Glej Theatre, Ljubljana, premiere 2nd December 2025

Since Ted Kaczynski aka the Unabomber published his manifesto in 1995 in the Washington Post, many young people have begun to follow his ideas, Anarchist publishers in almost every country have on their shelves a printed copy of his text Industrial Society and Its Future. The text has sparked numerous controversies due to the author’s radical approach to technology, which, according to Kaczynski, is destroying society.

Probably not only I, but many young people went through a youthful fascination with him, searching in his writings for answers to questions about the truth of the world. Over time, however, my enthusiasm, like that of my friends, waned as we began to notice the ideological shortcomings of the manifesto. This does not change the fact that the text still attracts great interest – perhaps especially now, in a time when the bubble surrounding AI continues to grow and the most powerful people in the world are becoming infatuated with the topic.

An attempt to understand Ted Kaczynski himself, along with his philosophy, has now also been undertaken by the theatre with the premiere of A Manifesto, a co-production of the Glej Theatre and the Mladinsko Theatre. The performance was created as part of a two-year project in which the Glej Theatre explores the relationship between technology, society, and the individual. Such a programme could not omit Kaczynski. A Manifesto is a performance about the protagonist and his philosophy, and at the same time an attempt at the creators’ own analysis of that philosophy and a search for meaning in a text from the previous century that may still hold relevance in the 21st century. It touches on technological progress and left-wing values – topics that Kaczynski himself dealt with.

The performance is a small-form production. In contrast to the radical text that inspired it, the theatrical form remains relatively traditional and minimalist. Its greatest value lies in the text itself and the process of its creation, along with numerous references to other authors such as Dostoevsky and Kundera. The dramatic text was created mainly on the basis of the manifesto itself and other writings by Kaczynski concerning his life. An interesting dramaturgical device is the inclusion of AI in the work on the play, whose lines appear in one of the most intriguing scenes of the performance.

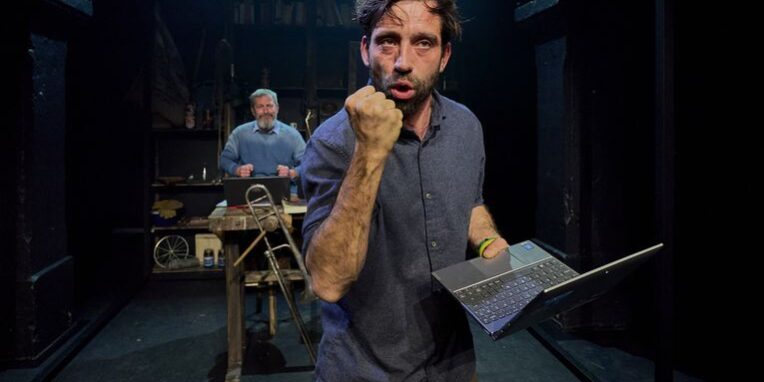

A Manifesto is based on a simple formula involving the constant shifting of narration and characters between the two actors – Željko Hrs and Vito Weis. At times, they play themselves – actors creating a performance about Kaczynski and technology, and at other times, they play Kaczynski himself. The character of Kaczynski is divided into two versions: Teodor and Teo, with one of them subjected to experiments at the university, which corresponds to facts from the protagonist’s biography. The actors’ characters talk about the present, about replacing actors with technology, about the power of photomontage, while the Ted characters talk about his philosophy. Who is speaking at a given moment can be understood from context, acting, and the characters’ positions on stage. The structure of the performance conditions the viewer to understand that a change in a character’s position in the stage space signals a change in narration.

A Manifesto. Photo: David Oresic

The set design by Damir Leventić imitates the small cabin in which Ted Kaczynski lived and constructed his bombs far from civilization. The stage is therefore limited mainly to representing this space, which gives the actors relatively little room for choreography. Most scenes take place at the table where the actors mimic the construction of a bomb. Behind them is a large shelf with various tools, as well as a screen on which images or texts are occasionally displayed from the beginning of the performance. The costumes are simple and reference Kaczynski’s appearance. Both actors wear similar outfits, emphasizing that they both embody the role of the Unabomber. One of the most interesting elements of the performance is the live music created by two trombonists: Lenart Maček and Črt Pačnik. The instrument is a reference to Ted’s biography, as he was an amateur trombonist and even played in prison. The music opens and closes the performance and also serves to disrupt certain scenes, introducing an additional dramaturgical dimension.

A Manifesto opens with a scene generated by AI. On a small television screen appears a recording of Ted Kaczynski that looks exactly like the well-known prison interview circulating online. This time, however, Kaczynski refers to the performance. The altered questions and answers imitate reality while introducing the viewer to the interrogated character. At the end, Ted says: “Good luck with the performance.” It is a strong and intriguing opening. Unfortunately, AI does not appear as often later on, and the reflections on its impact are based on basic and superficial observations. Further reflections on Kaczynski’s life and on technology intertwine, which may raise the question: should the emphasis fall on the figure of the Unabomber or on the dangers associated with technological development? While Ted’s character is presented rather skilfully, the technological threads remain more in the realm of loose reflections. The performance therefore does not provide a clear answer as to whether Kaczynski was right or not; rather, it leaves the audience with clues they may continue to follow. Perhaps it is precisely this lack of radicalism on the part of the creators that becomes evident against the backdrop of Kaczynski’s own radicalism.

Personally, I also regret the lack of radicalism in the very use of technology in the theatre, which is becoming increasingly present on stage. The Rimini Protokoll group – a German independent collective – has been exploring such solutions for years, and not only in performances devoted to technological themes. Meanwhile, the subject chosen by the creators – an extremely radical figure and an anarchist ideology – ultimately fades within a rather classical performance. Perhaps a more interesting solution would have been to create a production that reject technology completely, following the model of Kaczynski’s life choices, or is based entirely on new technologies?

The most interesting moment of A Manifesto is the scene in which Željko and Vito are tasked with writing a monologue about freedom and decide to create it with the help of artificial intelligence, one using ChatGPT, the other using DeepSeek. The result turns out to be comical. The AI generates pompous, overly emotional, traditionally structured monologues that would hardly win the approval of contemporary dramaturgical critics. The actors perform them just as humorously, emphasizing the artificiality and awkwardness of the generated texts. This scene can be contrasted with an earlier dialogue in which Vito admits he is afraid of being replaced by technology. Yet the monologues created by AI show that such a scenario seems rather unlikely. It is also worth noting that the very idea of theatre collaborating with machines is nothing new. As early as the Italian futurists, Prampolini and others dreamed of theatrical experiments with automation.

In addition to ChatGPT and the modified recording of Kaczynski, the performance also features VR glasses worn by Vito. On the screen, an animation is displayed intended to represent what is happening in the virtual world. However, this scene is less effective because it is the actor, not the audience, who experiences the virtual reality. It is precisely the inclusion of the audience in theatre using the latest technologies that allows them to feel its immersive nature. As a result, we are left with just another animation, perceived like any other media insert used in theatre. Here, technology neither creates a real impression nor enhances the message, and arguments for or against it lose their impact. Consequently, the performance serves well as a tool for conveying Kaczynski’s story, but is less effective as a vehicle for conducting complex and nuanced reflections on technological progress.

Credits:

Karolina Bugajak is a theater critic from Poland, currently living in Ljubljana. She studied culture and contemporary art at the University of Lodz. The title of her master's thesis was "Theatricality and Exaggeration. Camp aesthetics as a strategy for creating new identities in the plays of Grzegorz Jaremko". Her main theatrical interests include topics such as institutional criticism, the representation of marginalized groups in plays, and most recently the theater of the former Yugoslav states.