Belgrade Drama Theatre, premiere 25th June 2023 (Grad Teatar Budva)

In 1771, in a well-known speech given by Goethe on the occasion of Shakespeare’s Day, there is a sentence that says little about Shakespeare’s plays, but much more about Goethe’s understanding of drama: All of Shakespeare’s plays revolve around a hidden point (…) in which what is characteristic of ourself, the freedom to which our will aspires, collides with the inevitable course of the whole. The explosive collision of the earthly and otherworldly worlds, and Faust, a poetic figure typical of the 18th century, an intellectual who seeks to understand the absolute truth about man and nature through science and later love, is refracted through Goethe’s drama Faust. The writer worked for a total of six decades. When he finished, he wrote: I look upon the rest of my life as a gift.

The Belgrade Drama Theatre production of (Pra)Faust, directed by Boris Liješević was performed at the Grad Theater Budva festival, in the amphitheatre of the Holy Trinity Monastery in Stanjevići, on a chilly August evening. In the adaptation, the Liješević selected the points of Faust’s journey necessary for understanding his story.

Although the title suggests that the first version of the play Pra-Faust was taken as the basis of the performance (preserved as a manuscript transcription made by an unknown woman in court and found in her legacy), the play’s text is based on the play Faust with a few notes about the differences between the versions. For example, before a humorous scene in which Mephistopheles fears the church and God, the actors note that it is not present in the later version of the text.

The most significant change occurs at the very end of the drama. In Pra-Faust, the tragedy is complete. There is no response to Mephistopheles’ words directed at Gretchen, “She is condemned.” In Faust, however, a Voice from above shouts that she is saved. The fourth wall is also successfully and humorously broken in the scene where Faust talks to the Spirit. An audience member is given the Spirit’s text on a piece of paper. Engaging the audience in this manner is characteristic of Liješević’s work, (he also assigned a part of the text to the viewer in his performance of The Magician).

This core work of European literature and theatre is often staged sensationally. Liješević, very cleverly, chooses the opposite approach and places the action on an empty stage with a piano and a few chairs, indicating the playing space (which only Mephistopheles crosses) with a floor on which faintly visible praying hands are painted. Next to it is a stand on which Mephistopheles’ costumes hang. He changes into them throughout the show, because, as we know, the devil has a hundred faces: there are red jackets, contemporary and old fashioned clothing, (for the devil is timeless), bright red sneakers, scarves and wigs and an umbrella with the Rolling Stones logo on it. At a semantic level, it remains unclear why this band and later, at Mephistopheles’ party, where their song “Sympathy for the Devil” plays in the background, are devilish symbols.

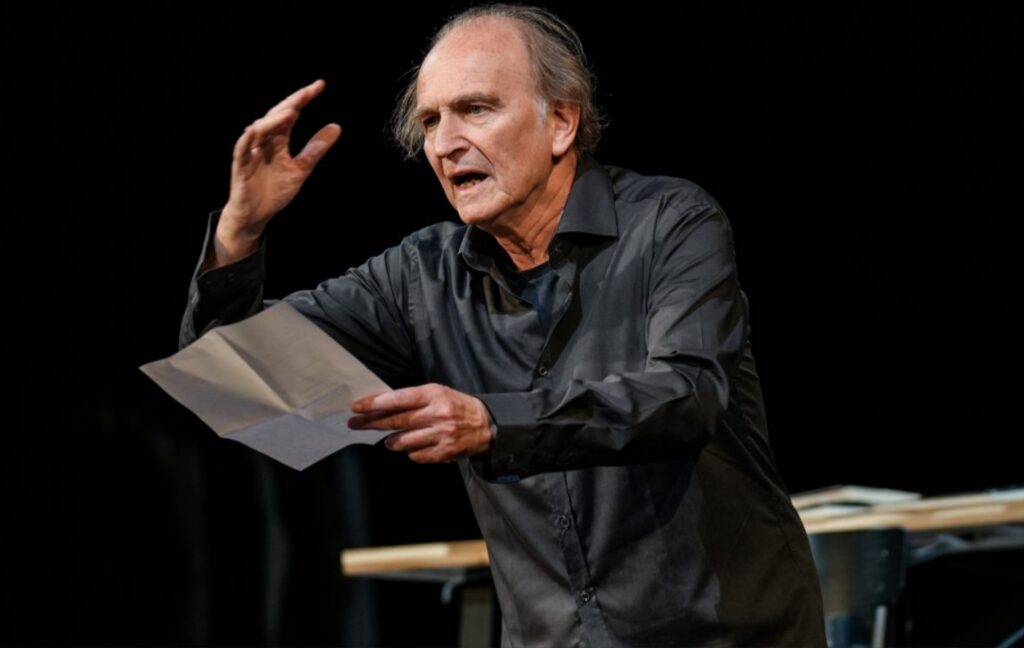

Svetozar Cvetković in (Pra) Faust

Ozren Grabarić makes the character of Mephistopheles not just a principle of evil and an antagonistic force, but a lively, seductive, ironic, and witty presence, entertaining in his nihilism. Grabarić authentically expresses Mephistopheles’ madness, joviality, playfulness, unpredictability, and constant variability in expression and style, especially through his facial expressions. In his interactions with Faust, we can see the strong contrast between the two principles and characters.

Unlike Mephistopheles, Faust is educated and intelligent, but passive, isolated, in a deep existential crisis, pondering the meaning of life. In his interpretation, Svetozar Cvetković creates just such a character, a man who seems restrained by reality, rushing and enclosing himself in dogmas, knowledge, and verses, and to whom Mephistopheles’ lively spirit might even be tedious. Along the way, they encounter students, local drunks, a waitress, and the unenlightened sanctuary (portrayed in brilliant episodes by Ivan Tomić, Daniel Sič, Ivan Zarić, and Stanislava Nikolić).

As Gretchen, the excellent Iva Ilinčić captivates with the ease with which she immerses the audience into the oppressive and unenlightened world of the lower bourgeois layers. After Faust and Mephistopheles’ journey, she opens the door to her God-fearing mother, the prying and opportunistic neighbour in the small town (a fantastic and witty performance by Mirjana Karanović), gossipy friends, a society that throws stones at the fallen Gretchen instead of showing empathy towards a young woman who is suffering, instead of helping her.

Without unnecessary psychological dissection, artificiality, and pathos, Ilinčić creates a naive and inexperienced Gretchen who, with her faith and sincerity, is an equal match for Faust. Her final scene is particularly touching and poignant. Imprisoned, she speaks to Faust about infanticide and rejects freedom. Ilinčić convincingly transforms from a love-struck girl intoxicated with longing, to a woman plagued by doubts, to a shell of a woman, deathly afraid and ready for death, playing each version with equal authenticity.

Gretchen’s tragedy plunges Faust into the deepest despair, but he and his desires remain unchanged. Faust continues to wreak havoc and inflict pain, true to his goal and himself. The subtitle of Faust reads: Tragedy – and it can be applied to Gretchen’s fate, but even more so to Faust’s life journey. Therefore, the ending of the show becomes somewhat disorienting. Cvetković asks us: considering God has already saved Gretchen, can we forgive her sins?

In this way, the focus and essence of the story, from the source of the destructive force of evil, are shifted at the end on to Gretchen’s fate, or rather, to the consequence of that force. The question also appears quite banal. It felt as if we had been watching a story exclusively about petty bourgeois life all along. As if the play’s attempts to highlight that the action on stage can also be mirrored in our reality, in our judgmental society. The entire story of Faust – Goethe’s symbol of alienated humanity, the man over whom God and the Devil wager, the play that had altered the spiritual climate of Germany and made it a few degrees warmer – is reduced to the question of whether we in the audience would forgive one woman.

Here is my answer to the question: yes, we can forgive Gretchen, but it is harder to forgive the director and his team for this final line, and what it does to an otherwise strong performance.

Credits:

Director: Boris Liješević// Dramaturg: Fedor Šili// Translation: Branimir Živojinović

Costume Designer: Marina Sremac // Composers: Stefan Ćirić, David Klem // Choreography and Stage Movement: Sonja Vukićević // Speech and Diction Coach: Dr. Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Cast: Svetozar Cvetković, Ozren Grabarić, Iva Ilinčić, Mirjana Karanović, Ivan Tomić, Daniel Sič, Ivan Zarić, Stanislava Nikolić

For tickets and further information, visit: BDP.rs

Divna Stojanov is a dramaturg and playwright. She writes mainly for children and young people.