Teatri Oda, Prishtina (premiere at City Theatre Gjilan, 17th October 2025)

Kosovo and South Africa could not be farther removed geographically, but human suffering knows no bounds or boundaries. Reconciliation has been a key word in both these places for decades. Performed in English, Albanian, and Zulu, Jeton Neziraj’s Under the Shade of a Tree I Sat and Wept – a coproduction between Kosovo’s Qendra Multimedia and South Africa’s Market Theatre – is a heartfelt piece about a plight that transcends continents.

The actors are wandering around the stage before the show starts, stretching and shaking their limbs, as the audience members come in. They recall a time in the mid 1990s when the Truth and Reconciliation Committee (TRC) in South Africa put survivors and victims’ relatives face to face with perpetrators after apartheid. In the span of a few minutes, they manage to squeeze in numerous stories of horrors that were done. The effect of these stories being told by South African actors is a reality check.

People sit on the two opposite sides of the stage, in what looks like a debate club. There is talk of restoration and reparation as potential cures and a sure-fire way towards reconciliation. Real names are mentioned, and real stories are told of unspeakable things. What a species we are to do such things to each other!

“Tell us what happened that day!”, Gontse Ntshegang cries. Chilling answers ensue. “They poured acid on my son… they beat me up every day while in prison… naked and rolled-up in a carpet for days… ” Bishop Desmond Tutu is heard speaking, as real images of TRC sessions – survivors confronting their torturers and waiting for justice to come – are played in the background. “They waited, but only tears came…”, says Kensiwe Tshabalala walking slowly, her eyes glued to the floor. At some point the actors start speaking in Zulu. Alongside their narration, there is music, care of performance artist Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu, sitting majestically before a number of musical instruments, accompanying every phrase and every pause. As the soundtrack adjusts to the narratives, it carries the weight of a thousand words.

And then the stories hit home for the audience in Prishtina, as the Albanian narrators take to the stage. They remind the audience that, around the same time in the mid’90-es, with the threat of war looming, nearly 2000 families in Kosovo had been engulfed in blood feuds for years. A centuries-old honour-based vendetta stemming from the Kanun, aka the medieval ‘hand of the law’ in Albanian society, ‘gjakmarrja’ literally means ‘the taking of blood’. In 1990, the number of family members involved in blood feuds, by right of family, neared 30 thousand, or 4% of the Kosovo population – an alarming figure for a country so small.

Under the Shade of a Tree I Sat and Wept

“My dad was killed in a pointless squabble, while my mom was pregnant with her tenth”, says Ilire Vinca. “She was a heroine, my mom,” she continues peacefully, “although she was quite small…” The real family story unfolds, with the gory prospect of six sons being marked for death as soon as their bodies get taller than a rifle. The distant staccato of a flute carries across the stage, sombre and mournful.

And, then, cut! The actors come to an abrupt stop mid-scene, as the figure of the director (played by Les Made) congratulates the cast and delivers some excellent news: there’s pizza for lunch! It’s a shocking halt to a piece that was deep in raw emotion a second ago, the realization dawning that this is a ‘play within a play’. The actors eat, drink, and laugh cheerfully, sneering at the play they’re performing. Reconciliation… what? Ah well, the world loves a good story about forgiveness, right? Who cares about truth, anyway! On and on they go.

The narrative resumes with the announcement (by Gontse Ntshegang) that, after TRC, South Africa became ‘a factory of happiness’. Following this, three mothers sit in a courtroom where they’ve been called to testify on their sons’ murders. Long veils covering their heads fail to cover the pain on their faces, as the room also holds the perpetrators – both white and black. “They told me to kill them, I just followed orders” says a black perpetrator (Les Made, once again), before delivering a profuse apology to the grieving mothers. Seeking absolution, he comes to wash their feet, but one of the mothers vehemently refuses and kicks the basin. He retreats in silent remorse, looking as if he wished the earth to swallow him whole.

One of the Albanian narrators (Arben Bajraktaraj) brings us back to Kosovo, where, simultaneously with the TRC trials on the other half of the globe, an event of major proportions is underway. Almost half a million people have gathered to witness the pledges of feuding families to stop the cycle of violence. ‘Forgiveness is the highest act of courage’, are the words of renowned professor Anton Çetta, a key figure of the movement, which was initiated by women. Yet, beyond the collective tears of joy, forgiveness remains difficult for the Albanian men expected to take revenge. The shame would be unbearable. ‘When I shook the hand of reconciliation, it got darker than the dead of night’, utters Arben Bajraktaraj with a gloomy face.

The real heart of the reconciliation process are, of course, women. ‘If I find my father’s murderer sleeping, I will cover him with a blanket’, says a young woman with a soft smile. Though, by Kanun, a woman has no right to forgive her father’s blood, it’s the thought of losing her brothers that makes her brave enough to challenge tradition. ‘Today my thriving family counts up to almost a hundred members’, she continues gleefully. ‘When my grandchildren ask me to tell the story of how I forgave, I tell it like a fairy tale… once upon a time…’ She ends up mouthing the words, her voice hushed and muffled, until glee faints into mute lament.

Back in South Africa, the TRC courtroom is still in session with an unusual next witness in line: a famous painter. She’s a white lady smoking a cigarette underneath a head of feather-adorned hair. Her self-confessed crime: there isn’t one single black person in her paintings! The absurdity of her confession is in stark contrast with the plight of apartheid.

Gontse Ntshegang appears wearing a dress made of blue plastic bags – a reference to bags used to suffocate women during apartheid. As she is joined by the other actors in similar dresses, she starts to sing a song of pain. The performers move in unison, like a blue wave in the background. Then the director yells ‘cut!’ again, because the scene is ‘too pathetic’. He refers to the play as ‘fake stories from 30 years ago’, adding that no one is interested in the truth anymore. ‘We just put it on stage, and people love it’, he quips. At this point, a sense of awareness seems to emerge within the actors’ conscience. ‘Wait a minute… truth means something’, says Ema Andrea. ‘We can’t just throw the past away’. One of them brings up a sign that says ‘Truth will set us on fire!’. The absurdist jazz in the background fits seamlessly with this bona fide moment of truth. Ultimately, injustice has nothing to do with colour, they concur.

Under the Shade of a Tree I Sat and Wept

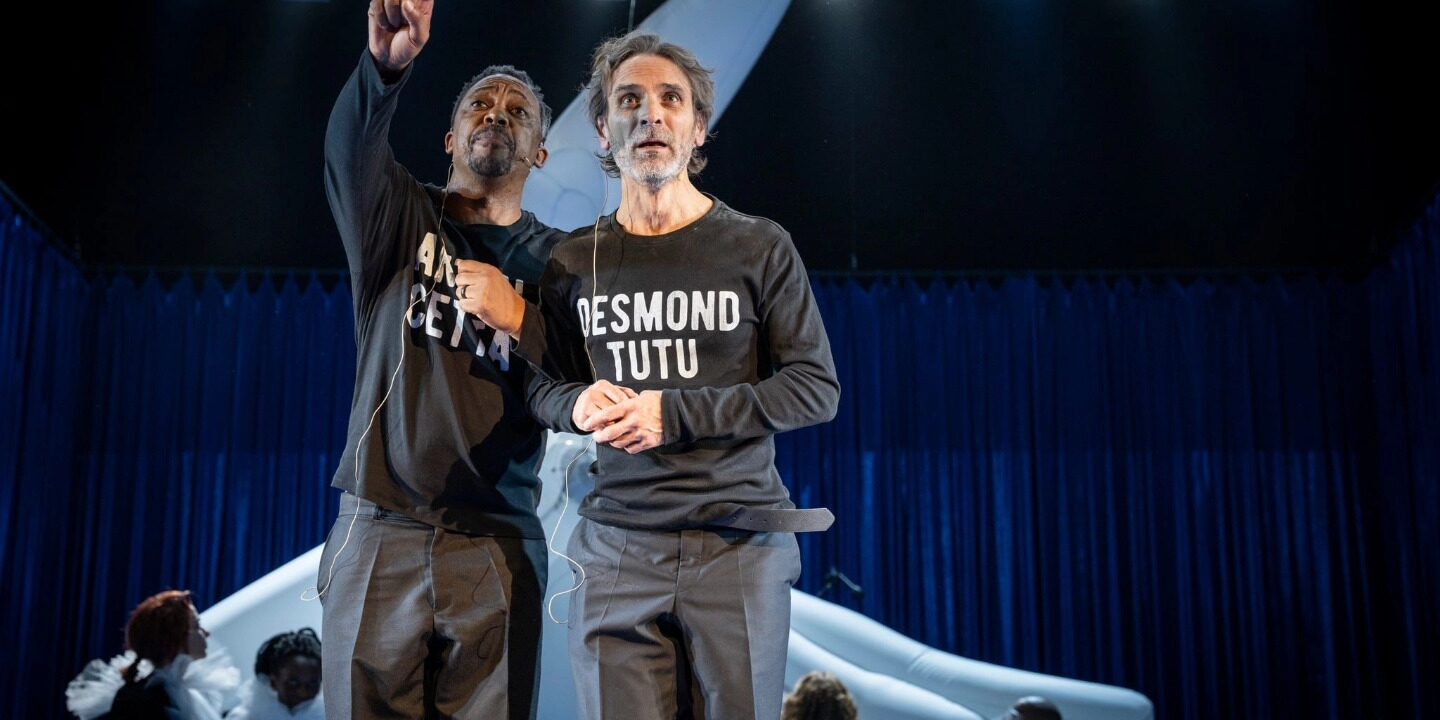

A final scene features Bishop Desmond Tutu (Arben Bajraktaraj) and Anton Çetta (Les Made) having a rendezvous in the afterlife. They agree to share their stories of struggle, but the encounter quickly escalates into a nonsensical bout about who gets to speak first. As they eventually calm down and make nice, an inflatable white dove rises in the background, bringing a sense of peace to the production. ‘It was worth seeing hands being shaken’, they tell each-other at the end.

Theun Mosk’s design includes a translucent screen onto which the actors’ faces are captured from various angles, showcasing their emotions. Images of Kosovo and South Africa, two countries from different hemispheres with similar pasts are also projected on the screen.

The cast, who come from Albania, Kosovo, and South Africa, work well together. Ema Andrea brings a beautiful agility to all the characters she plays. The versatile and experienced Ilire Vinca shines bright even in her dark roles. Gontse Ntshegang, who switches effortlessly between acting and singing, is capable of setting the stage ablaze and quelling fire. Kensiwe Tshabalala shapeshifts into a fierce Amazon, unapologetic and invincible. Arben Bajraktaraj displays quiet confidence, his performance gradually building in momentum. Les Made is a smooth presence throughout, his tone determined, his stance unwavering.

Jeton Nezirajj and director Blerta Neziraj are not afraid to work recurring themes into their art. They have often used the stage as a platform for remembrance and reflection. The scenes of the actors breaking character to eat pizza is a great directorial intervention. Working in collaboration with dramaturg Greg Homann, the line between truth and fiction is repeatedly called into question. There are moments, however, when the visuals in the background threaten to disrupt the flow of monologues, but at the same time the cast is to be commended for their expressiveness and physicality. Ntshegang’s face during her song of pain is an image that stays with you.

Despite reconciliation being the keyword, the play feels more like a sensory experience than a reconciliatory one. It conveys an urgency of detachment as an antidote to the unbearable weight of forgiveness – a near impossible feat for those who suffer deep loss and heavy shame.

“There was a big tree in the yard of my house… it cast a large shade…”, one character says at the start, an image symbolic of the long shadow cast by these atrocities. The words of Bajraktaraj’s character ‘Cannot forget! Cannot forgive!’ still echo; ultimately, he only forgives. The play feels like a game of ‘truth or care’ in the 21st century, which is swarming in flexible realities.

Regardless of truth, we still care.

Credits:

Author: Jeton Neziraj (Kosovo)| Directed by: Blerta Neziraj (Kosovo) | Dramaturg: Greg Homann (South Africa)|Performers: Ema Andrea, Gontse Ntshegang, Ilire Vinca, Kensiwe Tshabalala, Arben Bajraktaraj, Les Made

Composer: Bongile Gorata Lecoge-Zulu // Stage Designer: Theun Mosk | Ruimtetijd // Choreographer: Jochen Roller // Costume Designer: Blagoj Micevski // Video: Besim Ugzmajli // Lighting Design: Vincent Longuemare // Artistic Advisers: Agron Demi, Julia Wissert, Tom Mustroph, Catherine Kennedy, Riza Krasniqi //Lights: Mursel Bekteshi // Sound: Bujar Bekteshi // Coordination: Flaka Rrustemi

Producers: Qendra Multimedia – Prishtina, The Market Theatre – Johannesburg, São Luiz Teatro Municipal – Lisbon, Teatro Della Pergola – Florence, Theater Dortmund – Dortmund, Black Box teater – Oslo, Mittelfest – Cividale del Friuli, Théâtre de la Ville – Paris

For further information, visit: Qendra.org

Further reading: Under the Shade of a Tree I Sat and Wept: The search for reconciliation

Bora Shpuza is a literary translator and freelance art reviewer based in Prishtina,