Novi Sad Theatre, premiere 11th October 2025

“Nostalgia is a feeling I associate with a specific time: in late childhood, in that sensitive adolescent age, we see before us an infinite number of paths, and a few years later, when our choices narrow them down to just one, we begin to long for the time when we could choose among a great many different possibilities. That, to me, is nostalgia.” (Me’med, red kerchief and snowflake, by Semezdin Mehmedinović)

In Chekhov’s play, sisters Olga, Masha, and Irina wait for a bright future while nostalgically recalling a time when they could still choose their own paths, those good old days (or the times we remember as such). This idealised recollection and romanticising of the past, when they lived in Moscow, while they now wait to go to Moscow and begin a better life, this state of anxiety, hopelessness, and longing, imagining the future as a glorious past, has been transposed by the director into the very concept of the production.

Chekhov’s drama here unfolds in reverse, so we first see the final act, then the third, the second, and finally the beginning, where it becomes clear that the yearning for Moscow was futile from the start. The entire meaning of Chekhov’s play is contained in Olga’s final monologue (which in this production appears at the beginning), where she says she feels that soon they will find out why we live and why we suffer. “If only we could know that, if only we could know!” The rationalisation of suffering would free them from the desire to escape or relocate into something else. That is why the inversion of time works so well in this case. They are trying to understand, remember, and bridge the vast gap between life’s expectations and their reality. However, even a painful insight into the reasons for our suffering will not necessarily change things or bring the sisters to Moscow. The theme of nostalgia, central to the director’s interpretation, shifts from the individual to the collective. In our contemporary society, Botond Nagy detects this nostalgia in the irrational longing for Yugoslavia. Yugo-nostalgia is rarely questioned. In the play, the country that no longer exists is evoked through the raising of a flag and the set design of the final (that is, in Chekhov’s play, the first) act, when Irina celebrates her name day by a swimming pool decorated with Yugoslav flags.

Three Sisters, Novi Sad Theatre

It is said that the ancient Greeks believed a work of art can only be created if excessive depth is not pursued for its own sake. Applied to this production of Three Sisters, it means that Chekhov remains Chekhov, not because he is a classic or part of the dramatic canon, but because his work still resonates with the modern individual who feels trapped in a stagnant society. The director also explores Chekhov’s inherent fear that life is happening somewhere else and that it is being lived by someone else. In this performance, new monologues have been added that reveal not only the sense that life exists elsewhere, in Moscow, or that it once existed in the past, but also, through Natasha (a vivid and full-of-life performance by Gabrijela Crnković), the realisation that her very identity lies outside her present existence. Motherhood, she tells us, has made her devote herself entirely to her child, and in doing so, she has forgotten herself.

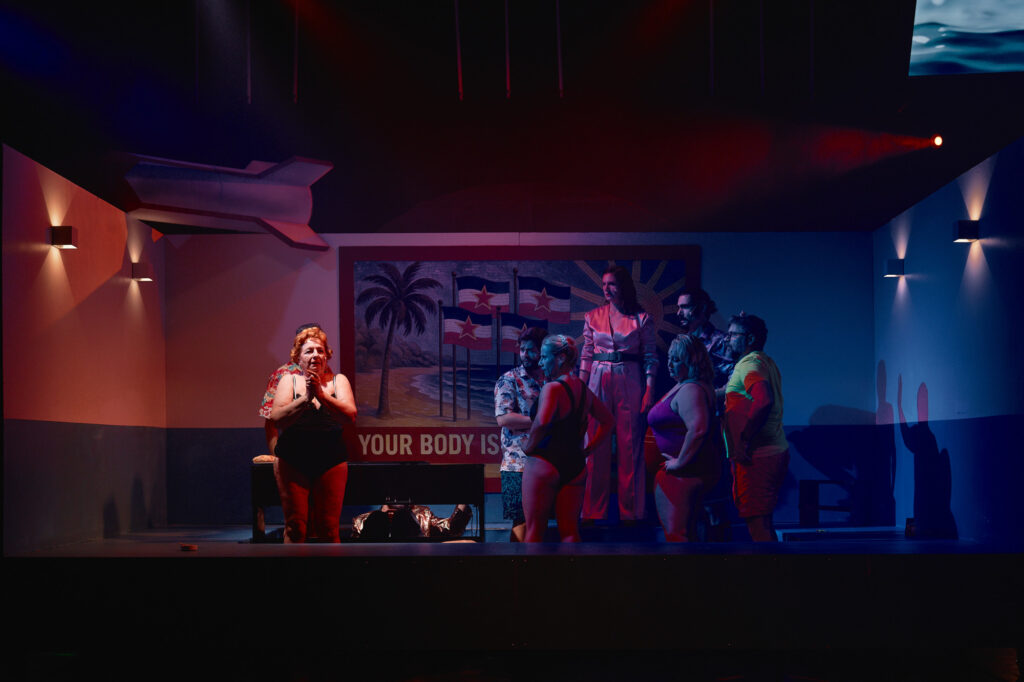

The most visually striking moment comes in the interlude, when Vershinin (a brilliant Gábor Pongó) transforms from a man with a disability into a dictator. At the same time, we hear Umberto Eco’s Fourteen Features of Fascism read in voiceover. Overall, the production abounds in stunning, almost surreal imagery, thanks largely to the outstanding lighting design and the scenography that changes with each act. From the aeroplane cabin where the sisters “fly” to Moscow (a destination they never reach), to the swimming pool marked with the words Your body is a battleground (the famous 1989 artwork by Barbara Kruger that became an iconic feminist and pro-choice statement).

That single scene, three sisters in swimsuits celebrating a name day, Yugoslav flags behind them symbolising a country that fell apart in war, as they talk about a war that had happened, while several wars rage across word today, and behind them the reminder that the female body is a battleground, illustrates how every fragment of this production can be unravelled and interpreted. Many such moments flash by too quickly, or slip past us unnoticed, simply because of the piece’s density and the sheer amount of action to follow.

The acting style also leans, in a sense, toward exaggeration. What remains from Chekhov are the slow-paced scenes, long meaningful monologues, and extended pauses, all underscored in every moment by the repetitive soundscape of the space. Masha, who in Chekhov is melancholic, impulsive, dissatisfied, torn, and ill-adjusted, is here transformed by Judit László into a character bursting with vitality and audacity, winning us over with humour rather than wistfulness. Lívia Banka’s portrayal of Olga illustrates the life journey of an intellectual woman in the provinces. She plays the role solidly, without unnecessary pathos, while subtly highlighting her bitterness. Terézia Figura brings to Irina a beautiful lightness we are perhaps not used to seeing in productions of this play. Traditionally portrayed as the greatest casualty of transition, Irina manages to retain her optimism. Gábor Mészáros appears for the first time in nearly two decades on the stage of the Novi Sad Theatre as Andrei, the brother full of potential, yet lazy, passive, and ineffectual. He is highly expressive, emphasising his alienation without making it uncomfortable or painful to watch.

Three Sisters, Novi Sad Theatre

In this version, Andrei aspires to be a successful film director; however, we witness his dream’s downfall, transforming him from a promising young man to one crushed by his father’s ideals. On stage, he films small facial expressions with a handheld camera, adding a visual layer to the performance’s aesthetic, which flirts with eclecticism, maximalism, and the blending of different media, including theatrical and musical genres, ranging from Kylie Minogue and Desireless to Zdravko Čolić, a Serbian cover of Madonna, and the Yugoslav band Haustor. In short, there is everything in this production!

The performance concludes with the song Ne lomite mi bagrenje (Don’t Break My Locust Trees) by Đorđe Balašević. This song is often played at student and civic protests, particularly for the line Da je bilo sve po zakonu (If everything had been according to the law). The moment that lyric rang out, a sharp sound effect of something collapsing echoed through the space, instantly evoking the fall of the canopy in Novi Sad. In that moment, it felt as though this city, and all of us, were, like Olga, Masha, and Irina, longing for a better future, aware that we and Novi Sad cannot return to the time before the canopy’s fall.

After the show, one woman in the audience exclaimed: “I didn’t understand a thing.” Some acting students who performed the play Three Sisters last year and are very familiar with it shared their feelings of confusion and amazement after the performance. Both reactions make sense. The audience may feel puzzled by the disorienting dialogue and actions, but they will constantly feel the thrill of the theatrical act. If this performance were a painting from art history, it would be a work by Hieronymus Bosch, simply because we admire it, yet we don’t always know what’s happening. If you are familiar with Chekhov (the same goes with Bosch and his art), you will have a basic understanding of the performance; however, this may not greatly assist you in grasping all the details. If you, on the other hand, come without any prior knowledge, you’ll still enjoy yourself. You just have to remember that theatre is, above all, a game.

Author: Anton Chekhov, Botond Nagy // Director: Botond Nagy // Dramaturgy: Kali Ágnes // Light Design: Cristian Niculescu // Composer and video design: Claudiu Urse // Set: Theodor Cristian Niculae // Costume designer: Ioana Ungureanu

Cast: Banka Lívia, László Judit, Figura Terézia, Mészáros Gábor, Pongó Gábor, Kőrösi István, Szalai Bence, Crnković Gabriella, Német Attila, Bíró Alekszandra, Aljoša Tasovac

For more information on Novi Sad Theatre, visit: ujvideki.com

Divna Stojanov is a dramaturg and playwright. She writes mainly for children and young people.