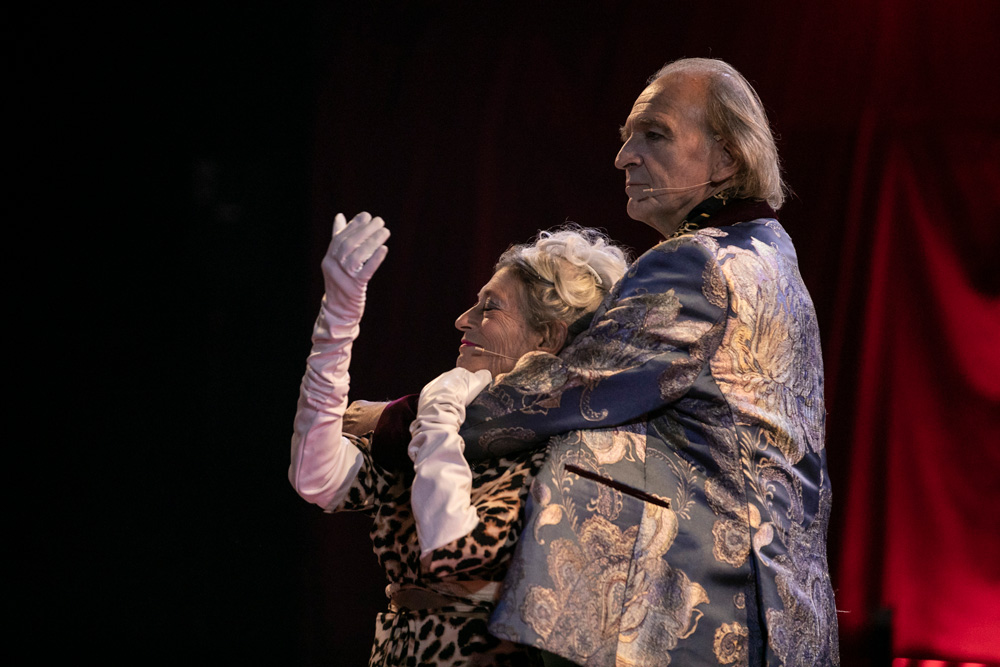

This tour has been intense, dizzyingly so, to the point that they sometimes needed to double-check which country they were in on any given day. This is fitting as Balkan Bordello is an intense production. Jeton Neziraj has relocated Aeschylus’ play to the Balkan Express Motel. Agamemnon (Drance) is a military commander, returning home after committing heinous acts in battle; his wife Clytemnestra (Johnson) has taken up with the poet and would-be intellectual Aegisthus (Cvetković) in his absence and now wants to rid herself of her brutal husband who slew their daughter Iphigenia to court favour with the gods. He brings home Cassandra (Verona Koxha) as a human trophy, slung over his shoulder. Pylades (John Maria Gutierrez) is now an international interloper who wants to ‘civilise’ the locals through the medium of dance. The motel’s resident singer Valois Mickens sings jagged ballads as Clytemnestra plots to off Agamemnon. With its fringed crimson lampshades and ugly rugs, the Balkan Express may not aesthetically resemble The Shining’s Overlook Hotel but they are both spaces that hold onto ghosts. The staging by Blerta Neziraj is carnivalesque and full of intentional mess; by the end the stage is carpeted with glitter, dollar bills, business cards and ribbons of toilet paper.

Onni Johnson in Balkan Bordello. Photo: Ferdi Limani

Neziraj’s play has also gone through several iterations. Originally titled O.RESTes in Peace (a wordplay that was soon dispensed with), a version was staged by Stevan Bodroža at the National Theatre of Montenegro in 2015; in 2017, when the Serbian director András Urbán staged a production at the National Theatre of Kosovo, angry veterans protested outside. This new version is less explicitly rooted in a post-war Kosovo context and its reception has been markedly different. When it premiered at Prishtina’s Oda Theatre, an underground space – a former night club within the city’s Palace of Youth and Sports – on 3rd November, instead of protestors and police cordons, a line of black-suited security personnel streamed into the theatre bar along with the audience. As Blerta Neziraj’s work often punches through the fourth wall, this felt like it could be a scene from one of her productions, until it became clear they were accompanying Kosovo’s Prime Minister Albin Kurti. When the announcement went out that everyone – including the prime minister – should turn of their mobile phones, the cast remember thinking it was a joke, only realising afterwards. “I offered him some rakija at the bar,” recalls Matt Nasser. Kurti politely declined.

Bringing the show to the stage has not always been a straightforward or easy process. Even without the complicating factor of the pandemic, the forging of a cross-cultural company presents challenges. The cast have very different acting backgrounds, different approaches to performance, they’re engaged in different conversations about representation (“We’re talking about pronouns and they’re 15 years out of a conflict,” says Eugene) and have different expectations in the rehearsal room. (“They like to prepare a lot before the rehearsals, to have a silence before the show, which we don’t have,” observes Koxha of her US co-stars). While the process was something of a learning curve for everyone, on stage these differences make for an excitingly texturally varied production. Cvetković, a major star of Serbian stage and screen, has a grandiose presence, marrying classicism with touch of the bouffon. As the poet Aegisthus, he speaks in recitation, a man determined to share his verse with the world. He uses his voice as an instrument, stretching out words, shrieking, booming.

By contrast, Ivan Mihailovic – star of popular Serbian TV show Vojna Akademjia – is intense and volatile, like a cola can, shaken up and ready to pop, exuding what might be termed a stereotypically aggressive Balkan masculinity. John Maria Gutierrez, as Pylades, is more intimate and conspiratorial, interacting with the audience, enthusiastically informing them about his dance studio in Berlin. Audience interactions can be a tricky, he explains, but it worked well in most of the venues they played. He learned early on that eye contact is key to gaining people’s trust in these exchanges. At one point, his character has to ask an audience member if they killed someone in the war, and at first, he wondered if this would cross a line, but the audiences embraced the transgressive humour of the scene, due in part to the way his Pylades so effectively sends up the figure – all too familiar in these parts – of the well-meaning ‘international.’

The tour presented the performers with logistical and practical challenges too. While the bunker-like Teatri Oda has an immersive feel, with cabaret-style tables dotted about the stage, the other theatres on the tour were more conventional end-on spaces, with Ferizaj’s Teatri Adriana a particularly compact space. “Andrei Sherban used to talk about some spaces are talented and some spaces not talented,” recalls Johnson; she was pleased to see how well the show worked in some of the venues. As Koxha is from Ferizaj, there was a particular resonance for her and the company in playing her home theatre and many of the actors regard this audience as one of the warmest responses they encountered.

The next stop on the tour was Tirana’s Experimental Theater, another small space. After that they went straight to Belgrade for a two-night engagement at Atelje 212, a far larger space – and Cvetkovic and Mahailovic’s home theatre. Here they had the luxury of two nights in the venue, a chance to get a stronger sense of the stage’s dimensions. It paid off, with the second night one of the strongest of the tour. With the exception of the Centre for Cultural Decontamination (CZKD), it is rare for theatres to host work in Serbia, so this collaboration with Atelje 212 is something of a landmark.

As is often the case on tour, a closeness formed between the company. They created “a safety net of love,” explains Eugene the Poogene (“I wanted to be Eugene the something and I thought blue jean was a little too cliched so I went with poo,” he says, explaining his name). He has the added security of being with “my family of 20 years” and this sense of safety allows him to take risks as a performer. There’s a scene in the play in which Orestes strips naked and curls on the floor over the body of his mother, smeared in blood – a kind of reverse-birth. This was the first time he had performed naked and he was nervous about this. “I don’t know if too many men get naked on stage here,” he said, but “I felt really supported by the house.”

Initially Verona Koxha, the only Kosovar member of the acting company was apprehensive about working with actors from the States and from Serbia for the first time. “I was a bit afraid, because this is going to be different, this is going to be hard for me, because of the language and everything. But it was much better than I expected it to be.”

She was worried that some people might question her choice to work with Serbian actors and perform in Belgrade, but she was pleased to make professional connections and feels it was an important project in which to participate and she found that “it was so easy to, to fit in and to make a good connection with them. They were so supportive. I felt free to try new things.”

This was particularly important in one scene in which her character is raped on stage. Though Drance’s Agamemnon never touches her – all he does his unbuckle his belt, it is Koxha who conveys the terror and violence of the scene. There’s a responsibility in performing such traumatic material, she says, particularly in Kosovo. Recently a friend gave her a book documenting the stories of women raped during the war. “I couldn’t read more than three story, because I started to shake,” she says. It was important to make her performance as hard and raw as possible. “Because I needed to express the kind of terror, the horror, to reveal it to the audience. I wanted to show what people have been through all these years, and how they’re not allowed to talk about it because people will judge them. I wanted somehow to give that feeling to our audience – to get them to see with the eyes of someone who is getting raped. And I wanted to make this as as real as possible.”

Photo: Ferdi Limani

She believes that Balkan Bordello’s power lies in its universality. “It is not only about the wars we have in the Balkans,” she says. “During the time that we are working here on this project, somewhere in another country a war is happening.” While she was preparing for her role, she was thinking about Cassandra’s powers – and her powerlessness. “Now, for example, in Afghanistan, I see girls who are not allowed to go out of the house, they are not allowed to go to school. And that’s a very sad thing.” That’s the message of the show, she says, “this is all the wars that are happening and have happened before. This is not only for us.”

Though it has not always been plain sailing, Johnson remains struck by “the miracle of having Serbs and Albanians and Americans working together. We don’t we don’t dwell on that, but that’s amazing.” For Eugene, after almost two years of cultural and social isolation, “the ability to connect with other cultures in a creative way has been super-fucking-therapeutic and super- profound and needed.”

The night after the last performance in Prishtina, the temporary family gather in a restaurant for a final meal and one last shot of raki. There’s an awareness that this intense period of living on top of one another, travelling together, and working together, is drawing to a close, like a soap bubble on the cusp of bursting, but also the comforting knowledge that the journey isn’t over yet – a family reunion is on the cards.

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0