Mladinsko Theatre, premiere 16 May 2025

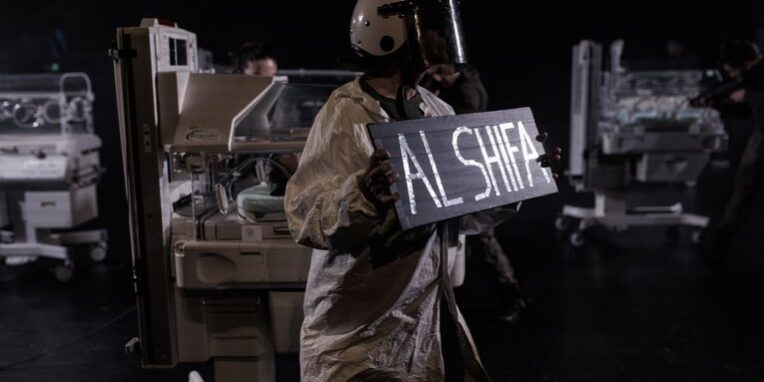

A rebel, a radical, or a revolutionary. These are words often associated with the name Oliver Frljić – a theatre director, who up until recently was co-artistic director of the Maxim Gorki Theatre in Berlin. Now Frljić returns to the Mladinsko Theatre in Ljubljana with the premiere of Incubator, a performance which addresses the attack on the Al-Shifa hospital in Gaza.

In his previous work, like 2010’s Damned be the traitor to his homeland!, or Mass for Yugoslavia –originally known as The Ristić Complex – he touced on topics of Slovenia and Yugoslavia. His new premiere however doesn’t engage with the local myths of the country where it premieres, rather the ongoing conflict in Gaza.

Like any of his projects, it has the character of a political manifesto. In keeping with the idea of theatre as a “frontex for ideas,” the play becomes a defender of democracy and human rights, explicitly opposing colonialism and violence. The central theme, however, is the deaths of children that occurred when the Al-Shifa hospital was cut off from electricity. Not having access to diesel to power the generators, infants died in the incubators designed to preserve their life. It is around the theme of children’s deaths – and death itself – that Frljić constructs almost all the scenes.

The structure of the performance consists of scenes that are not connected by a linear narrative, yet together form a coherent interpretative whole. In fact, the phrase non-linear narrative opens the performance, while it ends with the phrase semiotic disobedience. These slogans mirror the structure and character of Frljić’s projects. Incubator is based, which is also typical of the Croatian director, on quick transitions between humour, light scenes and brutalism through which the performance does not affect the emotionality of the viewer, but creates a distance.

Frljić operates within a form of theatre that could be described as post-theatre, where theatricality and theatrical means are reduced to a minimum. He likely does this because the effect of a performance as manifesto has a greater impact than theatre in the traditional sense. This reduction of means also supports the narrative structure of political theatre, which characterizes all of the Croatian director’s productions. Provocative scenes and controversial, radical theses are emblematic of Frljić’s work, and they resonate precisely because of the specific post-theatrical form in which the language of the performance is simplified and the sense of distance increased. One Polish scholar, Dariusz Kosiński, even called this approach an increased Brechtian verfremdungseffekt. This distancing usually helps Frljić in creating scandal but in this case, the formal distance was compounded by a cultural one.

The main props, and in many scenes, also the central elements of the set design – are the titular incubators, which shift meanings depending on the context of each scene. At times, they serve their literal function as life-support machines for new-borns. In another moment, they transform into a puppet theatre, staging a conversation between two new-borns who are fully aware of their impending death. Elsewhere, they become war machinery: actresses sit atop them holding paper rockets labelled “GAZA,” mimicking rocket attacks. The dolls are another key prop, sometimes serving merely as static elements, and other times being brought to life by the actors. Throughout most of the performance, the actors wear green military uniforms marked with “IDF,” imitating the behaviour of Israeli soldiers. Music plays a particularly significant role in this production. Its dramaturgy is carefully constructed and intricately tied to the emotional tone of each scene. One example is a Nirvana song Smells Like Teen Spirit, accompanied by band’s iconic album cover featuring a floating baby (that resonates with the performance’s core themes). Music is present in almost every scene, either as an active force shaping the action or as an atmospheric background with equal narrative weight.

The performance is a collection of various scenes such as a dabke dance with incubators, cruel jokes about Palestinians, IDF soldiers taking pictures of themselves with dead bodies, or painting the borders of Israel and Palestine on an actor’s naked body. The body is both exposed and degraded in Incubator for critical purposes. This is particularly evident in the cooking scene. Vito Weis and Klemen Kovačič act out a parody of a cooking show, during which they talk about the value of a Palestinian hostage, comparing it figuratively to the amount of meat used to prepare an oriental dish. The body also recurs in a scene of an imaginary letter from an Israeli woman to a Palestinian boy from whom she received a heart. This is an exceptionally powerful sequence that addresses the issue of harvesting organs from dead Palestinians for Israeli organ banks. At the same time, it shows the paradoxical bond between the two peoples, but a bond based solely on carnality and only possible after the death of one of the parties.

An interesting local touch is the story of Draga Potočnjak, who undertook a 10-day hunger strike as a sign of solidarity with Palestine and to draw attention to the war. In an artificially arranged scene, actors from the Mladinsko theatre play the role of the pro-Israeli public, accusing Draga of a lack of authenticity, hypocrisy, antisemitism and a selective approach to war topics. However, this scene leads to a self-negation of the previously constructed narrative and undermines its own message.

Incubator, Mladinsko Theatre

The performance’s anti-war message, especially its criticism of the Israeli military and Benjamin Netanyahu, is most clear in the scenes set in the hospital and around the incubators. The IDF soldiers are portrayed as soulless fanatics, adhering to an ideology that labels children as terrorists. In a scene of a raid on Al-Shifa, they discover a laptop containing footage of the attacks on twin towers, which serves to justify their crimes. In the final scene, a photo of Benjamin Netanyahu with his new-born grandson appears on stage. As in the earlier cooking scene, the director again emphasizes the sharp contrast in how Israel and the West value human life based on whether it belongs to a Palestinian or an Israeli.

Frljić may have provoked another scandal with these scenes, as he clearly takes a strong stance in support of Palestine and against Israel. Much of the performance portrays Israeli citizens as entirely consumed by their own ideology and by propaganda imposed by the authorities. However, this reflects only the most radical segments of Israeli society and fails to capture the full diversity of a nation with a complex history and a wide range of narratives. Frljić deliberately focuses on the most extreme cases to make a point. One could argue that there is a risk this performance might be seen as antisemitic. However, the director does not target Jews as a nation. As in all his work, he critiques nationalist narratives and how they can overshadow the human perspective. He highlights extreme cases to draw attention to what he sees as urgent realities – such as the deaths of children in Gaza. Similarly, in Poland, he chose to portray only the darkest aspects of the Catholic Church without exploring the deeper role of faith in Polish culture. Such simplifications and bold statements are typical of his theatre, intended to provoke and challenge.

However, there is still a question of function of his theatre. Slovenia is among the few European Union countries that do not support Israel’s military action. This fact that was clearly felt during the performance. In a scene of accusing European leaders of disregarding the International Criminal Court the Slovenian government was not mentioned. How does such a lack of local context affect Frljić’s work? The Croatian director is known for deconstructing national myths and bringing to light topics that are sometimes marginalized or deliberately silenced in a given country. Yes, the Slovenian government still does not have a clear and strong position on Palestine, but the public mood, especially in Ljubljana, is leaning towards pro-Palestinian. In many places in the capital one can see graffiti expressing solidarity with the Palestinians, much more often than slogans supporting Ukraine (as in other post-communist countries).

This time, however, the impact of Frljić’s post-theatre appears diminished. It seems that his work is most effective within a specific cultural and political context, particularly when it remains closely tied to the local scene. When removed from that context, and in the absence of scandal or confrontation with national sensibilities, his political theatre loses its activist edge. Consequently, the cultural and societal discourse his productions typically provoke in the media following a premiere, fails. I write this as Israel continues its attacks on Gaza that is a stark reminder of the ongoing need for theatre to engage with such topics. The question that remains, then, is how?

Credits:

Director: Oliver Frljić// Dramaturgy: Goran Injac// Set design: Igor Pauška//Costume design: Slavica Janošević//Assistant director: Bor Ravbar//Choreography consultant: Dragana Alfirević//Lighting design: Kristina Kokalj//Music selection: Oliver Frljić

For further information, visit: Mladinsko.com

Further reading: Oliver Frljić: “The essence of my job is to be critical”

Karolina Bugajak is a theater critic from Poland, currently living in Ljubljana. She studied culture and contemporary art at the University of Lodz. The title of her master's thesis was "Theatricality and Exaggeration. Camp aesthetics as a strategy for creating new identities in the plays of Grzegorz Jaremko". Her main theatrical interests include topics such as institutional criticism, the representation of marginalized groups in plays, and most recently the theater of the former Yugoslav states.