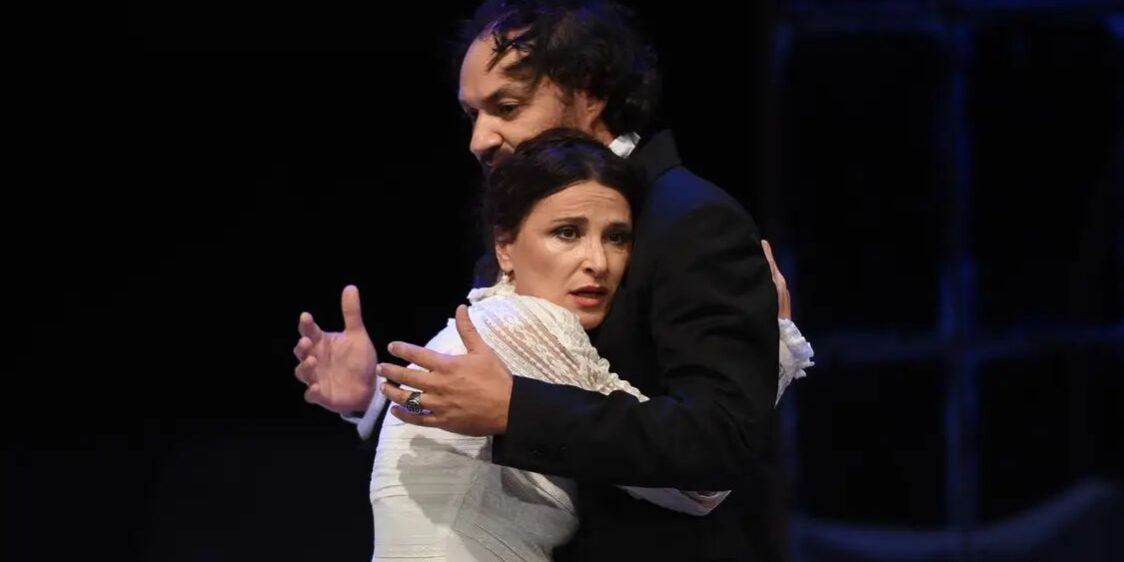

National Theater of Albania, premiere 15th October 2022

Only three premieres were held last year at the National Theater of Albania. And once again a new artistic season began with no programme in place. During an interview in the spring, the director of the National Theater, Hervin Çuli, said he will not run for a third term (after two mandates appointed by the government).

The most recent production was Çuli’s own production of Chekhov’s Ivanov. The play was written on commission (a word unknown to our theater in Albania) for the Korsh Theater in Moscow, but when it was staged there, Chekhov did not like it at all. He complained about the show in a letter to his brother, writing, “It appears like the actors don’t know what they are talking about.” He revised the play considerably as a result.

Kristo Cala’s set design creates a commodious and wide space for the performance. Dim lights dangle from huge glass windows, which lead out into a spacious garden with trees that appear to have been covered in snow. All aspects of the design, the colours and costumes, evoke the spirit of Russian winter.

Nikolaj Ivanov, once a successful man, full of humour, passion, and love, has now transformed into a black stain of a man, who darkens everything he touches. As Ivanov, Dritan Borici walks the line between being the main protagonist and letting the spotlight fall on the other characters, but as a result, his Ivanov appears fuzzier as a presence. Ivanov no longer feels any love for his wife Anna, (played by Luli Bitri). Five years ago, moved by his love and enthusiasm, she left her family and her Jewish roots behind to marry Ivanov and convert to Russian Orthodoxy. Now she has tuberculosis and will soon die.

Her disease is revealed by the ‘honest’ doctor Eugene Lvov (played by Laert Vasili). Even the most honest of honest people would find his honesty to be annoying. And while Ivanov does not find this doctors honesty disturbing (on the contrary, he uses him as a stick with which to beat himself), Count Matthew Shabelsky, Ivanov’s maternal uncle (portrayed by Alfred Trebicka), finds it intolerable. Trebicka manages to create the geriatric buffoon persona of the Count.

The neighbour’s yard always has greener grass. The Lebedevs’ home is an ‘ongoing’ party that never ends. Mrs Zinaida (Flaura Kureta) is frugal but wealthy, and her husband, Paul Lebedev (Neritan Licaj), is the chairman of the rural district council, confidant and a good friend to Ivanov, who even offers to pay the debt Ivanov owes to his wife – of course without her knowledge. In this garden blooms a flower, the couple’s 20-year-old daughter Sasha, played by Elia Zaharia, who is fascinated by Ivanov. In the eyes of the young dreamer, he is in a desperate need of her heroism to save him from his sorrow and the dark cloud that surrounds him. (However, it is difficult to tell how old Licaj is compared to his daughter Zaharia – a few white hairs on his head might help).

Later in the play, Ivanov almost marries Sasha, the daughter of his friend Paul Lebedev. But even though the wedding is set, it won’t happen. After dragging himself through the depths for such a long time, he finally finds the ‘courage’ to act and escape the grasp of the pit of despair into which he has fallen, by committing maybe the most morally ambiguous act in human history: suicide. (In Chekhov’s first version of the drama, Ivanov marries Sasha and finds some satisfaction, while in the second version, Ivanov gives up on marriage and takes his life.)

Ivanov at National Theater of Albania

I’m not sure what Chekhov would think if he saw the National Theater production of Ivanov. The play runs for three hours and a half with two intervals. Returning to the theater after these intermissions was much like returning from a coffee break at work. Ivanov and the other characters are portrayed by the actors in a manner that appears ‘proper’ yet the performances are mushy and lack substance. With such a compelling narrative, the director Culi could have done so much more, but it doesn’t seem that this was ever his goal.

The personality of Ivanov is a psychological puzzle. No stereotype would fit his character well. Though he has acute sensitivity to the pointlessness of life, he also shows complete insensitivity to the death of his wife. The desire of the two women in his life to save him, only deepens his desperation, however it is clear that his behavior is unconscious and unintentional.

Ivanov’s character is actually fairly ‘contemporary’; for the time it was written. The tragi-comic play vibrates at the same frequency as the majority of the great Russian works of the era, and like all masterpieces, it also resonates with a modern audience.

But it seems to be too much to ask of the National Theater and of Çuli to bring something more contemporary to the play. Not because it is impossible, but more because there hasn’t been any attempt to do this for many years.

Ivanov is a theatrical masterpiece, this is not in doubt, but perhaps it’s time for the National Theater to start ‘speaking Albanian’ as well as staging masterpieces, to take a pass on the samovars, the counts and countesses for a while. And maybe in doing so, bring new life to the stage.

Flamur Dardeshi is a freelance writer based in Tirana. He has contributed in the areas of translation, analysis, and poetry. His main fields of interest are literature, cinematography, and theatre.