Historical Museum of Serbia/National Theatre Belgrade, 26th September 2022 (part of BITEF)

With its focus on labour and working lives, it is not surprising that the 56th edition of BITEF contains several examples of documentary theatre. Two contrasting pieces, Gardien Party and Tijuana, from France and Mexico respectively, were performed on the same night.

Gardien Party, created by playwright and theatre director, Mohamed El Khatib, and writer and visual artist Valérie Mréjen, for French company Zirlib, draws on the lives of the piece’s co-creators and performers, a group of museum and gallery attendants around the world and is designed to be performed in museum spaces. In this case, it was performed in the Historical Museum of Serbia.

Five museum attendants, from Paris, St Petersburg, Stockholm and two from New York, describe their working lives. Their job is to sit among the artworks and objects and keep an eye on the visitors, to be spectators and a place where people come to look. They are there to ensure the rules are respected. They are meant to keep interaction to a minimum. They are not there to educate or provide an opinion on the art, but rather just to ensure that the visitors don’t give into the impulse to touch the art works, that their children don’t turn cartwheels next to the priceless artefacts, and to point people in the direction of toilets. They are not supposed to read or listen to music. They are just supposed to sit there and observe, something that, in the words of one attendant, requires them to master the art of being present and absent at the same time.

This particular mixture of visibility and invisibility is something we ask of many people in the service industry, in retail, in hospitality, to fade in and out of view as required. In the case of the museum attendants, they are supposed to be still and silent, to be like statues, though in their case the idea is to deflect the gaze of the visitors not to attract it. (The Netflix crime drama Lupin made good use of this paradox, with the master thief using the public’s selective blindness to help him to pull off a jewel heist).

The attendants describe the different factors that drew them to the job. For some it is the prospect of comfortable, sedentary regular work as they near retirement age, for others it is a stop-gap while they are studying, a stepping-stone job. The French attendant seems slightly bitter about his situation, being overqualified and forced to take work that is at least vaguely related to his field of art history in the wake of a messy separation.

They share stories of subtly bending the regulations. The Swedish guardian finds the imposed stillness frustrating and does exercises on the sly. The young Japanese woman working in a New York gallery uses her hair to hide her headphones as she surreptitiously listens to music. Some find the uniforms an annoyance, others a helpful way of compartmentalising their lives (nobody likes the unnerving art-inspired facemasks they wore during the height of the pandemic). The Russian guard – performed by Nathalie Conio Vavilova – is the funniest of the five, doing her knitting and eating chocolates. The New Yorker, performed by Boney Fields, is affable and charismatic

The dramaturgy of the piece is relatively straightforward and static until a sixth attendant appears in a pleasing coda. He works the night shift and, in the absence of visitors he gets to interact with the art and the space in a different way to his daytime colleagues, as a former ballet dancer he gets to dance amid the art when no one is looking (a nod, perhaps, to the gallery scene in Godard’s Band a part and a way of highlighting the often reverential manner we move through spaces devoted to the display of art).

At one point the guards talk about their favourite artworks and proceed to tape posters of them onto the walls, but this is not really a show about art rather about the tacit pacts we make with people who work in these roles (a similarly illuminating piece could easily be made by theatre ushers), about our ability to look at and look through people depending on their job and status, on the uniform they wear, to queue for two hours to gaze upon the Mona Lisa – and then take a photo of it – but choose not to see, or not to see in the same way, the people standing next to it.

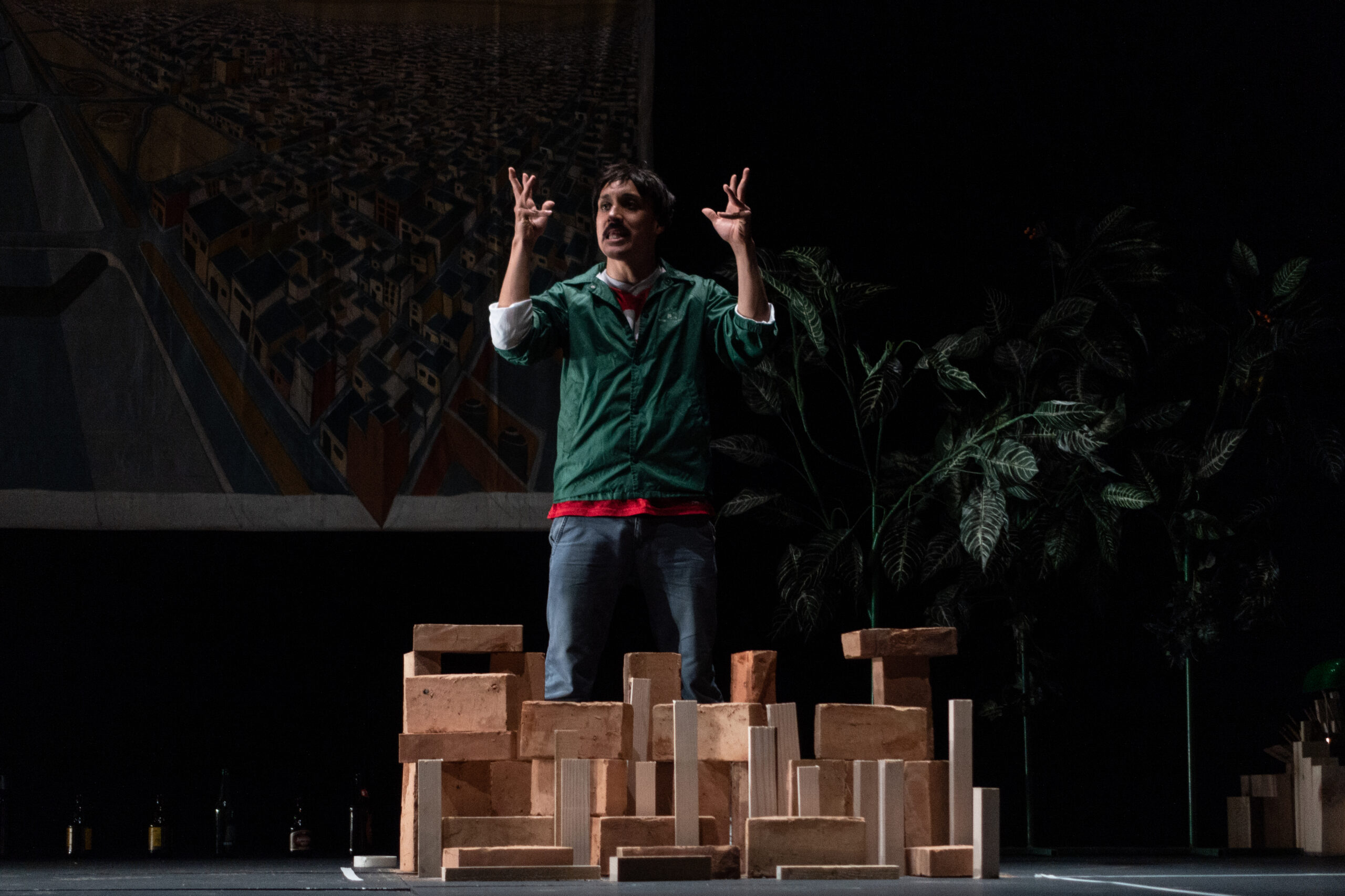

Tijuana. Photo: Jelena Jankovic

Tijuana, a piece of documentary theatre co-produced by Lagartijas Tiradas al Sol and Festival Escenas do Cambio, Santiago de Compostela, also explores working life, but through a very different lens.

Mexican actor Lázaro Gabino Rodriguez sets out to explore what kind of life it is possible to live on Mexico’s minimum wage. In law, this minimum wage – which equates to around 1 euro a day – is supposed to be enough to get by on, but, in reality, people are often forced to work long hours and multiple jobs in poor conditions to survive. The existence of this minimum wage legitimises a culture of precarious and often dangerous and illegal working conditions. Rodriguez sets out to investigate this by living on minimum wage himself for month. Well-known as an actor, he disguises himself with an unflattering moustache and moves to Tijuana where he acquires a factory job and finds a place to love in a ’colonia’, a makeshift neighbourhood, sharing a cramped apartment with another family.

He documents this experience in diaries which he uses to shape this show – allowing him to recount his experiences as they felt to him at the time – and makes covert videos. Rodriguez talks us through his experiences, mapping out his accommodation on the floor in tape and building a miniature colonia out of house-bricks. On a small screen we see jittery video footage, images of his diaries and an interview with him reflecting on the experiment.

The project brings to mind Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed in which the journalist went undercover to investigate the impact of the 1996 welfare reform act on the working poor in the United States, by taking cheap lodgings and working as a waitress and a care worker.

Rodriguez recounts the monotony of his packing job, the pleasure of the single cigarette he can afford a day, and the release of the weekly visit to a nightclub. He is an engaging narrator, capable or constructing characters through gesture and voice, but there are moments in which the piece lacks dramaturgical and journalistic rigour. It describes life within the colonia in detail, the status of people within the different sectors and the self-governing nature of the community as well as an act of sickeningly violent retribution against a man accused of rape, an incident that makes Rodriguez terminate his experiment early, but it does little to contextualise these things.

In other moments the piece lacks ethical clarity – for example, when he encounters the teenage daughter of the family with whom he is cohabiting, naked in the bathroom, and worries not for her and how she might feel, but about impregnating her and becoming stuck in this life for good. This might honestly reflect what he thought at the time, but it is uncomfortable nonetheless.

That is not to say that Tijuana lacks self-interrogation. A banner hangs over the stage declaring “The Truth is also an invention”, and Rodriguez acknowledges that he is involved in a fundamentally deceptive exercise, that he can leave this life whenever he chooses, that the stakes for him are different and that even a performance rooted in documentary practice is still a performance. Rodriguez eventually comes to question his aims in undertaking this project, to question what need in him it met, but in doing so Tijuana comes to feel as much a test of himself as an actor and a man as it is an investigation into exploitative practices.

Both pieces uses documentary theatre techniques to reflect the lived experiences of working people. In concerning itself with precarity of the low-waged, Tijuana is a fiercely relevant piece of art, concerned with fundamental human questions, but of the two shows, the more whimsical, gentle Gardien Party is the more theatrically satisfying piece.

Main image: Gardien Party Photo: Jelena Jankovic

For further information, visit: bitef.festival.rs

Further reading: Dr Auslander (Made for Germany): Documenting migrant stories at BITEF

Natasha Tripney is a writer, editor and critic based in London and Belgrade. She is the international editor for The Stage, the newspaper of the UK theatre industry. In 2011, she co-founded Exeunt, an online theatre magazine, which she edited until 2016. She is a contributor to the Guardian, Evening Standard, the BBC, Tortoise and Kosovo 2.0